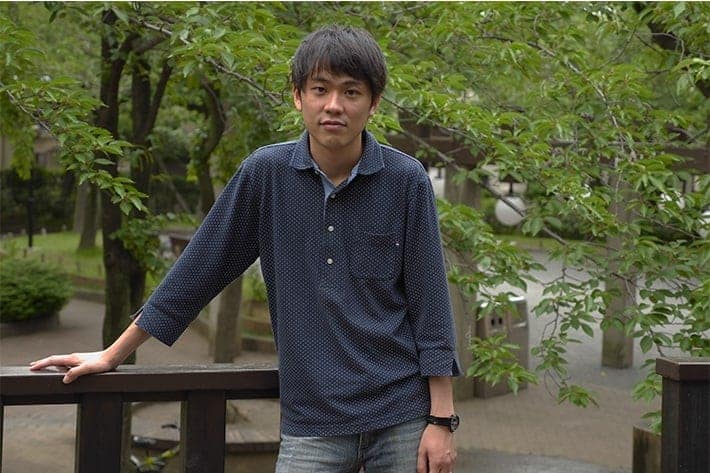

Director for Mainichi Broadcasting System, born in 1965. After graduating from Waseda University, she joined Mainichi Broadcasting System in 1987. After working in the Secretary Department for the President, she became a news reporter in 1989, covering education on-location while being part of the press club for the police and administration of justice. In 1995, when her home was hit by the Great Hanshin Earthquake, she lost all of her essential utilities, and yet she continued reporting for the Kobe bureau office. Since 2015, she has been working solely as a documentary director and

released three documentaries a year for a total of 18 works. (Her Eizou series is a local documentary program started in 1980 that broadcasts late at night once a month. The program captures various social problems on camera and has broadcast over 500 works that reflect the times. Saika has individually won the Broadcast Woman Award in 2018. She also wrote Education and Nationalism: Who Suffocates the Classroom? (Iwanami Shoten) and What Kills Reporters: From the Filming Site of the Documentary in Osaka (Shueisha Shinsho).

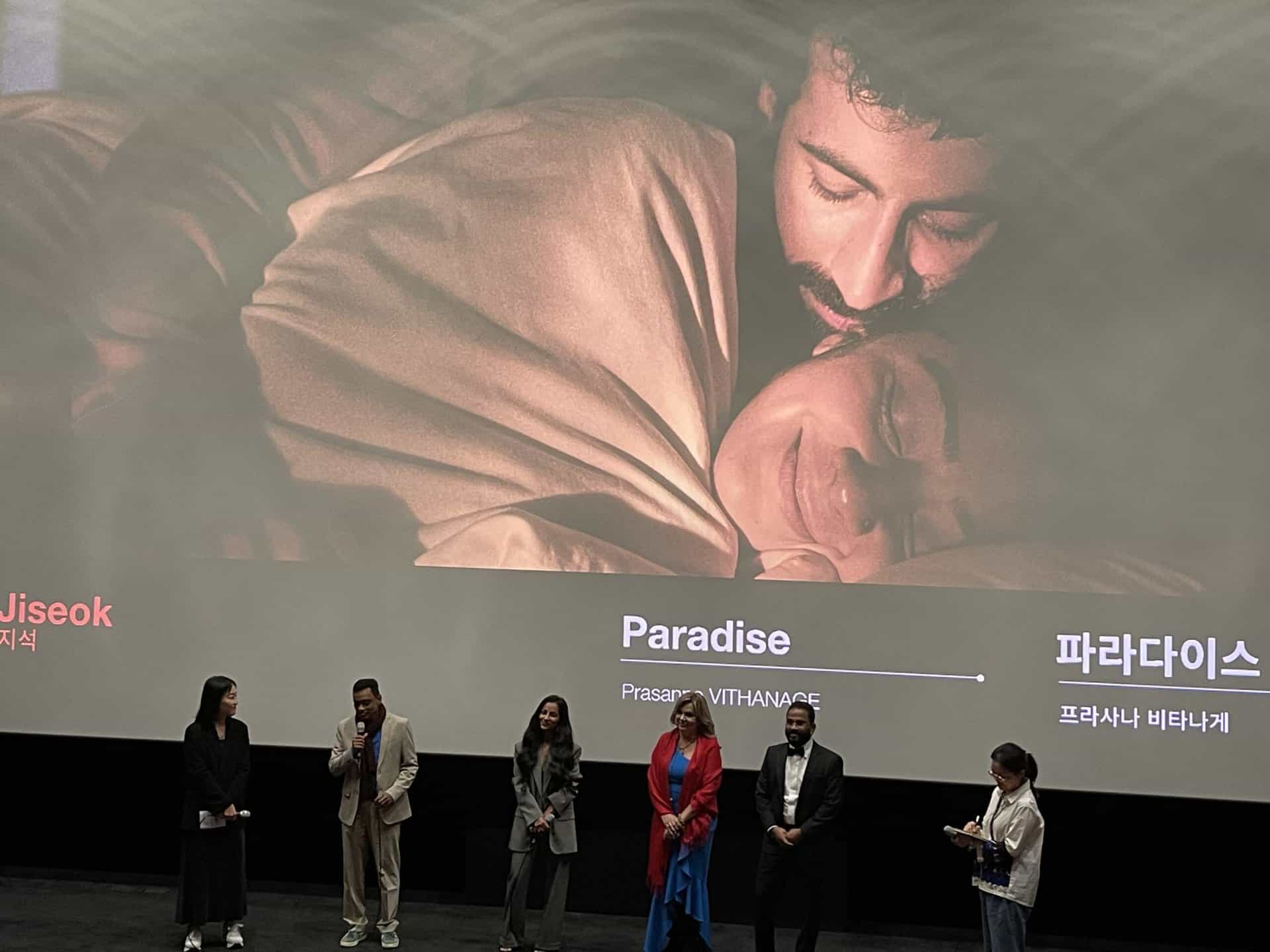

On the occasion of her documentary Education and Nationalism screening at Busan International Film Festival, we speak with her about Japanese Education, Takashi Ito, Abe's policies, revisionism, and many other topics

Education and Nationalism screened at Busan International Film Festival

Why did you decide to focus on the issue of education in Japan? In general, how would you describe Japanese education at the moment?

I've been covering the education industry on-site for many years, and if I had to put it simply, it's because of a sense of impending crisis. Before 1945, Japan's education system centered around the idea of “swearing loyalty to the emperor and loving one's nation.” Once Japan lost the war, the Basic Act on Education drew a line between the government and public education, which maintained its independence. However, there was an amendment in 2006 in which a nationalist clause was added: “fostering the value of respect for tradition and culture and love of the country and regions that have nurtured us.” After this, the wall between education and government crumbled under the Shinzo Abe administration over many years. We're now witnessing an abnormal state in which historic terms are being rewritten in textbooks.

If I understood correctly, each prefecture can choose their own textbooks for the schools in their area. Is that the actual case? Are students in different regions being taught through different textbooks?

The educational committee in each city, town, or village of each prefecture has meetings to compare which textbooks should be used in public elementary and middle schools. When these have been selected, teachers on-site are provided documents and such in order to study and evaluate every textbook for each subject. The textbooks used can vary based on the region, but it worries me that subjects like social studies tend to mainly use texts from major publishers. In contrast, high school textbooks are decided by each school, so those have fewer chances for government intervention.

Why is the issue with Military Comfort Women such a significant one for Japanese governments? Why not just apologize? Are they only afraid of the reparations the victims might demand?

In the Kono Statement, the Japanese government expressed “apologies and remorse” in regard to the comfort women issue. However, it was later rebutted by conservative politicians and critics who say it “goes against the truth,” calling it a “masochistic view of history” that looks down on Japanese people. There have been many who have called for comfort women content to be removed from middle school history textbooks, thus making it into a political problem. People who want to trivialize the history of Japanese soldiers causing pain, in addition to the disgraceful behaviors of such soldiers violating women, are rejecting historical facts and bringing narrow-minded arguments in which they question whether women were in fact forcibly recruited. The Japanese side is claiming that despite having apologized and paid reparations, the Korean side is still repeatedly bringing up the issue. Now, the Kono Statement has been singled out, and political influences are pushing for a revision or total retraction. The Ministry of Foreign Affairs has also become more insular, which has an impact as well.

In general, why do you think Abe's government pushed these revisions so intently? Do you think that he was trying to change the constitution for Japan to go to war again? Do you think that after his death, his plans will stop?

It is a fact that those who want to “revise” the Japanese constitution are passionate about rewriting history textbooks and accuse existing textbooks of being written from a left-wing perspective of history. Behind their exterior motives, they have the desire to return the Self-Defense Forces into a formal army and once more become that strong army that defeated China and Russia. Constitutional reform is part of the Liberal Democratic Party's platform, and with fewer pacifists in the party now, I believe that plans of government intervention in education will be difficult to stop.

You have managed to gain access to many people who are responsible for the revisionist tactics presented in the film. How difficult was that and how did you manage?

It might be that the title “Education and Nationalism” bore fruit. The title was translated into English as “Nationalism,” but the Japanese word also has the meaning of “patriotism.” When I asked for people to participate, I would thoroughly explain my objective and repeatedly contact them through letters, emails, and phone calls. I would simply be sincere and request an interview, saying “I'd like to hear your thoughts.” It was not difficult.

What is your opinion of Takashi Ito?

If you are an academic studying modern history, Mr. Ito is an authority figure whose research papers you cannot avoid. Currently, many academics that study history and government are pupils of his, and believe the reason he did two interviews with me so confidently was because of his pride as an academic.However, it is said that in 1970, his own claims in his history studies were slandered unfairly by left-wing academics, who were the main faction at the time. I believe that perhaps his ideas regarding what he considers shallow left-wing academics, and the left-wing itself, have solidified. Perhaps he is a successor to Tokyo University history academics, which is said to be emperor-centric historiography from before the war.

Are you afraid that the accusations towards Abe will bring you trouble, even more so considering that he is now dead?

Since those online have decided that criticizing Mr. Abe is “anti-Japanese,” I was worried about online backlash at first. However, after the film was released, I realized my fears were unfounded. I expected the right-wing activists to harass me, but that actually didn't happen at all. I saw no change after Mr. Abe's death. While I am a bit careful, I do not feel any danger towards myself.

The documentary screened in Japan and thousands of people have watched it. What kind of reactions did they have?

“It's a political horror that sent chills down my spine.” “You did a great job making this.” “Japan's in danger.” “I couldn't stop crying.” There were all kinds of reactions from viewers. Some have also blamed me for being biased. However, I think they could also feel my desire to use this film as a springboard, to begin discussions about textbooks and education. This film was made public on May 13, 2022. And as of now, October 21, it has moved 40,013 people. I hear that is an impressive feat for a documentary film.

What is your opinion of the Japanese documentary industry nowadays? Do people attend cinemas to watch documentaries?

I think there are many viewers who try to learn about society and the world through documentaries. It seems that people are seeing the reviews and articles and coming to the theater, not only fans of documentary films, but people who feel there is something off in current society.

Are you working on any new projects at the moment?

The program Bashing: Behind the Source, which you could call the TV version of Education and Nationalism, would depict members of the Diet who would interweave truth and lies and spread them online, slandering academics as “anti-Japanese.” There are also administrators of hate blogs that incite discrimination toward Zainichi Koreans. As society overall shifts more toward the right, I fear that a dangerous government structure is forming, in which they spread rumors and fake news to the public and push them toward populism, find pleasure in discrimination, and try to trick people who are not in their favor. Severe conflict and division are making an appearance as a global trend, and Japanese society is growing unstable. I would like to dive further into covering why this is the case and how this situation will develop.