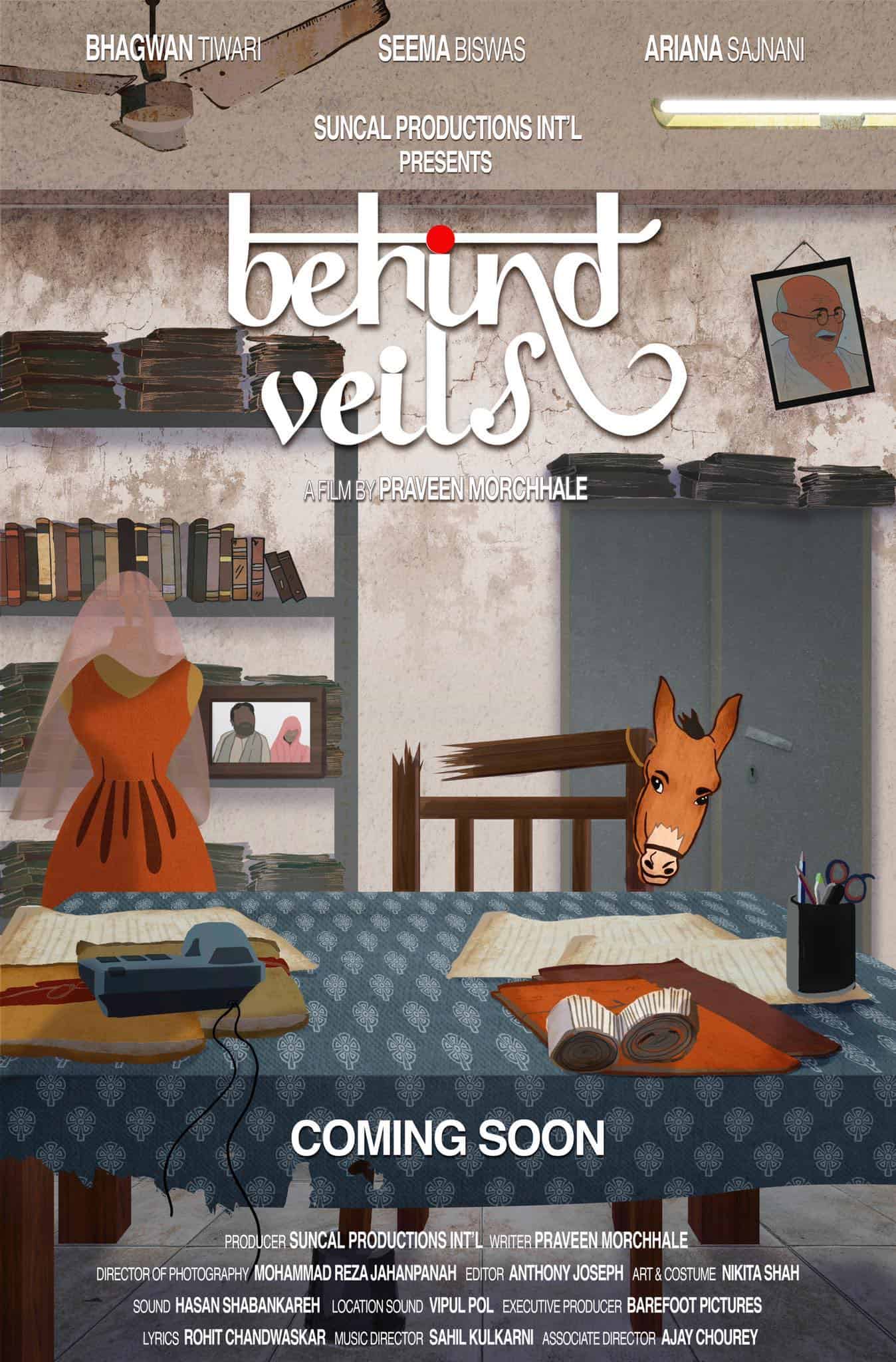

As he proved with the excellent, multi-awarded “Widow Of Silence”, Praveen Morchhale has a truly astonishing way of finding humor in the most extreme circumstances, eloquently commenting on situations and discrepancies of the system that can only be described as dramatic, in a fashion, though, that does not become melodramatic, or even worse, poverty porn. This cinematic approach finds its apogee in his latest work, “Behind Veils” a satire that seems to touch every aspect of the current system in India.

“Behind Veils” is screening at Vesoul International Film Festival of Asian Cinema

Ana, he US-educated, New Delhi-resident daughter of the recently deceased Sumanghal Sharma returns to the village he grew up in, in order to meet his family for the first time, as her grandmother ostracized him from their house years ago. At the same time, she wants to fulfill his last wish of building a library in the village, and for that purpose, she carries a mass of books with her. In the village, she meets her grandmother, who is now obsessed with social media and particularly Facebook, the local barber who doubles as a masseur, and the local political leader, Bhaiyyaji. The latter, however, is not exactly a virtuous leader as she soon finds out, since he has taken ahold of her father's property and refuses to give it back, a tendency he seems to have repeated a number of times. Furthermore, her request to build a library is met with much resistance from his side, since he thinks that if people get educated they will kick him out. Instead he throws her to the clutches of bureaucracy, asking her to bring a NOC, a no objection certificate from every one of the town's authorities, all of which are in his payroll, one way or another. Thus begins a kafkaesque mission that brings her against all aspects of the Indian system, with tragicomical consequences, not to mention an election.

Morchhale adopts a satirical approach from the beginning in order to present the dramatic events that take place in the story, which does not actually cease until the ending of the movie. Starting with the internet-obsessed grandmother, whose questions and overall attitude provides laughs throughout the movie, and continuing with the differences between the villagers and the city-woman, which actually include language issues, and the reason her father was ostracized for marrying outside their religion, the narrative here shows its face quite eloquently from the get go. The turning point, however, begins with the appearance of Bhaiyyaji, an uneducated, corrupt, greedy, racist man who seems to embody all the issues of the political system in India, including the way he actually plays it in his hands.

Through her effort to follow the legal way in order to get permission to essentially donate a library to a village that really needs it, and the whole absurdness of the NOC, Morchhale manages to comment on an even further number of institutions and professionals, including the police, the judicial, social workers, educational workers, contractors, and the way all of them are connected through the concept that seems to be the king in the country: bribery (or money if you prefer).

As the story moves forward, a number of additional episodes bring even more critique, with hospitals, religion, customs and the place of women in Indian society getting their share. Morcchale, however, keeps the best for last, with the elections and the way they are conducted in India (including donkeys, women who look like bollywood actresses, and again bribes) offering as much laughter as they offer food for thought.

The whole path the protagonist follows, and essentially the whole narrative, reminds intently of Zhang Yimou's “The Story of Qiu Ju” but Morchhale's approach is much more comical and even happy-go-lucky for the most part, a tactic that is cemented in the almost Shakespearean ending. The ending comment is also interesting in its pragmatism, with the director seeming to state that one can only fight the system by being even unreasonably persistent, while also “winking” at the power of women, who might as well be the most appropriate in this case, to bring change.

The intent colors of the cinematography fit the overall aesthetics of the movie, while a number of frames, such as the one where the family is eating inside the house all together or the one where the “bad guys” are sitting beneath a tree, are truly memorable. The same prowess applies to the editing which moves in the same, comical/deadpan direction, particularly with the way the scenes follow one another.

The only issues with the movie are the number of episodes, which one could say go a bit too far in their abundance, and extend the duration a bit more than needed. Also, some moments of music here and there would definitely benefit the entertainment offered, although the ending compensates in that regard.

The acting is in perfect resonance with the overall aesthetics, with Ariana Sajnani as Ana providing the anchor where every other performance interacts with, in a measured fashion that works quite well here. The ones who steal the show however are Seema Biswas as the grandmother, Bhagwan Tiwari as Bhaiyyaji, and Ajay Chourey as the Barber, with their whole demeanor being hilarious on a number of levels.

“Behind Veils” is an almost “blasphemous film in the way it criticizes so many aspects of Indian society and the whole system, but Morchhale also manages to keep it light, funny, and entertaining throughout its duration, in a testament to his prowess as both a director and a writer.