10. Arc (Kei Ishikawa)

A surprising aspect of “Arc”, which turns out to be one of the most enjoyable, is that rather than delve into a sprawling sci-fi saga about the worldwide effects of immortality, we're instead presented with a far more personal story. Sure, we occasionally cut to a chaotic Eternity press conference or see a news update in the background, but, for the most part, the film is focused on Rina and her personal journey in this new world. However, this is not to say that Ishikawa doesn't touch on the broader social questions concerning eternal life being for sale, notably the early exclusion of poorer folk from the revolutionary treatment. (Tom Wilmot)

9. But It Did Happen (Yuichi Suita)

Yuichi Suita's direction is utterly meticulous, with each of the frames being perfectly constructed, lighted, colored (mostly in pastel colors), acted and shot, in a way that shows his intense attention to detail. The result is exquisite, both in terms of visuals, but also in terms of context, with the way he has chose to make his comments being ingenious, in a style that is equally laconic, measured and eloquent. Furthermore, the editing gives an excellent rhythm to the movie, as dictated by the few movements we witness, exclusively deriving from the simultaneous motions of the two girl students. (Panos Kotzathanasis)

8. Education and Nationalism (Hisayo Saika)

The presentation of the whole concept is as realistic as it is shocking, with Saika having done a rather thorough investigation, while managing to include interviews with members of both sides. At the same time, she pulls no punches in her comments, openly talking about political pressure, direct government involvement, and revisionary tactics that derive from the members of the “Abe group” who seem to have taken key positions in all hierarchies of the Japanese system. At the same time, and although not clearly answered, the question for the reasons for all these actions, which essentially aim at people forgetting the blights of war, also gets a reply here: The current government wants Japan to be able to go to war once more. (Panos Kotzathanasis)

7. Plan 75 (Chie Hayakawa)

In this finely plotted story, strands occasionally overlap, as we follow the situations the five characters are facing. A young immigrant nurse Maria (Stefanie Arianne) is trying to come to terms with her new job which very much differs from what she was trained to do. Instead of helping the elderly to live, she is now helping them to die, and although this business pays much better, it is by no means easier to cope with. Plan 75 call center agents Yoko (Yuumi Kawai) and Hiromu are starting to examine their involvement with the project the moment they establish a connection with their customers, in Yoko's case with a woman she slowly gets to meet better, and in Hiromu's by developing strong emotions to his estranged uncle. Unfortunately, their characters are slightly underdeveloped, but nevertheless important to introduce a different perspective coming from young people. (Marina Richter)

6. Shin Ultraman (Shinji Higuchi)

Again as in “Shin Godzilla”, the most obvious traits of the movie are two: The first one is the frantic, sttripped from any kind of nonsense editing by Youhei Kurihara and Hideaki Anno, which results in a truly thundering pace that actually allows for the plethora of episodes that take place in the 112 minutes of the movie to unfold in their full glory. Furthermore, the news piece approach in the unfolding of the events works quite well here, ideally progressing the story, with Keizo Suzuki's cinematography capturing the different settings the humans inhabit, with an unexpected but also rather pleasant realism. The second is the rather big budget that has allowed for all the gigantic creatures to appear quite impressive, either on the Earth or eventually into space. Their movement, the disaster that accompanies their every appearance, and even more outstandingly, their fights, are a true wonder to look at, in an SFX style that also shows how the whole tokusatsu/kaiju category has evolved during the last years, with the winks at the “Attack on Titan” being quite obvious occasionally. At the same time, “Shin Ultraman” stays true to the original franchise, with the main character's signature movements being the same, as much as his overall appearance, in an element that also induces the title with a very pleasant retro element. (Panos Kotzathanasis)

5. All Summer Long (Yuki Horiuchi)

Spanning the course of just one night, these events run in tandem with one another, overlapping each other freer than the characters whose lives become intertwined by fate's grand designs. Horiuchi's characters are splendidly aloof, their situations as deadpan as the expressions on their faces, unravelling their intricacies one awkward laugh at a time. Stemming from the wild incompatibility between the free-spirited and the reserved, the meek and the bold, “All Summer Long” playfully teases how such a word is void of any substance, prodding and poking how hilarious dissimilarities are what make life just a little more interesting. And yet, for all its whimsy, for all its awkward pauses, the film teeters above a sinister realm, as if one misplaced step forward would draw out something ugly and repulsive; this is something the movie acknowledges, offering glimpses behind its sweet facade with no more than brief nods, but the brevity does nothing to soften the impact these nods leave. (James Cansdale)

4. Small, Slow but Steady (Sho Miyake)

The bond between the aspiring boxer and her trainer is given in warm, accessible tone, and this is something Keiko Ogasawara was very particular about in her book. As we watch his health deteriorating, we can understand what this unexpected situation means for Keiko whose life is build up on the notion of trust to very few people in her surrounding. Not only the book, but the film as well gives an insight into the close-knitted boxing community not used to having a woman being taken seriously, and even less, someone with a disability. (Marina Richter)

3. New Religion (Keishi Kondo)

Channeling the dreaminess of Stanley Kubrick's “Eyes Wide Shut” and Kiyoshi Kurosawa's “slow terror” style, Keishi Kondo creates a world where everything seems to be a symbol, and reality, dream, nightmare, past and future co-exist. The result, although intensely complicated, is excellent, with Kondo creating an atmosphere of disorientation, horror, and implied/lurking violence that carries the movie for the majority of its duration, implementing all of its cinematic elements. (Panos Kotzathanasis)

2. Sanka: Nomads of the Mountain (Ryohei Sasatani)

Ryohei Sasatani directs a very sensitive and delicate film that unfolds in two axes: the coming-of-age one and the one revolving around the Sanka and the reasons that led to their demise. The first aspect revolves around Norio, who is portrayed as a teenager completely lost, living a life he does not want to, under the pressure of his father. His discomfort is evident in every move and word, while the fact that he is bullied at school and seems to have no friends, also add to his issues. As time passes, it becomes evident that the gap his mother left is too big, with the boy feeling the lack of family intensely, particularly since his father is mostly absent, and even when he is present, the only thing he does is pressuring him. This pressure also derives from the fact that the people in the village consider him a hero, and in essence, expect Norio to show the same level of excellence. His grandmother does his best to soothe him, but it is evident she cannot succeed. (Panos Kotzathanasis)

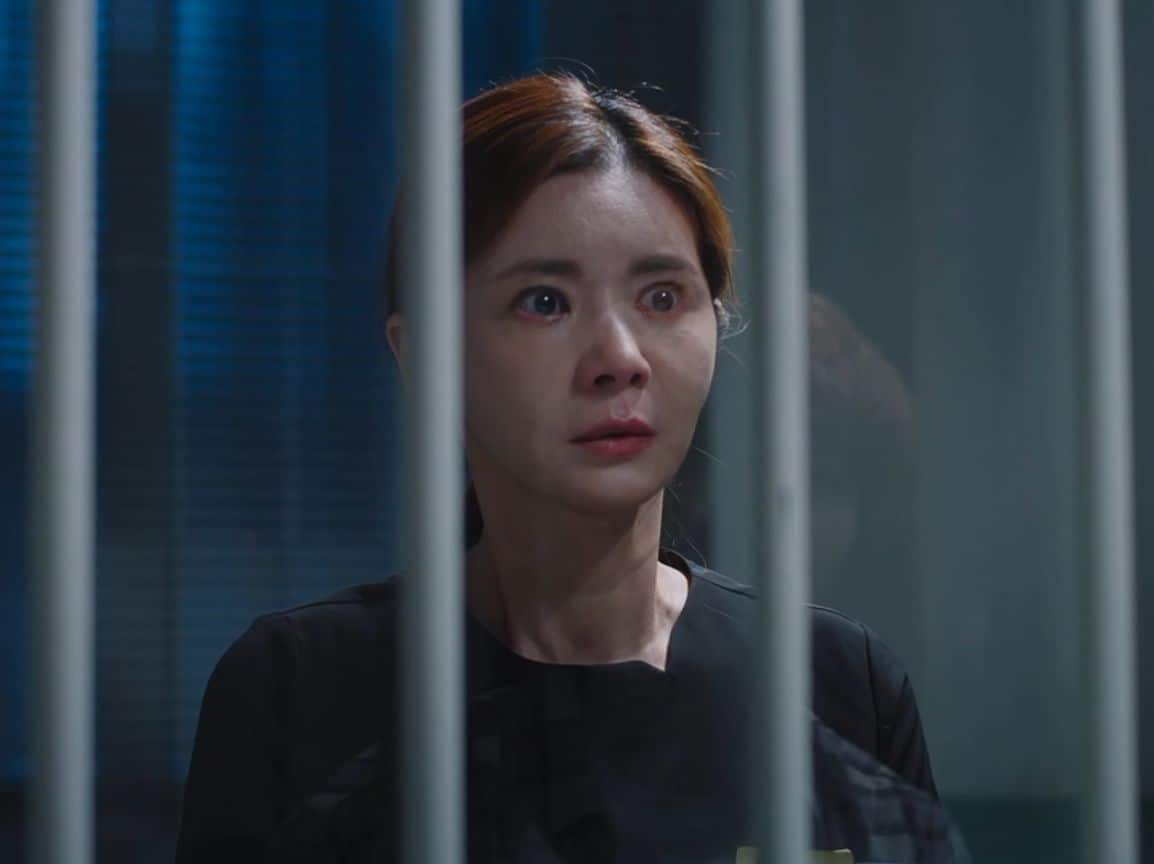

1. December (Anshul Chauhan)

Anshul Chauhan directs a film, based on a Rand Colter and Mina Moteki's script, that is a courtroom drama at its core, but also manages to move in a number of different, quite interesting directions. In that fashion, probably the most appealing aspect of the movie is its characters and their interactions. Katsu's inability to move on, and his downward spiral after his daughter's death is one of the most impactful elements here, as much as the fact that his only raison d'etre is making sure that Kana is never free. Sumiko, in contrast to her ex-husband, has managed to move forward and start her life again, but finds herself drawn into what happened seven years ago through Katsu, a decision that has many consequences in her life. The way the time they spend together changes the two of them, in almost complete antithesis, is another great trait of the movie, with the sum of all the above owing much to the great performances by Shogen and MEGUMI respectively, and their great chemistry throughout the movie. (Panos Kotzathanasis)