Famous for its surreal genre-mashing and cross-gender casting, “Summer Vacation 1999”'s (1988) cultish elements recall the beginnings of shonen-ai (boy's love), one of many queercoded creative spaces that have been veiled for heterosexual enjoyment. Before our time of identity politics and labels, representations of gender and sexual fluidity wove itself into existence by sheer will and unquenchable desire. Today, in the restored catalogs of festivals such as Queer East, we look back in celebration, but also with a mixed sense of wonder, empathy and relief. In Shusuke Kaneko's futurist romantic-mystery, three boys reel from the return of their supposed-dead schoolmate to their countryside boarding school, igniting tensions and unrequited desires. “Summer Vacation 1999” breathes life into a depiction of queer spaces as innocent, fleeting and beautiful, forever scarred into memory.

Summer Vacation 1999 is screening at Queer East Festival

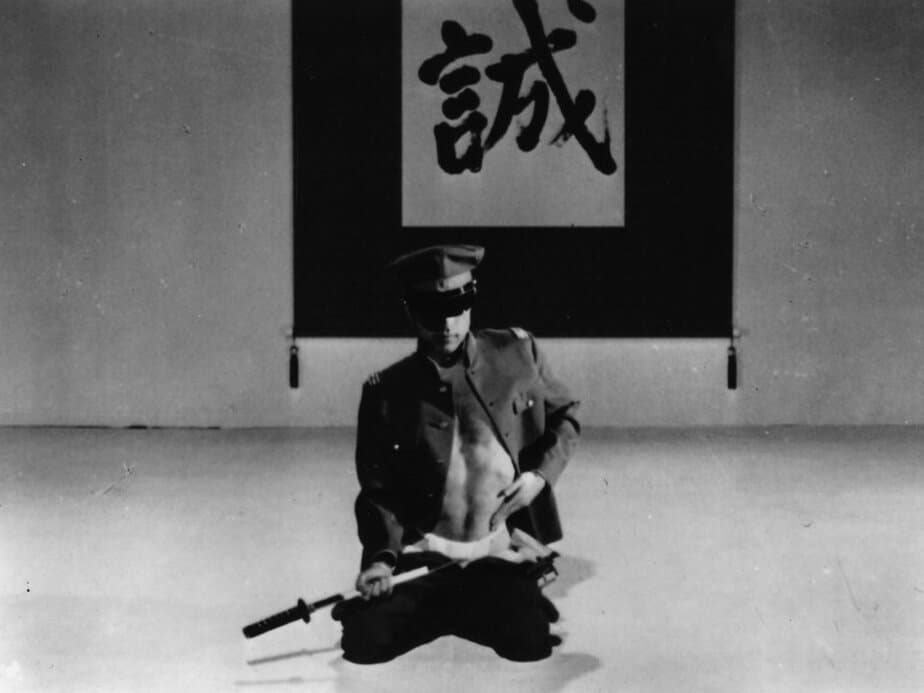

Under an ominous full moon, we witness the dramatic suicide of the well-loved, adorable junior Yu (Eri Miyajima, voiced by Minami Takayama), who leaps off a cliff after senior Kazuhiko (Tomoko Otakara, voiced by Nozomu Sasaki) rejects his romantic advances. Months later, Kazuhiko, his secret admirer Naoto (Miyuki Nakano, voiced by Hiromi Murata) and lonely fellow junior Norio (Eri Fukatsu) are the only students left in their empty boarding school for the summer break. Plagued by guilt-induced nightmares and seizures, Kazuhiko encounters Yu's doppelganger, Kaoru. They are suspiciously identical, but the latter's devious antics such as hunting butterflies and cutting class are a stark opposite from the passive and clingy Yu. Intrigued, Kazuhiko gradually falls in love with him this time, which angers Naoto.

Apart from light sprinklings of sexual aggression, director Kaneko's vision is the definition of quaintness and tragic yearnings. Boarding school romances evoke the allure of classical architecture, cute uniforms and constant close contact. Without teachers and parents, the boys' are free of patriarchal authority and full of angst. Boy crushes are talked about as order of the day. Love becomes less erotic, but a deeply emotional affair underscored by throwing of lily bouquets and lamentations that “I have hurt him too far!” Theatrical and melodramatic as they come, the boarding school compound is a world of intense naivete. A separate, otherworldly dimension to vicariously live through.

Like a hazy midsummer dream, all is lovely but slightly strange. Against the original manga's mid-20th century setting, the film is set eleven years into the future, melding European vintage, AI contraptions and unexplained androgyny. Nothing quite fits together. The Greco-Roman classrooms are intruded by large metal arms clamping down digital computers. Twee piano tracks are accompanied by dissonant ambiences, in particular a repeated train horn that sounds more like a starship gliding in space. All characters are male, but are portrayed by a full female cast, except for Masaaki Maeda and Nozomu Sasaki, who voiced the narrator and Kazuhiko. Altogether, the ‘unconventional fittings' make for a utopia outside of time and space, where pursuing non-heteronormative desires can be normalized and possible. The quintessential queer cottagecore or dark academia (whichever your pick) happily-ever-after fantasy.

In the realm of dreams, “Summer Vacation 1999” playfully defies labels. Is it a gay, lesbian or trans film? The actresses' performances form the undeniable core of the experience. Besides the short hair and uniform, they do not go out of their way to present as male. Once or twice we unexpectedly see the shadow of a brassiere, and the result is a flitting between the binary, in which masculinity and femininity simply coincide and coalesce. Undoubtedly, this brings up questions of how far we perceive gender norms and its associated behaviors. Even in 2024, case studies such as this remain an apt catalyst for discussion. What constitutes acting like a boy or a girl? While the film does not make any political statements, its unbothered existence does broach the question: Why should it matter? Just love, and give it your all!

Watching Norio, the only character without any romantic involvements forlornly observing the rest, we are reminded that these stories are not just exploitative material, but fervent desires of closeted artists and audiences. Loosely adapted from Moto Hagio's “The Heart of Thomas”, the romantic manga signaled shōjo (girl's) manga's expansion to depict gay relationships. BL is often simplified as the objectification of men for heterosexual female consumption, but alternate readings suggest it may also address a multitude of complexities. Girls who want to be boys, who desire access to opinion, daring and autonomy, or who may, as James Welker theorizes with “The Heart of Thomas”, struggle with lesbian denial. Understandably, queer representation is not single tracked. Its history with stigmatization and repression has formed the process of reclaiming your identity into a highly complex one. Genre spaces in Japanese media, such as shōnen-ai (and its lesbian counterpart, shōjo-ai), as well as the sexploitative pinku, with which Kaneko started his career largely operate within the heteronormative, but are designed as fictional outlets for fantasies, where marginalized communities can slip in. And thus, our desires continue to thrive. We remember that we are not alone.

Yet this queer space is still borrowed space, its fragile existence hinging on the demands and validations of a heteronormative market. Coming back to “Summer Vacation 1999”, its most glaring message, intentional or not, is that it is a fantasy. As peaceful as this empty boarding school might be, it will only last these six weeks of summer. And though “it still lives in (their) memory”, as uttered by the narrator, in time the boys will grow up and leave each other. The idea that queer spaces are often transient and temporal very much reflects reality, where most instances of subversion, of ‘embracing forbidden desires' come to exist by chance, in hiding, or in non-traditional forms. In the same way, re-discovering and watching queer cinema is an experience that while deeply validating and formative, will ultimately come to an end.