This second installment of Park Chan-wook's “Vengeance Trilogy” is the film that turned global interest toward Korean cinema, one that's a true masterpiece of South Korean cinema, and one that is still discussed for its unique aesthetics and elaborate technique. “Oldboy” screened at festivals all over the world winning tens of awards, with the Grand Prix at the 2004 Cannes Film Festival being among them. Please note that the article contains many spoilers.

Park's films have a unique and magnificent visual style. However, as he has stated, the technical part comes second in his movies, with the first role being reserved for the characters and the story. His process starts with the writing, and the search for the audiovisuals comes after the script has been concluded. Park insists that he is, first and foremost, a storyteller, and that every element of his films must support the story in the best way. In that fashion, the script of the film, which is based on the homonymous manga, focuses on Dae-su, a businessman who is arrested for drunkenness, missing his daughter's fourth birthday. That same night, and for no apparent reason, he is abducted and forced to live in the same room for 15 years. When he is unexpectedly released, he is set on exacting revenge, although the sole evidence in his possession is the fact that he must accomplish this revenge in five days. A girl he meets at a sushi restaurant, where she works as a chef, decides to help him, once more with no apparent reason.

This combination is elaborately portrayed by two succeeding sequences – the one that Dae-su spends trapped in a room, and the moment of his escape. The first one has distinct, art-house aesthetics, as the pace is quite slow and the whole sequence takes place inside four walls, almost without any action, with Park focusing on showing the consequences the imprisonment causes to Dae-su. On the contrary, the scene where he escapes, despite its technical perfection, definitely moves towards the mainstream, as it looks like an action scene out of a Hollywood film, particularly due to the fact that a single man wins against tens of opponents. The abrupt cut at the end of the scene also moves toward this direction. The cult element is also evident in the film, in a number of scenes. The one where Dae-su is devouring a live octopus (which is an actual scene, not computer generated), the whole concept of Mr. Han, and both of the aforementioned sequences combine exploitation elements, in distinctly cult fashion.

Although “Oldboy” has revenge as its central theme, Park directs a movie with the actual goal of presenting another dimension, one that leads to repentance. The humiliation and ensuing catharsis are the primary concepts, and revenge, which creates chain reactions of growing hatred, is solely an element of the set, with the focus being on vengeance not as an act, but the reasons that lead to it and its consequences. The aspect regarding the consequences is the most obvious. Dae-su ends up utterly destroyed on all levels, because he wanted to exact revenge from the man who imprisoned him, with the fact that he was tricked into having sex with his daughter being likely the worst. This element brings the film closer to an ancient Greek tragedy, through a distinctly Oedipal concept. The case of Lee Woo-jin, on the other hand, shows the futility of revenge as an action for a man that could do so much with what he had, but instead decided to devote all of his powers to exacting revenge from a man who was, nonetheless, already destroyed.

“Oldboy” includes a number of truly shocking scenes and concepts. From the abduction of Dae-su, to his imprisonment for 15 years, to the actual reason behind it, and everything between, are rather shocking. The scene of him eating the octopus, the various bloody fights, the sex scene with his daughter, and the entirety of the ending sequence, definitely provide a shock element, which the spectator does not easily overcome. However, Park managed to inject his distinct, dark, and ironic sense of humor, in this otherwise onerous setting. During the corridor scene, when Dae-su asks the thugs for their blood type before he hands them a member of their team he had previously hurt. The whole concept of the character, with Dae-su acting like a caricature throughout the majority of the film. His interactions with his kidnapper, in a sequence mocking everything presented on screen concerning this kind of relationship. This very dark sense of irony finds its apogee in the very end, with Dae-su asking the hypnotist to make him forget that Mido is actually his daughter, in order to return to a relationship he knows is incestuous.

Park demanded a lot from his protagonist, including actually eating live octopus, but Choi Min-sik definitely rose to the challenge, sublimely portraying a truly difficult character. His ability to be equally convincing as he portrays a number of statuses and behaviors found its apogee in “Oldboy”. In that fashion, he starts as a drunken loser, to a man frustrated and perplexed by his fate, to a non-stop vigilante, to a lover, and to a man beaten and shattered by the disclosure of his actual relationship with his daughter. Furthermore, Choi manages to retain a caricature style throughout all these transformations, which perfectly suits the combination of shock and extreme humor Park wanted. Yoo Ji-Tae as Lee Woo-jin is also great as the impersonation of evil, a man so driven to destroy Dae-su that he cares about nothing else. Probably his greatest moment is during the ending sequence, when his true intentions and reasons are revealed, as he appears as a man so sad but so pathetic at the same time. Kim Byung-ok provides a cult element in the film as Mr. Han, while Oh Dal-su as the kidnapper manages to provide, once more, a comical aspect, even in this setting.

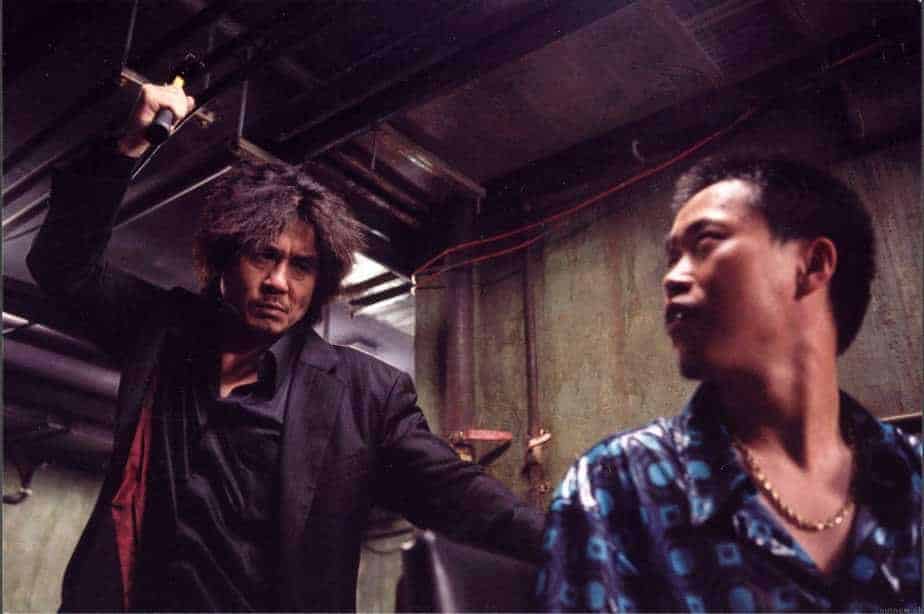

In one of the most elaborate action scenes ever to appear in cinema, Oh Dae-su confronts a number of armed henchmen set to prevent him from escaping, having a hammer as his sole weapon. The scene begins with Park's absurd sense of humor, since Dae-su asks the thugs for their blood type before he hands them a member of their team he had previously hurt. He then proceeds to attack them. The scene could be characterized as a bit hyperbolic, since in the end, he manages to win against so many enemies, but this act is not presented in a superhero fashion. Dae-su gets hurt quite a bit, he falls over a bunch of times, he is stabbed in the back with a knife that stays in for the rest of the fight, and he uses every dirty trick in the book to win, including playing dead. The final frame of the scene is also great with Dae-su smiling, despite the fact that a new bunch of enemies emerge from the elevator.

The scene was executed to perfection, but it took 17 takes over three days to achieve the result Park wanted, and is actually one continuous take. There was no editing whatsoever, except for the knife in Dae-su's back that was computer generated. As the scene progresses sideways with the camera following, the geometry of it is astonishing and quite reminiscent of old school beat-em-up games, like “Final Fight” and “Double Dragon”, with a sense that is heightened by the fact that the protagonist fights alone against scores of enemies. Park, however, has stated that the effect was unintentional.

Chung Chung-hoon's cinematography does wonders in the presentation of the complexity of the story and the intense aesthetics Park wanted to give the movie. Apart from the corridor scene, Chung uses bright colors, intentional grain, and color saturations, in an effort to match the extreme nature of the story without physically exhausting the audience. Park Chan-wook is one of the most prominent filmmakers in the industry in his use of the handheld camera, as he uses it to give his films a slightly shaky effect. This trait is also present in “Oldboy”. However, the movement and the angles he uses are very subtle, and the presence of the particular medium does not become so obvious, as it was in “The Blair Witch Project”, for example. Furthermore, the handheld camera gives a more direct view of the scene to the audience, actually making them think that they are a part of the movie. This trait is most eloquently presented in the final sequence, when Dae-su learns the truth and is actually filmed with a handheld camera as he crawls and begs.

The same trait applies to Kim Sang-beom's editing. Apart from the aforementioned scene, his editing is wonderfully portrayed in a scene at the beginning of the film, when Dae-su wakes up inside a briefcase on a rooftop, and meets a man with a puppy, who is about to commit suicide. Despite his intentions, Dae-su saves him and then tells him his story. The man seems to empathize, and after Dae-su has finished, he tries to tell his story, but Dae-su leaves him standing. The next cut shows Dae-su on the street and the man crashing from the rooftop onto a car.

Even if the exhausting analysis of the film has deemed somewhat preterit, “Oldboy” remains a landmark for Korean cinema and a true masterpiece