Despite their seemingly disparate subject matters, “My Father's House” (2011, dir. David Bandurski, Dayong Zhao) and “Lost Course” (2019, dir. Jill Li), two independent Chinese documentaries separated by over a decade, have one important thing in common. Their protagonists all easily fall into the category of naïve dreamers. Nigerian pastors in “My Father's House” and grassroots activists in “Lost Course” believe that, despite the PRC turning more authoritarian with each year, they might have an impact on religion or local politics.

“Lost Course”, overwhelming in its scale and longitudinal approach (the film was shot over the course of six years and then post-produced during the next three), has the feel of a sprawling 19th-century novel. The film captures turbulent local politics in the boisterous village of Wukang, and is framed by opening and closing scenes shot from a fishing boat aimlessly wading through a river. At one point, a character likens Wukang in his speech to a ship. Through these images, paired with the title, the film's central metaphor emerges. Seemingly with no captain helming the boat, the village is condemned to larger political structures shaping its future (although the protagonists of “My Father's House” might suggest Jesus to take the wheel in that case, probably nobody in Wukang would have obliged to listen to that suggestion).

The documentary begins with sequences depicting protests against the village apparatchiks who have sold land which in fact belonged to the farmers. The dispute quickly snowballs to a scale which leaves no option for the politicians but to resign from their posts. As a result, a local experiment in democracy begins. The director closely follows several activists throughout the years, beginning with their participation in protests which would serve as a mythological backbone for their later political careers. Following the protagonist's promising ascent to power via local elections, the story concludes in a somehow Orwellian fashion with several of the characters abandoning their initial idealism and can-do mentality in lieu of a more conformist stance.

“Lost Course's” resemblance to Orwell's “Animal Farm” is so apparent, primarily because of the similar trajectories characters in both stories are undergoing. The film could also neatly serve as an illustration for the ways in which idealist grassroot movements are stifled when faced with the establishment. In the unfolding story, each new fresh idea quickly becomes a stale old one, whilst power and its nature never changes – only the people who wield it can alternate. A somehow Foucauldian reflection may come to one's mind, that power is never possessed by a person, but rather only executed in action. This becomes illustrated in the closing fragments of the film, when coercion is replaced by repression, and threats turn into imprisonments for dissent.

Li's film invites all those nihilist reflections perhaps because of the inevitable nature of the events that unfold on screen. The characters don't know yet how the story will develop. The viewer, however, has a very good hunch that at least some of the revolutionaries will, over time, become revolting. One should also take a step back here and remember a poignant scene, in which villagers hang a poster in English addressed to the international media, recently arrived in search of a headline story. In their announcement, inhabitants of Wukang ask foreign reporters to refrain from using words such as ‘revolt' or ‘uprising': “we support the Communist party, we love our country!”, a statement which only complicates the nuanced political conundrum within which villagers have to operate.

In the most striking segment of the film, when the dissidents start their campaigns, they capture their audiences with appealing phrases about reclaiming the land. It is the most joyous moment of the movie, an apparent triumph of democracy emerging on the back of social upheaval. The plan, however nice it sounds, is vague and lacks any grounding in concrete policy plans. The second part of this 3-hour film proves that, and chronicles the slow descent into the former ineffective governance. Newcomers to the world of politics get played, and their positions in local power structures diminish until they become completely marginalized and finally put in jail. As such, “Lost Course” is an incredibly frustrating piece of investigative-cum-observational documentary, capturing, similarly to “The Transition Period”, absurdities of local governance in the PRC.

An even unlikelier scenario is explored in “My Father's House” by Dayong Zhao and David Bandurski, where a group of pastors led by Ignatius Uwa leave Nigeria for mainland China in an attempt to spread the word of Jesus Christ. Opening with a quasi-prophesy, in which one of the pastors narrates his revelation about needing to go to China, the film sets up one of the more random case studies of globalization – African Christian missionaries attempting to convert the Chinese population. Despite the excitingly ridiculous premise, Zhao's and Bandurski's documentary falls short of depicting the cultural and religious tensions emerging from that unusual experiment.

Clearly a documentary of a smaller scale than “Lost Course”, “My Father's House” consists of a couple of encounters and arguments between the two cultures, often unwittingly comical. A cat-and-mouse game that pastors have to play with the authorities can deliver quite a few laughs. “God blessed me with this technology” admits one of the Nigerian pastors, who, barred from entering China, has to hold masses for his worshippers via Skype. The scene, although absurd, only highlights rather than digs deeper into the nature of the robust opposition of Chinese government to foreigners and cultures they might bring with them. Consisting of small vignettes mixing the domestic with political (as well as pastors' unexpected side gig of exporting female lingerie to Nigeria to finance their mission), the film lacks particular focus. Given its brevity, a meagre runtime of just over an hour, “My Father's House's” erratic narrative feels like an introduction to a larger project rather than a complete work.

However, what ties the two films together are the ways in which two dreams for a change and having impact on the local societies in the PRC slowly fizzle out in the face of a gargantuan state apparatus. For the protagonists of either of the film, their endeavors end with disappointing marginalization, eviction or even imprisonment. The structures they face, with China gearing up before 2008 Olympics in case of “My Father's House”, and a crackdown on grassroots activism during the transition period from Wen Jiabao to Xi Jinping in “Lost Course”, seem unmovable. The two documentaries show how the drive for homogeneous and harmonious Chinese society ultimately prevail when notions of diversity and plurality are introduced.

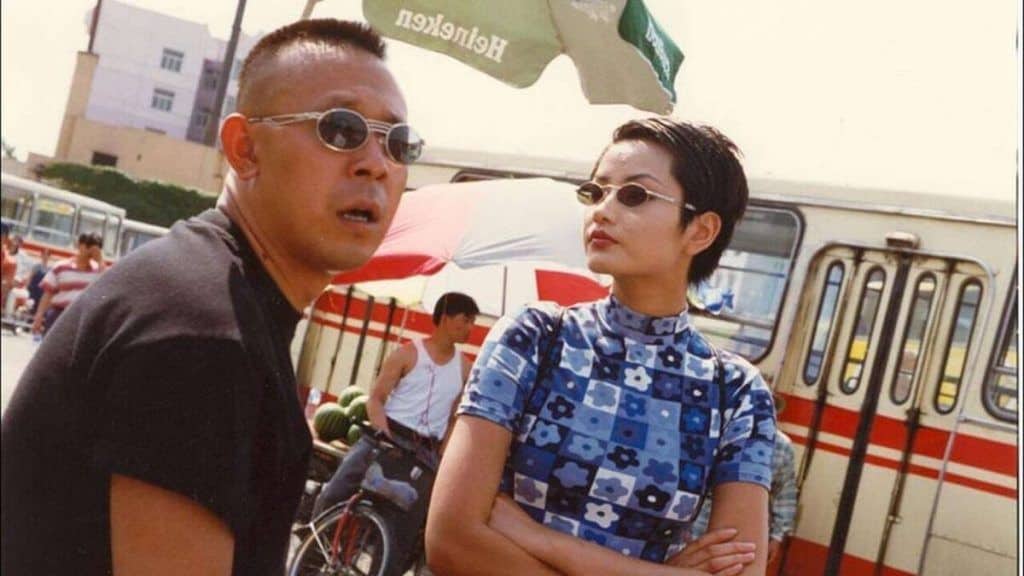

Aesthetically, both projects are examples of the wave of the independent Chinese documentary movement which emerged after the introduction of digital cameras and smartphones. Their rawness is emphasized by improvised, shaky, overexposed and grainy imagery. They are works, with “Lost Course” being a prime example, of militant filmmakers, who capture the chaotic reality unfolding in front of them. Jill Li's film does not shy away from using found-footage recorded by other villagers, further adding a sense of urgency and immediacy to the imagery presented to the viewer. As these two stories prove, plurality and experimentation are not welcome concepts in Red China.