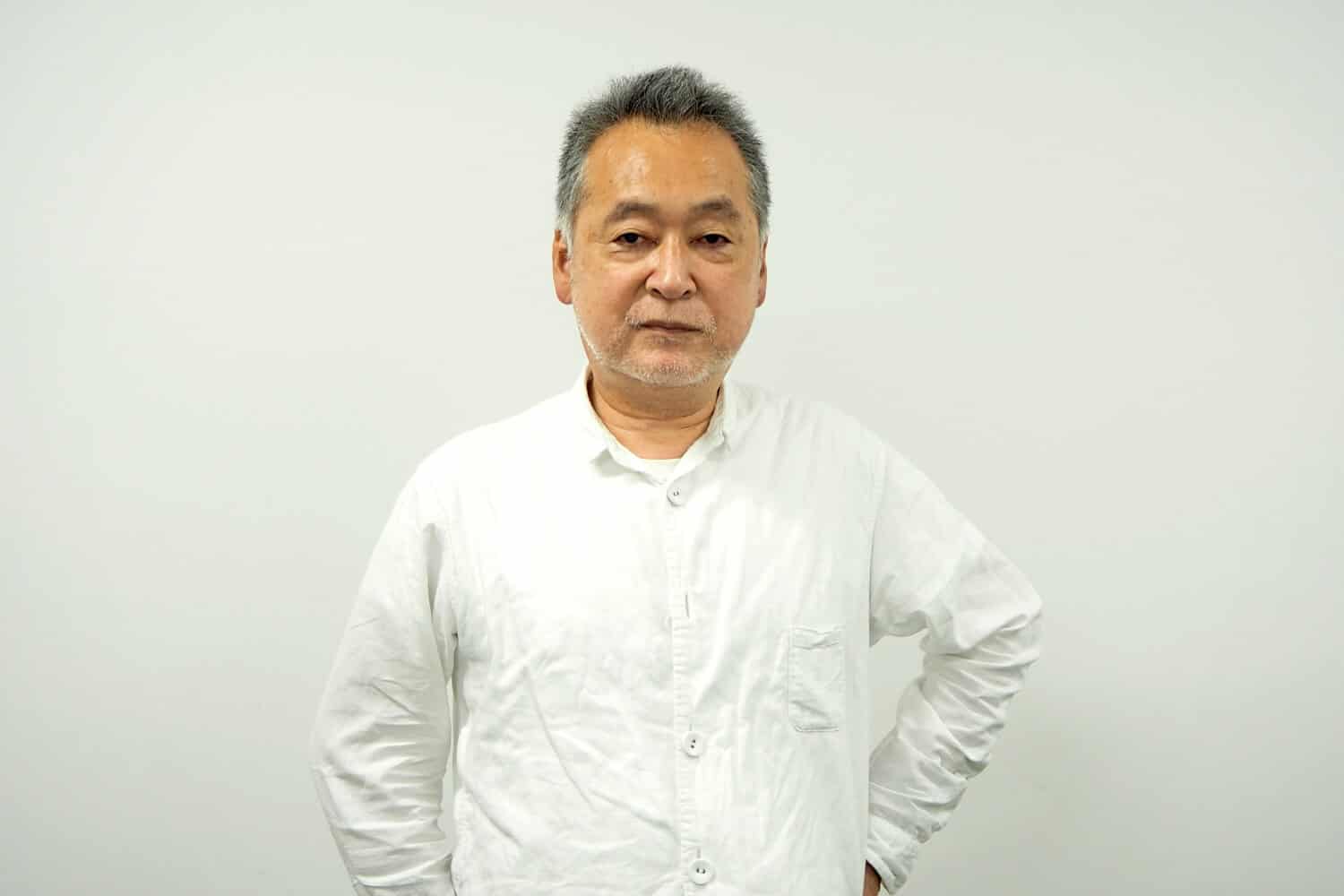

In an unprecedented choice for her, Miwa Nishikawa does not direct a script of her own, but adapts a novel, Ryuzo Saki's Naoki-winner “Mibuncho”, for her latest movie. Furthermore, she cast Koji Yakusho as her protagonist, proving once more, after “Dear Doctor” and Tsurube Shofukutei, how well she can cooperate with veteran actors.

“Under the Open Sky” is Screening at Five Flavours Asian Film Festival

Yakusho plays former yakuza, past middle age Mikami Madao, who has just been released from prison after a thirteen-year murder sentence. Mikami, an orphan, has spent all his life between working for the mafia and being in prison, but this time is set on turning a different page and finally becoming a “proper” citizen. However, being essentially illiterate and without any particular skill, he finds himself racing against all odds, including his own, short-tempered and violent nature. Tsunoda, a young ex-producer/current writer, is tasked by a TV producer to come up with a program focusing on Mikami, although the latter thinks that the purpose of the show is to help him find his mother. Lawyer Souji and his wife (played by the much missed Meiko Kaji) help him as much as they can, with the same applying to welfare officer Iguchi, while Mikami eventually befriends local supermarket manager Matsumoto, although their relationship begins in the bumpiest of ways. However, Mikami finds out how difficult it is to truly reform and become a member of a society that is quite prejudiced against ex-yakuza/convicts, and how unequipped his previous life has left him against even the smallest demand of modern living. A trip to some of his old comrades takes things into perspective, and his insistence along with the help of his friends are his main weapons in this, rather unfair fight.

Miwa Nishikawa directs a film that is, simultaneously, sensitive, realistic, pointy, funny and somewhat romantic, with her combining all the aforementioned elements in the most elaborate way. The realism comes from the way the current lives of the yakuza, and particularly of those who have managed to get old, is presented, with Mikami, but even more his former boss, highlighting this comment in the most realistic, but also dramatic fashion. The way society perceives these people, with others trying to exploit them (the producer) and others just being prejudiced against them (the supermarket owner in the beginning) adds to this comment. Furthermore, the fact that this perspective is even established by law comes as a true shock (members of yakuza or other anti-social groups are not allowed to get social benefits from the state, which is occasionally their only way to sustain themselves lawfully). Lastly, that the current Japanese society is one that has left very little space for rehabilitation also comes to the fore, as Mikami stumbles upon numerous obstacles, despite his intense efforts.

As the aforementioned is the main element of the narrative, the film could easily become a hard-core (melo)drama, but Nishikawa's steady hand does not allow it to his this reef. She accomplishes that by injecting a sense of hilarity in the story, that mostly derives from the yakuza-prison rules discipline that Mikami exhibits on a number of occasions, all of which are particularly funny. Nishikawa also uses humor to make another set of social comments, most of which are “hidden” in details with the two scenes involving mail ports in apartment doors being the most obvious sample of this approach. The second tool she uses is the presence of many people who want to help Mikami, and even more, are completely transformed by his attitude and efforts, with their presence actually helping in both the many episodes and in the progression of the story.

At the same time, however, one could say that this, rather romantic approach, somewhat strips realism from the movie, despite Nishikawa's obvious effort to leave a sense of optimism to the viewer. In that fashion, the social worker seems unlikely helpful and good, Tsunoda's metastrophe the same, while the easiness Mikami receives loans, money and in general help from people he barely knows also seems highly unrealistic. On the other hand, this aspect could be perceived as an effort to show the value of friendship, and how much people like Mikami need the help of others to survive.

The second fault, and one that has become so common in modern Japanese titles that is actually quite frustrating to witness, is that Nishikawa misses a number of perfect moments to conclude the film (I counted five), instead prolonging it for no apparent reason, reaching 126 minutes in a story that could have easily entailed all its essence in much less. This approach actually makes “Under the Open Sky” become somewhat tedious close to the end, although the actual finale somewhat compensates.

Koji Yakusho has been one the very top of Japanese actors for decades now, and he reaches one of his apogees here, in a rather demanding role that allows him to highlight his versatility and the sense of measure that characterizes his performance in the most eloquent way. Either angry, violent and frustrated or remorseful, pleading and sad or even simply happy, Yakusho is a pleasure to watch, in one of the best performances of his career.

Technically, the movie continues the quite high standards Nishikawa has gotten her audience used to. Norimichi Kasamatsu's cinematography captures the many different aspects of Japanese society with realism, while a couple of panoramic shots present images of extreme beauty, particularly the one of night–time Tokyo. The subtle music, with a couple of exceptions of fast jazz giving the rhythm, accompanies the narrative in the most fitting way. Tomomi Kikuchi and Ruji Miyajima's editing induces the film with a harmonic, relatively fast pace, although they could do with a bit more of trimming.

“Under the Open Sky” comes pretty close to becoming a masterpiece, and just misses the opportunity due a single and unfortunately quite frequent fault.