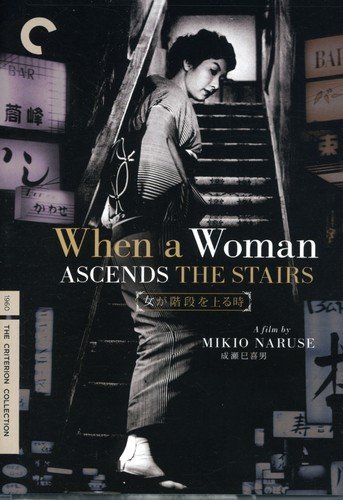

Considered one of the best Japanese movies of the 60s (and all time) Mikio Naruse's masterpiece is an ode to realism and minimalism, as well as a rather thorough study of the role of women in the Japanese society of the 60s, stripped from any kind of disillusions.

Every afternoon, young widow Keiko leaves her small apartment to attend a bar in Ginza, where she entertains entrepreneurs after they finish work. Due to her kind nature, the younger girls at the bar call her “mama”, acknowledging her finesse and beauty as the apogee of their profession. Kenichi, the man in charge of the bar, has feelings for her, but he keeps them hidden, while retaining a respectful distance from her, as much as a meaningless relationship with a young and ambitious barwoman, Junko.

As time changes, girls from the other bars in the area resort in unethical tactics to draw in clients, mostly revolving around sex, as the competitions for the patrons intensifies. Keiko, however, refuses to change, continuing to dress in traditional attire and turning out the sexual advances of her clients, in a behavior, though, that states that she has outgrew her profession, even more since, at her 30, she was considered an older woman, even outside the particular line of work. Furthermore, and considering the aforementioned and the fact that she still has to provide for her elderly mother and unlucky brother, she finds herself at a crossroads: either to open her own bar and be financially independent, or get married and lean financially on her husband. The first choice will definitely involve granting the aforementioned sexual favors, while the second, dishonoring her late husband to whose memory she is still devoted.

Naruse creates a disillusioned, melancholic, and deeply tender portrait of dignity and patience. Using the repeated sequence of Keiko ascending the stairs to the bar, he depicts the transition from her real life to the professional one, which demands a radical transformation. The strength she needs to exercise a profession she both loves and despises is mirrored in her narration in the beginning of the movie: “Night fell. I hated climbing those stairs more than anything. But once I was up, I would take each day as it came”

Naruse's trademark pessimism is not missing; Keiko seems to find obstacles any time she tries to achieve freedom. She goes back for a bit, but eventually, every time, she ends up ascending the stairs. At the same time, and as per her aforementioned words, the stairs provide a sense of relief from her rather hard daily life, while highlighting her strength and courage. Furthermore, Naruse uses the concept to mock the dogma of “climbing to the top”, which is the one always dominating the world of entrepreneurs, whose members also provide the main clientele of the Ginza bars.

At the same time, he makes a comment on the struggles women faced in a male dominated society, while highlighting their only weapons: cunningness, sensuality, and charm. Lastly, he also comments on family ties, which in this case, are showcases as so strong, that no one can break them.

Hideko Takamine is magnificent as Keiko, elaborately depicting a complex character who actually lives two radically different lives. Her performance is in perfect resonance with Naruse's cinematic approach, as she is utterly measured and composed throughout the movie, also in the way society demanded from women to act at the time. Tetsuya Nakadai is also quite good, even if in a much smaller role, with the scene of his confession being his most impressive moment in the movie.

The minimalist mentioned in the prologue finds its apogee here, as the outside shots are essentially non-existent, the production design as simple as possible, and the black and white cinematography of Masao Tamai, strict and economical. Eiji Ooi's editing results in a relatively slow pace, which, in the way Naruse placed one shot over the other, result in an impressive flow, where the cuts are barely visible. Lastly, Mayuzumi Toshiro light jazz fits the general aesthetics to perfection, again without exaltation.

The sincerity with which Naruse deals with his subject, the way he has shot, and his dedication to realism deem “When a Woman Ascends the Stairs” a true masterpiece.