The second in a series of independent documentaries Noriaki Tsuchimoto shot regarding the mercury-poisoning incident in Minamata, is considered one of the best Japanese documentaries of all time, and has received international recognition. Let us see why.

Buy This Title

As the diary of a case that lasted from the 50's until the 70's is revealed, we learn of a truly shocking story that involved the company and the pollution it caused in the Minamata Bay and the cover-up of the incident that lasted for years. Unsurprisingly, the suppression involved the company, the authorities (the factory chief has served four times as Mayor of Minamata), but more shockingly, the inhabitants themselves, who did not want the rumors about the pollution to destroy the fishing industry in the area.

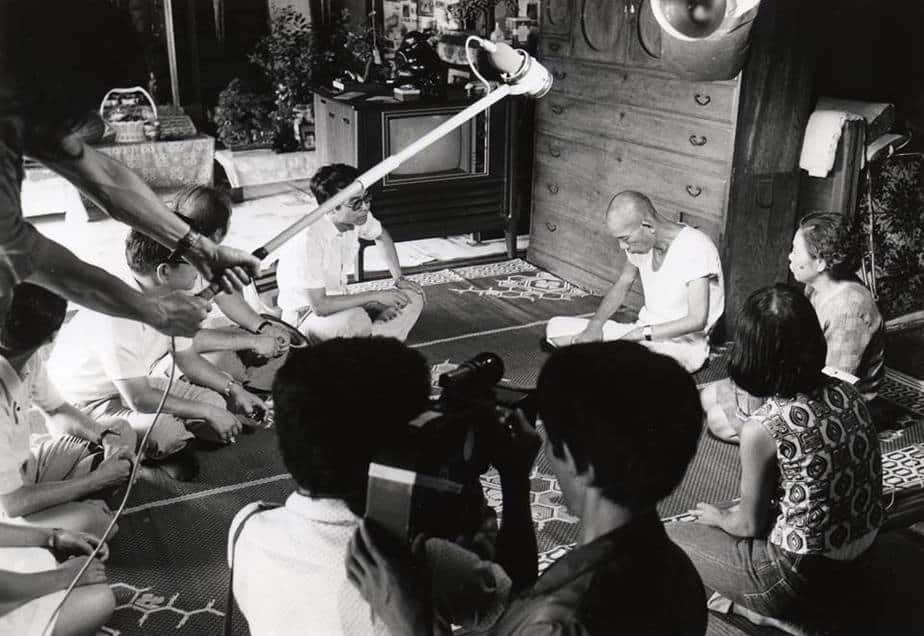

Noriaki Tsuchimoto and his crew stayed in Minamata for five months and filmed an utterly thorough documentary that leaves no aspect of the case in the dark as it unveils a shattering series of events. In that fashion, the documentary includes interviews and footage from the families whose members died of the disease as much as from the ones that have to take care of the victims that did not die but continue to suffer from it, with the children born with congenital disease providing the most heartbreaking images in the documentary.

The interviews with the leader of the initial demonstration in 1958 and the leaders of the committee that was formed to force the company to stop their practices and to compensate the victims are also included, as is the case with the everyday life and the traditions of the people in Minamata.

The first aspect shows their struggles to raise funds to challenge the factory and to finance a research that will prove the pollution, and is the one that actually concludes the film, again in shocking fashion

The second aspect provides another outrageous element, as the victims of the disease had to face prejudice, initially from the hospitals that would not accept them, thinking their disease was contagious and then from the rest of the people in the area, in a series of events that eventually made them pariahs.

Tsuchimoto implements a view as close as possible to the people and the case, which results in a very direct documentary that makes its spectators think they are present during the shooting. In that aspect, Koshiro Otsu has done a great job in the cinematography department, with his camera leaving no detail untouched, as he shoots from a very close distance, particularly during the interviews with the victim's families. The letterbox format gives a retro sense (today that is, since the documentary was shot in 1971) that also benefits the aesthetics of the production.

Tsuchimoto and Takako Sekizawa's editing manages to include as many different footage as possible in the 120 minutes of the documentary (the original cut was 167 minutes and Tsuchimoto cut it in order to screen on festivals and environmental conferences) while retaining a relatively fast pace through the succession of different footage. In that fashion and despite the long duration (for a documentary that is) the film retains a rhythm that does not tire its viewer at all.

“Minamata: The Victims and Their World” is so much more than a great documentary: it is a great spectacle that manages to shed a very analytical light on a case that shocked Japan, and at the same time to highlight practices and consequences, that, unfortunately still keep occurring, in a combination of thoroughness and artistry that deem the title a must-watch.