by Mohamed Shafeeq Karinkurayil

“Shadow Craft: Visual Aesthetics of Black and White Hindi Cinema” (Bloomsbury 2020) authored by Gayathri Prabhu and Nikhil Govind sets out to study the black and white Hindi cinema between 1947, when India became politically independent, and the early 1960s when colour was established as the dominant mode of cinema. The authors' wager is that black and white is not to be studied as the lack of colour or as a moment in the evolution towards – to borrow from Andre Bazin's words on sound cinema – the fulfilment of the Old Testament of cinema. Rather, black and white could be understood to be structured in its own right, with its grammar realized in enunciations.

Buy This Title

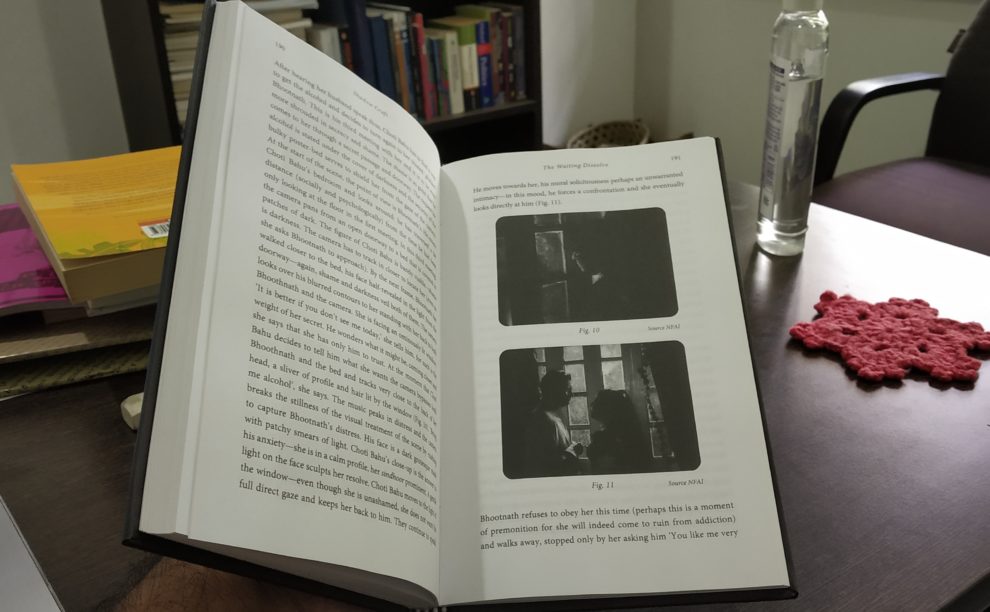

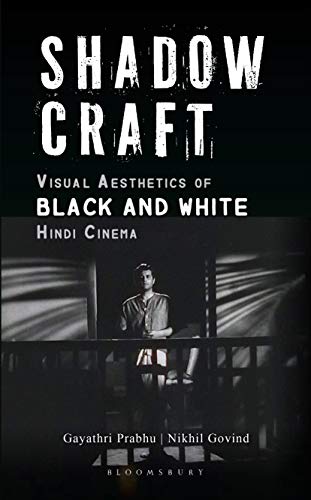

The book pays rich attention to select scenes from some of iconic black and white films of the period under discussion age – “Aag” (1948), “Mahal” (1949), “Pyasa” (1957), “Sujata” (1959), “Sahib Bibi aur Ghulam” (1962), and “Bandini” (1963), to put them in chronological order.The authors illustrate how a fidelity to image can upset some of the common senses about the films under discussion. An example of this is how the authors complicate the given truth of “Mahal” being a gothic with elaborate attention to what is happening on the screen.

The recent years have seen an explosion in the field of film studies in various directions. The dominant trend in South Asian film studies in recent years has been to stress the embodied reception of cinema while also paying attention to the text of the film. This modus has entailed an ethnographic engagement with the film cultures in South Asia, at the level of production, circulation and consumption. Some of these works have also paid attention to the affective resonances of the filmic text. “Shadow Craft” pulls us back into the frame of the films and makes us ponder over the affective surface it lays before our eyes, and coaxes us to see them with fresh eyes, as they might have been received in those hopeful immediate years of independence. In this, it demands that the reader too arrive unburdened by history. The authors' indulgent attention is paid to the diverse enchantments of the screen – the trope of the artist, the female portraiture, but also to motifs of the stage, and the overdeterminations of effect in the camera in the film (or the film within the film).

It is not easy to verbalise the visual, but the authors have kept at it. The book also provides rare and evocative images from the archives. The last chapter of the book, titled “Outro: Reel Number 13” stands out as the experience of the authors in their quest to find an elusive reel for this book, and makes a case for a systematic intervention in preserving our filmic link to a bygone era.