Kiyoshi Kurosawa is one of the key figures of the Japanese new auteurs' wave that emerged around the 1990s. Among many names that found their success at the festival circuit, V-Cinema market or in the less official ways of distributions, Kurosawa was immediately heralded as one of the pioneers of J-horror, with titles such as “Cure” (1997) and “Pulse” (2001) granting him a cult reception across the globe. No matter what genre, dysfunction or timeframe he picks up, there is a consequence in Kurosawa's body of work – a thrill that comes with a render of the environment, one that struggles with uncertainty and fear, and one that captivates the viewer's attention throughout the ambiguity of expressions. It's always a treat to watch a master resorting to his old tricks and leitmotivs, twisting his go-to formula to his needs, re-imagining one's language for the present needs.

This time around, Kurosawa leans towards the image of the past as his “Wife of a Spy” reflects on the experience of the Second World War, set in Japanese harbour city, Kobe, in 1940. As much as his period drama thriller grasps the political turmoil and genre-driven protagonist-antagonist clash, there's also a space for depicting women's agency in the patriarchal world, with a captivating performance delivered by Yu Aoi, the wife. Kurosawa prepared the script with his former student, Ryusuke Hamaguchi, and Tadashi Nohara (co-writer of Hamaguchi's “Happy Hour”). The result is surprisingly refreshing. In a seemingly old-fashioned, antique genre, they managed to imbue a much-needed resource, giving the whole a unique ambience of uncanny. Not to mention that Kurosawa's take on Japan's sins during the war abounds in a fresh perspective, on that should prevail among the audiences even now.

I met with Kurosawa-san on ZOOM during the recent edition of HKIFF. We discussed the idea behind depicting past over future this time, preparing the historical landscape for “Wife of a Spy”, why Yu Aoi is simply perfect, or the unusual vibe that 8K technology provided for the film. Since the movie revolves around the perception of the medium, we also tackle Kurosawa's approach towards the philosophy of cinema and his understanding of what film used to be in the past.

Kiyoshi Kurosawa was awarded with Silver Lion at 77th Venice Film Festival and nominated for many awards for this year's Asian Film Awards. “Wife of a Spy” has just started its US distribution tour, thanks to Kino Lorber. The interview was conducted and translated from Japanese by Lukasz Mankowski on the occasion of the Hong Kong International Film Festival.

First of all, how have you been these days?

I've been doing fine. There's not a lot going on in the industry for me, so I'm taking each day slowly as it comes, trying to enjoy this state while I can.

I'm happy to hear that. Comparing to your previous films, “Wife of a Spy” is your first attempt to focus on the past, rather than the fear of the future. Why have you decided to look back?

Indeed, from all of the films I've done so far, none would revolve around the past. No matter what genre I want to pick up for my film, there are always constant values I'm strongly attached to. These revolve around my protagonists: their happiness or their freedom. I'm always trying my best to grasp these notions. If you focus on the present, freedom and happiness seem easy to comprehend as they exist in front of our eyes. If one keeps on pursuing things that will bring them neither of these, then the probability of becoming a criminal is quite high. In that case, one simply starts to gradually sink in a very frightful reality, with one's sense of values slowly blurring into a fuzzy mass. Ultimately, I often don't have the slightest clue about what makes my characters happy or what brings them the taste of freedom. That ambiguity perhaps defines the stories about present times.

I've been giving it a lot of thinking to reflect on these notions by adjusting the reality of my film to the image of the past. I decided to set the story in the 1940s, right in the middle of the war. If we take a look at the sense of happiness or freedom people used to have back then, we can tell that people were constantly under a lot of pressure. There was barely any margin for self-realization. Although I felt that the story set during the war might be too plain for a contemporary audience, I still concluded that I want to depict the image of those who pursued their freedom back then. I wanted to give it a try, just for this once, because I never realized I could be able to make such a project. It started from my desire, but the flow quickly changed until it became the film.

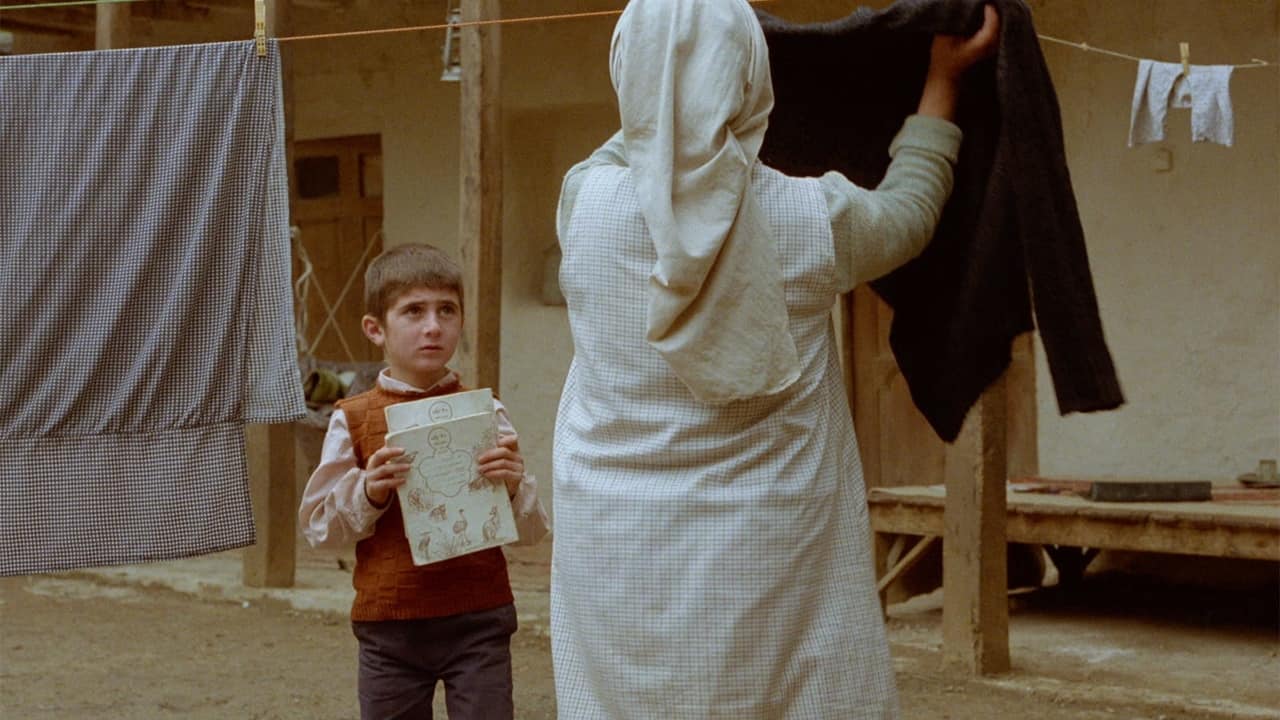

Photo: Kino Lorber

Since it's your first period drama, was there any particular challenges you had to face during the process?

For the precise reason that it's my first period drama film, some elements required a significant amount of preparation: translating the visual language, composing costumes, make-up or hairstyles. It was tough, but also fun. Of course, if you have enough money, you can do anything you want on your computer. The setting or the scenery of each scene can be designed. But that wasn't the case for us because our budget included none of these. To make the scenes look like they belong to the 1940s, we had to work around real locations. This approach has its troublesome limits, but we absolutely enjoyed this process.

The other thing I found particularly interesting, which on the other hand became quite a pain for the actors, were the dialogues. It might be difficult to grasp for those who don't understand Japanese, but the lines sound completely different from the language we use nowadays. We paid a lot of attention so that the language would also fit the reality of the 40s and 50s as much as possible. We tried to reconstruct the dialogues from the films of that period and the actors followed my guidelines so that their way of speaking would resemble the way people used to talk back in the day. And I guess that was the biggest challenge for them, although, for me, I can admit it was a real treat.

I was particularly captivated by the actors' ability to deliver linguistic nuances of the period. It made me think about the casting as well, especially about Yu Aoi. You have worked with her on previous occasions (“Journey to the Shore”, 2015), but what made you choose her this time?

Just like you said, it was mostly due to our previous collaboration when we worked together in 2014. She can act anyone she wants to so effortlessly. It's an ability that is absolutely difficult to achieve. If you look at other contemporary actors, you can see that not everybody is capable of that. Not only that, she can perform without any sense of hesitation. That made me think that it had to be her. It's not only that her skills are outstanding, but she also watched dozens of old Japanese films to prepare for the role. Actually, she has a refined taste in film, so that made her a perfect fit. There was no other choice, but Yu Aoi.

Photo: Kino Lorber

Here and in your previous films, you approach objects as living entities, almost like they have a soul of their own. In “Wife of a Spy” there's a lot of attention towards the film within the film aspect, but also towards the contrast of what's real and not. There's Sadao Yamanaka's “Priest of Darkness” (1936); Sadako appears in her husband's self-made film. It made me wonder about your approach towards the medium's power to question reality – do you perceive film closer to reality or fiction, imitation?

It's a very broad and difficult matter, but I would say it's closer to… reality. Or at least it's not artificial. Defining what's real is a hard thing to do, but the film itself is without a doubt a representation of reality. Like you rightly pointed out, the film revolves around the film's ability to work as a medium. There are scenes in which the ordinary room with white walls becomes a screening room. Once the projection starts, this is the moment when the film has its birth. That moment becomes important for the story, as it becomes its turning point. From that viewpoint, we can say it's a constructed narrative. But from a wider perspective, we are constantly surrounded by different sorts of screens: television, computers, mobile phones. There is always a projection of something around us. In a way, it defines our reality. In the past, when I was still a little boy, a projected image was something that possessed the qualities of the drama. As I gazed into the image, I started to realize it wasn't only a projection of reality that was in front of me, but a hidden world, full of meanings and signs; a world in which I could identify myself, one in which I could find the reflection of me. But above all, I felt there was something of me that I wasn't aware of. I could feel the flow of different codes and signals so I tried my best to embrace it and then absorb it. And I guess it was a similar case for many people in the 1940s. Back then, the film used to be a window for reality.

What became the reason for implementing “Priest of Darkness” into the narrative?

It is known that Sadao Yamanaka became the symbol of war sacrifice among the Japanese filmmakers from that time. “Wife of a Spy” is set in 1940, two years after the death of Yamanaka. At the beginning of the film, there's an atmosphere of sentiment revolving around the filmmaker's death. It's still there and protagonists are well aware of that fact. There were many things that Japan has lost during the war but among these that prevailed at that time was a sense of suppression. “Priest of Darkness” was a symbol of both the loss and what has remained. Yamanaka died at an early age, but not his films. The protagonists of “Wife of a Spy” watch Yamanaka's film at the local cinema. And since the film represents something unjust, I found that the characters will experience something profound. That's why I chose it.

Since we revolve around the topic of the image, it's worth mentioning that the film was recorded in 8K. But if you compare its smoothness with the graininess and texture of the silent films included in “Wife of a Spy”, the contrast is incredible.

That's true, it's a very film-ish thing. (laughs)

In a way, it also operates as a film about image. How did you work on establishing such an approach?

I'm surprised you've actually mentioned the aspect of the graininess of the film, as it's something very important for its visual side. Of course, my film is very film-ish and it revolves around a certain reception of the medium. That includes the desire to reflect on the texture of the image. But since we relied entirely on digital representation, it wasn't clear what approach I should follow. The image in 8K is the absolute of the digital technique. It's quite disturbing, to be frank. The textures are incredibly detailed and it has a very peculiar ambience so that it translates the vibe of each scene into something entirely different. Even if there's nothing in the frame, 8K technology makes you feel the presence of nothingness. I was surprised by it. The most typical example would be the tram scene from “Wife of a Spy”. Outside the window, there is pitch white. The image abounds in whiteness, nothing else. Since we couldn't rely on reconstructing the townscape of that time through CGI – an utter nightmare, if you ask me – I decided to leave it as a white blank image. This is the view of the outside world, and since it's achieved through a digital technique, all that one can see is the totality of white. It looks like there is no projection at all. But thanks to 8K, there is this different sense of air, a rare sense of ambience. Even though you know there's nothing there, for some reason it makes you think there is something; you simply start to look at something instead of nothing. 8K gives the image an uncanny texture of presence. That's the disturbing element of the art of 8K. For that reason, I do believe there is a lot of contrast in the aspect of graininess, but as for the 8K, this includes a very peculiar sense that it adds a mysterious depth to the image, this unique sense of presence. And it is precisely for that reason, that I decided to work with that technology in “Wife of a Spy”.

Photo: Kino Lorber

Don't you think that 8K makes the image simply too smooth and nice at times?

I agree. It becomes way too nice. But even still, there is no need to make it dirty. I think there is a keen 8K beauty that can be achieved only through 8K. The key is to match the aesthetics with the narrative, the quality of the image with what you want to convey. This is something we worked on with the art team. Another very demanding process. The whole thing with adjusting the visuals to our needs needed a lot of attention. We wanted the particular beauty of digital form, but one that would be justifiable for the setting of the story as we didn't rely on the film tape to match the times. And we were able to do so because we grasped the essence of fiction. It wasn't easy. The process of finding the right artistic expression was filled with little details. And since, eventually, we were able to bear with 8K, we managed to achieve something genuine.

And what about the script? You wrote it along with Ryusuke Hamaguchi and Tadashi Nohara. Were there any particular difficulties?

I think the two of them made a wonderful job with the script. 80% of the story is them. They had a chance to work together before on the occasion of Hamaguchi's “Happy Hour” (2015). That's a work full of wonders, although the film is very long. And that was something I was aware of, that the long formula works for them. I wanted to make a film that wouldn't exceed two hours, so from the start I was thinking about what can we do to compress the story. My part was doing exactly this; making sure that the story won't lose its impact, whilst becoming a bit more compact.

Some of the scenes reminded me of “Happy Hour”. Especially concerning Yusaku's lines and the way sometimes he delivers his dialogues toward the camera.

When we made this, I wasn't intentionally following up on this film (laughs), but since you've mentioned Yusaku's dialogues, I must say there are a lot of lines his character has. Even though we had to cut some of them, there are still so many left. It's a character full of words. Issey Takahashi [who played Yusaku] managed to do a wonderful job with this role, as he delivered all the lines beautifully without any trouble. We wondered what should we do to capture such a character, how we should approach the shooting. So I must admit that there was some anxiety regarding such long dialogues.

Many critics heralded the film as a very Hitchcockian. There is a lot of suspense that determines the flow of the narrative, a device that seems very important in your work in general. How did you work on scheming the unfolding of the suspense?

Before writing the script, Hamaguchi and Nohara delivered a prototype of the story. Even there, we decided that it needs to be a bit shorter. The story as a whole was based on suspense. This is when we realized that the scenery of the world amidst the war required a particular sort of one. There are plenty of suspenseful films from America or Europe that depicted the reality of war, but not so much in Japan. In a way, we knew that we're doing something that wasn't typical for Japanese films, but we looked for the good suspense from day one, not the cheap one. As for Hitchcock – I'm very fond of his work, but with this film, I wanted to avoid any connection with him. I tried not to imitate him to the extent I wished that nobody would compare me to Hitchcock at all. (laughs) I intended to make it as far from his style as possible, so when the comparison kicks in, I can only be fair with myself, that I didn't want to imitate him. But this is how things are. You can't do anything about it, that's the way the history of the film evolves. Hitchcock was the genius of suspense, so if somebody says my work is similar – well, I can do nothing except to accept these words.

In your early films, you depicted a certain fear connected with the uncertainty about the end of the millennium. I was wondering, what is that you're afraid of right now?

That's a very difficult matter. There are a lot of things that I'm now aware of that I'm scared of. I know that I wouldn't be able to reflect on them 10 or 20 years ago. Sure, the way people perceive things started to become more diverse. We're confronting the vastness of information that floats through our fingers. Our sense of values is constantly questioned and there is simply too much of everything. And apparently, we became so free and independent that we lost our attention towards what is near us. I have a feeling that despite living nearby someone, be that our family or neighbours, we can still be so much different from each other and have an utterly different sense of values. It became so easy to polarize with each other because we have been granted so much space and freedom. That is something that scares me a lot.

Photo: NHK/NEP

Do you consider “Wife of a Spy” a critique of Japan?

Critique is not that simple thing to achieve, but I consider it as a critical reception of Japan's attempts to constantly plunge forward at the time. There is a lot of negative thoughts on Japan's way of operating during the Second World War. That is for sure. Especially towards the military authorities. In that sense, I do criticise what they did and how they approached things.

I'm asking this because I noticed that in Taiji's room there is calligraphy of the pictograms in the background, 忠孝, that means ‘loyalty and filial piety'. Did you choose it on your own?

You've noticed a quite interesting thing. I'm impressed. This was proposed by the art director, and we even had some disputes regarding this, as I struggled with how I should decorate the room of Taiji, head of military police played by Masahiro Higashide. This is the place where he sits in many of the scenes, so I wanted the background to be meaningful.

In one way, we could easily grasp the essence of the place by simply putting the symbol of Hinomaru, the Japanese national flag. It's both very meaningful and realistic. It would make sense. However, if you decide to include the national flag in the scene, you start to wonder about its real meaning. And as expected, you start to ponder, is that what I wanted to convey? Will it become easy to understand? At some point, I started to oppose the idea of including Hiromaru.

Regarding what you've just said, there's a lot of Japanese people who tend to criticize Japan as a whole and that would also include the head of military police, Taiji, and his conduct. But with national symbols such as Hiromaru, it was used for numerous purposes and, depending on the period, its symbolical meaning also became different. To the extent that it became something more than it really was; it extended its original meaning, comprising a lot of misunderstanding. It simply started to mean something else. It became something else, not just a country's symbol or a flag.

That's why I wanted to use something that would be particularly appropriate for this moment of the war; a symbol that would reflect on what we were trying to grasp in our storytelling. And we started to think what would be the right choice. We didn't find it right away. Along with the art team, we decided to combine two Chinese signs, one referring to loyalty and fidelity, second to filial piety. In our mind, it did fit the idea of actuality, as these two words refer to a very important notion for Japanese people, this is to say, a notion of faithfulness that leads to a particular sense of values that for many defines the relationship between parents and their children. It's very representative, but also quite simple. Apologies for such long reasoning, but we immensely struggled with the right choice of what would fit Taiji's room.

Photo: Kino Lorber

I wanted to reflect on the past a little bit. Lots of the attention towards your work was achieved through film festivals. But in some way, much of your audience comes from illegal sources as well. How do you reflect on piracy from your current perspective?

To start with, this is a very complex thing with no easy answers. To be perfectly honest, once the work is done, it doesn't really matter how it is watched. I'm simply grateful to those who spend their time with my films. As for piracy and the violation of copyrights – watching films illegally on the internet is technically a crime. It's not allowed. That being said, I'm always happy when someone can watch my film. I really am. But, it's always good to pay for the artwork. It comes with the copyrights, but also with other aspects. As for Japan, we, filmmakers, are not those who own the copyrights. This is always a separate company. Technically speaking, we don't get the money that is paid for the artwork once it's up there, as it goes to the distributor company. I don't get a single penny at that stage.

With the rise of streaming platforms and online screenings, it became even more blurry. It's not about people not willing to pay to watch films, but rather about watching films in general. Sometimes there is no other way to watch something, outside of pirating it. It's committing a crime, but it's still someone doing me a favour because the film is watched nonetheless. I think the best system would be that people should pay for the films, even a little amount of money and some of it should be distributed to the filmmakers. It would be a good system, but difficult, if not impossible, to achieve. That's why people keep on pirating the films they want to see. Of course, I can't say more. Crime is a crime!

Since you've established yourself as an independent filmmaker, I was wondering what do you think about the current new generation of indie film directors? Can we even say there is something of a new generation in Japan?

I think there is. Back in the day when we started, we simply wanted to make films. We found it extremely interesting. It was fun. We took 8mm film and shot whatever we wanted. Such self-made art brought us a lot of joy. I guess it's a bit different now. These young, aspiring filmmakers don't only shoot films as a hobby. Aside from the digital form that became different, they make their films mostly for film festivals. They aim to be invited to the international scene. If we look at Japan in the last decade, we can notice the case of “One Cut of the Dead” (2017), an independent film, which unexpectedly became a huge hit on the domestic ground. It showed that an independent film can become commercially successful. It also gave some expectations, perhaps some hope as well, for the independent filmmakers that maybe in the future they will be able to earn some money for their work. And this is something that we cannot possibly compare with the past, even though we had high-quality independent films back then.

With that said, I think if you are doing things independently, just have as much fun as possible. Don't bother with festivals or if your title becomes a hit or not. It's not bad to be zealous about such goals, but at some point, you might as well be fed up with all the commercialism related to your work. The most beautiful thing about the independent film? It's not related to film festivals or box office – it's about freedom and being independent. Do what you want to do; do it, even though you can fail. If you fail, well, that's the experience. You can learn from it. There's meaning in it. I, myself, had a lot of privilege to work at a time when I could simply enjoy the process of filmmaking while being irresponsible. But there was fun in it. Right now, young filmmakers make wonderful films. There are lots of interesting titles released in Japan every year, both commercially successful or independent. But, for those who make the latter ones and who strive to be tied to the commercial world – it's not easy to find one's way into it. It's not like young indie filmmakers can't taste different reality, but it seems there are not many ways to get in and it requires lots of determination. And if they do, eventually, their desire to make commercial films is simply weaker than they initially thought. At some point, all their zeal vanishes and they realize the independent films they've made before are more than enough and the privilege of independence is what really starts to matter. The experience of international film festivals stays with them, but they are also able to appreciate single screenings on the local scene at small venues. I consider it as such a waste, that independent filmmaking and commercial filmmaking are two separate worlds that seem to be so detached from each other.