“The Waiting Woman” presents a noble indie effort from writer and director Kei Ota that highlights the complexity of contemporary Japanese middle-aged life. Set in a time of limbo among its characters, the narrative is a dialogue between the themes of love and death. Japan Film Fest Hamburg presented the film for its International Premiere.

The Waiting Woman is screening at Japan FilmFest Hamburg

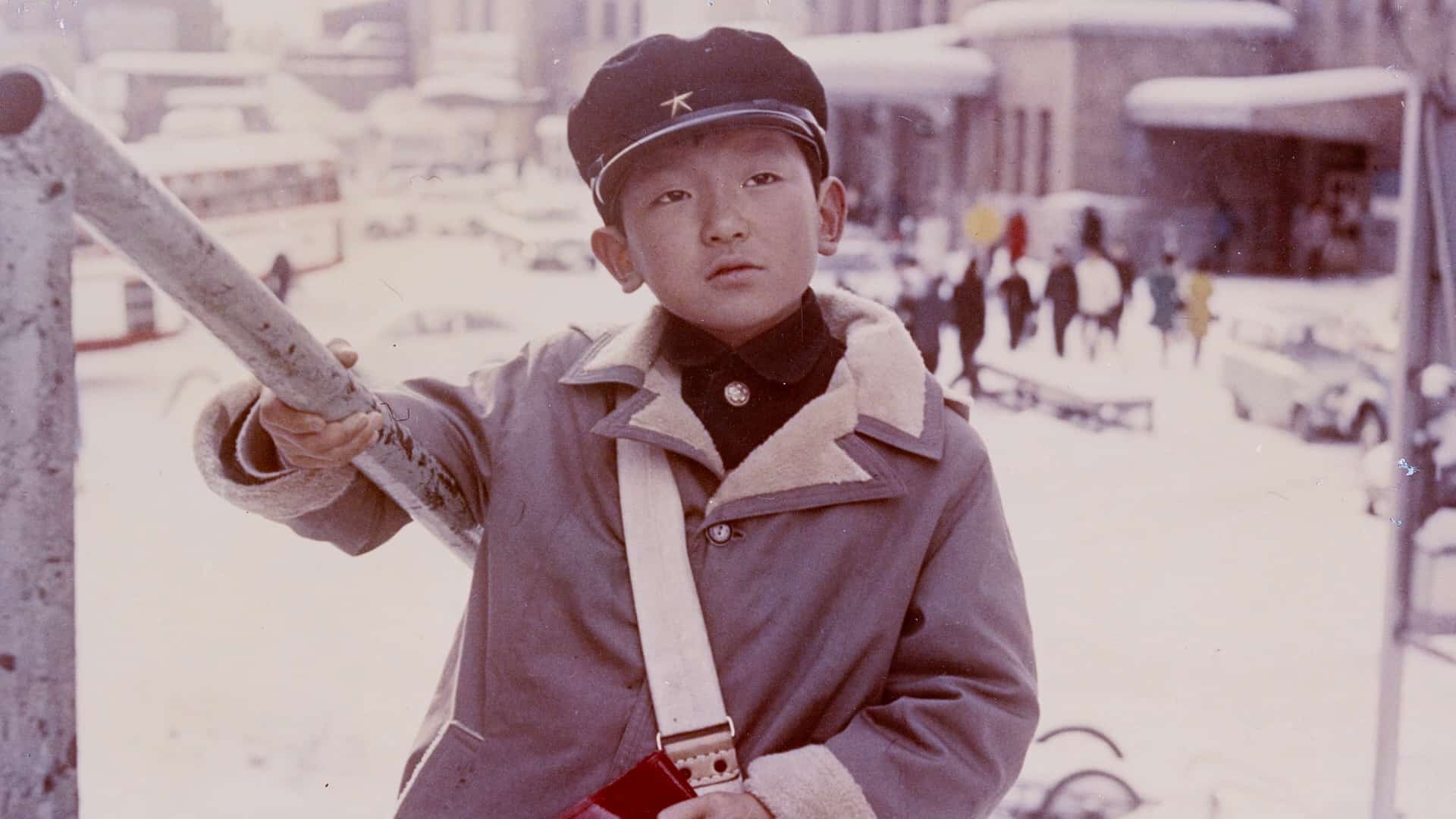

In the middle of his grief, office worker Yasuaki (Kentaro Nagasaki) takes an indefinite leave of absence. However, he does not try to leave his house at all and his solitude takes his mind to unhealthy thoughts as he is being haunted by the memories and images of her recently deceased girlfriend, Asami (Kanami Takasaki). These images and memories show up to him like a ghost. In an attempt to change scenery, he bumps into Misako (Yui Kitamura) who drops a folding knife during the encounter. Yasuaki gets curious over the whole scenario and decides to approach her days later.

As they get closer, Misako reveals that she is waiting for someone who has promised to meet in that same park three years ago. As their conversations get deeper, Yasuaki begins persuading her to stop waiting for whoever she was waiting for and move on.

Check also this interview

What is first noticeable in “The Waiting Woman” is its almost theatrical set up within its dialogue sequences. The exchanges between Yasuaki and Misako often abstracts to universal claims about life and love that they turn awkwardly poetic at some point. But Ota's treatment of those dialogues seems to compliment the personalities depicted by the two main characters, especially when the performances of the minor characters are considered. The two main characters often act around people who are “naturalistic” in their delivery. This contrast seems to highlight the effect of Yasuaki's solitude.

Kentaro Nagasaki's awkward performance compliments his portrayal of Yasuaki before losing Asami, his partner. She often complains about his lack of time spent at home and outside with her. Where his rest days are better spent at home resting than to take Asami out on a date. When Yasuaki loses Asami, his time alone makes him regret the times he should have spent with her.

In contrast to Nagasaki, Yui Kitamura's performance seems flat and unchanging. But this performance makes Yasuaki's efforts to persuade her to stop waiting a great challenge. Misako's character seems to have the fortitude of the enlightened who is always sure of her choices. Between the two, Misako's character seems to play more passively, despite her strong personality as the narrative sways more towards Yasuaki's development.

Another noticeable aspect in “The Waiting Woman” is how much of Ota's directing is polished by the editing choices. While the camera work leaves wanting and the image quality screams indie, the unfolding of the sequences play rather unconventionally that the cuts give more to a psychological effect than to merely open up the next scenes. The scenes cut between present sequences to subjective spaces so fluidly that the dream sequences the film tries to make up seem continuous in the real life of the characters.

This approach to surreal realms makes the initial framing as a ghost story, work for the whole movie and wrap it up as a tale of haunting. Misako is similarly haunted by whoever she's waiting for, and oftentimes scenes from her past cut through her conversation with Yasuaki.

This treatment is not without its setback. The jump from casual conversation between co-workers to pseudo-philosophical exchanges between strangers may seem abrupt and at times unconvincing especially considering the inconsistent treatment to editing that cuts to subjective sequences without warning. It may be a stretch but the treatment is somehow reminiscent of some of the films from Akio Jissoji's “The Buddhist Trilogy” where mundane conversations also jump to philosophical dialogue from time to time. But Jissoji handled his films with care from the first act. Ota's “The Waiting Woman” at times may show signs of impatience and abruptness.

“The Waiting Woman” may look modest in quality, but it obviously has ambitions bigger than the scale of its production. This gesture is enough to be appreciated, especially for an independent production. What is wanting in its technicality and balance, it supplements with its attitude towards the medium.