“So what do you gentleman do for a living?”

“Sell guns by mail order.”

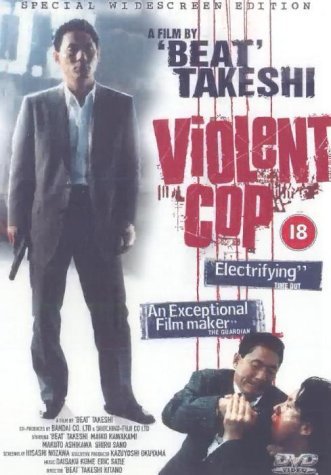

By the time ‘Beat' Takeshi Kitano arrived on the set of Kinji Fukasaku's “Violent Cop” at the end of the 1980s, one could argue the fame of the two men was equally matched. Even though Fukasaku had gained his reputation through his influential body of work, most notably the “Battles Without Honor and Humanity”-series, Kitano was a well-known figure in his home country. Starting his career as a small time comedian, together with his colleague Kaneko Kiyoshi (‘Beat' Kiyoshi), he had become one of the ruling figures of Japanese TV with nearly seven appearances in shows during each week. In between, he had also found the time to act in several movies, most significantly his appearance as Sgt. Gengo Hara in Nagisa Ôshima's “Merry Christmas Mr. Lawrence” (1983).

Ultimately, what started out as a project which would fit the comedian ‘Beat' Takeshi, transformed into something completely different altogether. Since the shooting schedule clashed with Kitano's TV shows, he insisted on changing the overall shooting process, for example, by demanding on one rehearsal and one take for each scene. When Fukasaku found it impossible to work under these conditions, producer Toshio Nabeshima allegedly posed the ironic question to Kitano whether he wanted to take over for Fukasaku. According to Kitano's own account he responded: “Sure? How hard can it be?”

Buy This Title

Whether or not this story is believable or not, fact is “Violent Cop” would be the first time Kitano directed. However, what is most interesting is how the film itself would introduce a new version of the Kitano persona, a new facet of the public figure one might say. Even though the finished product may be flawed in parts, unrefined in others, there is also a noteworthy confidence in Kitano's approach, artistically and technically. Together with the cinema of Takashi Miike, Kitano's work, beginning with “Violent Cop”, would be the logical progression within Japanese cinema. The kind of deconstruction of society and gender, the depiction of violence as well as depravity and passivity Miike and Kitano would establish at the core of their works, advances the kind of work begun by directors such as Fukasaku and Ôshima.

In this essay, we will take a look at the core themes of “Violent Cop” and show how the film fits into the director's body of work. Considering this is the director's first effort, we will see how “Violent Cop” fits into the cinema of deconstruction which Kitano continued in his future works. Naturally, this means this essay will refer to scenes of the film and also other works by the director, so it is recommended to watch “Violent Cop” before reading.

I. A world of violence

It is the face of a bespectacled homeless man grinning into the camera which greets the viewer as the movie begins. The scenery is somewhere in suburban Tokyo, an anonymous grey area where the man has made his temporary home, his belonging surrounding him while he eats something indefinite for dinner. Suddenly, a group of youth appear seemingly out of nowhere quickly coming after the defenseless man, insulting him, tormenting him and eventually beating him until he breaks down.

As soon as one of the young men has returned to the safety of his family home, locked away from his parents in a safe haven of video games and manga, the suburban peace is eventually disturbed again. Azuma (‘Beat' Takeshi) arrives at the scene, quickly making his way past the slightly irritated and worried mother to give the youth a taste of his own medicine. “I didn't do anything”, the teenager cries after several slaps and pushes, as a response to Azuma's demand to turn himself in at a police station tomorrow. Shouting “Well, then I didn't do anything either” the man, who is soon revealed to be a cop, rams the youth's head to the wall, the air filled with the helpless bawling and sobbing of the young man.

Of course, one does not expect a film by the title of “Violent Cop” to be anything but a film which essentially is about violence. The “lone wolf”-figure Kitano portrays is one which experienced viewers soon recognize as a close ancestor to the Harry Callahans and Paul Kerseys, the kind of stereotypes populating the action genre to this day. Naturally, the kind of world we see in the opening minutes of “Violent Cop” is the environment to which Azuma, the long line of corrupt cops, brutal gangsters and other dubious characters are the logical by-products of.

However, one need to take a closer look at the scene and also at its further context. In a movie only slowly revealing missing information to its viewer, only later we get to know Azuma was present the whole time the youth were tormenting the old man. Asked by his superior why he did not intervene and instead followed one of the attackers home, he simply shrugs, saying he did not have any backup. Considering Azuma's stubbornness and general outcast state within the department, one can perhaps safely say he was not interested in calling for backup. Violence is one of the essential foundations of the character of Azuma, so naturally he would rather torment, torture and ridicule the attacker. Since he is a man prone to head-butting, punching and kicking suspects (even colleagues at one point), he rather returns the favor, returning the violence he saw.

At the same time, this “transmission of violence” (Casio Abe) is also met with a certain level of pointlessness. Coming back to the opening scenes, the attack on the old man is a mere act of sadism, of mere boredom by the youngsters, just like Azuma simply acts on his violent impulses as he beats the young man. Both acts of violence serve no clear purpose, and in the case of Azuma only further his reputation as a “loose cannon” among the police department.

In the greater context of Kitano's body of work, Azuma is an early representative of the characters Kitano would play in “Sonatine”, “Brother” or the “Outrage”-series. Disconnected, outcast and increasingly unpredictable, he carries on to completely destroy the self as Casio Abe argues. Since violence serves no real purpose anymore, but is, nevertheless, a defining factor of the world around him, one can either take the road of excess or give up. Kitano's characters have chosen a middle ground: aware of the pointlessness of their violence, they have accepted it, have indeed learned to laugh about it. Death is the only exit possible for Azuma, and he has accepted the reality of it. Not only the meaning of violence is deconstructed, but the character itself as well.

II. The deconstructed cop and his nemesis

One can argue the meaning of the “loose cannon” character is, after all, to be independent of the reality around him or her. Azuma and Kiyohiro (Hakuryu), the cold-blooded hitman, are linked to individual environment only on the surface. While the former's history of violence, disobedience and mental health has branded him an outsider even among his colleagues, the latter's homosexuality and general lack of emotion has made him both a unique asset for his superior, but also a considerable danger, for he acts out of sheer blood-lust at times. Author Sean Redmond even makes a case for these characters also craving for violence to be inflicted on them, accepting as part of the environment or as confirmation of their outcast state.

On the other hand, the instances of the two meetings signify an interesting bond between them, a recognition of the other almost. When the two run into each other, it takes quite a few minutes for the realization to kick in, for Azuma to return to the drug dealer he had interrogated before only to find him dead and his suspicion confirmed. At the same time, Kiyohiro notices how the cop sets a trap for him, a knife placed next to him so Azuma has a legitimate reason to shoot him. Instead he comments on the cop's sister, her damaged mental state and how her brother must be equally crazy, a remark resulting in a violent outburst by Azuma.

Characters such as Azuma or Kiyohiro exist outside the typical attitudes and backgrounds of similar characters. Much like the cop- and gangster-characters of Takashi Miike, they are “ideologically shelterless” as Redmond describes them borrowing the term from Siegfried Kracauer. Since the outside world consists of nothing but violence and corruption, they may just be its epitome when choosing a path of excess rather than adapting fully. Again, death is inevitable for both of them, something they realize and do not run away from.

Ironically, this moment of realization, of their self-destructive nature is a feature Kitano would use again in a scene in his later work “Hana-Bi”. Given the opportunity to shoot him, the killer (again played by Hakuryu) points the gun at Nishi (Kitano) only to put it down after a while. As the two men face each other, there is a strong moment of recognition, of silence between the two of them. Needless to say, their next encounter will mean the end of both of them for both have chosen the road to self-destruction a long time ago.

III. Deconstructing the narrative

If we return to the genesis of Kitano's feature debut, it is noteworthy how the entertainer and trained comedian changed a script which had been written to fit exactly his skills in these fields. Even though there are few instances of comedy still in the finished film, their purpose within the context of the narrative is somewhat irritating, or a window to a much darker kind of humor than one would have anticipated. For example, in one if the longest sequences of “Violent Cop,” Azuma and rookie Kikuchi (Makoto Ashikawa) chase a suspect who has mortally wounded one of their colleagues. Since his young colleague sticks to the rules of traffic, their car falls behind, much to Azuma's frustration who eventually orders him to let him drive. Ignoring stop signs and the desperate pleas of Kikuchi, he manages to find the suspect again, running him over with his car. After the man attacked them again, Azuma runs him over for the second time and – just to make sure – continues to kick the unconscious man lying on the ground, even as Kikuchi tries to cover the helpless man (making him the target for Azuma's kicks).

In order to understand the technique, or rather the kind of comedy Kitano uses. terms such as “slapstick” or “gag” are perhaps mere colors in the narrative and visual palette of the director. The method used here is best described as the equivalent to the kind of comedic routine Kitano had utilized when still being on stage as part of “The Two Beats”. As a repeated “deconstructor” of the reality presented by his partner, he would attack anything from conventions, moral and common sense. In the case of “Violent Cop,” the use of conventions (traffic rules, respect for colleagues and others) is attacked by characters like Azuma working against them. Slapstick, gags and physical comedy are not meant to be funny (even though they are at times), but instead further undermine the conventions of the genre, even audience expectations to a certain degree.

In terms of visuals, especially editing, Kitano repeatedly misleads or undermines (deconstructs) the genre and his characters. Author Casio Abe defines this technique as “discontinuity” within the director's work, one which withholds information to the viewer but also works against conventions. During the chase, Kitano's inserts scenes of two of Azuma's colleagues having a drink while following the suspect, in some cases he uses long takes, for example when Azuma viciously slaps a drug dealer in a restroom. Both scenes confirm the concept of violence Kitano is after (s. I.), but moreover disrupt the narrative, giving unnecessary details while ignoring others. Deconstruction is thus not only a thematic foundation of Kitano's work, or in this case of “Violent Cop”, also a concept which can be found again and again within the other aspects of the film.

Conclusion

Takeshi Kitano's “Violent Cop” may be a film with flaws, but it is nevertheless the work of one of the true auteurs of Japanese cinema, a work of a director who has a unique vision of the world. As Kitano would continue his work with the impressive “Boiling Point” (1990), the theme of deconstruction, of sabotaging genre conventions in favor of a truly nihilist approach might be seen as a logical progression within Japanese cinema. In a society increasingly growing disillusioned with the reality of politics and economics, the notion of a loose cannon digging his own grave is perhaps depressing, but somewhat fitting as well. Takeshi Kitano understands that feeling like no other, and he has found the right images to portray it.

Final note: There are many sources regarding the cinema of Takeshi Kitano. In case you are interested exploring the theme of deconstruction (among others) within his body of work Tristen Harwood's study on some of his films is quite readable. The link to the study is posted below.

Sources:

1) http://www.kitanotakeshi.com/index.php?content=biography, last accessed on: 08/21/2018

2) https://www.imdb.com/title/tt0098360/?ref_=nv_sr_1, last accessed on: 08/21/2018

3) Abe, Casio (1994) Beat Takeshi vs. Takeshi Kitano. Kaya Press

4) Redmond, Sean (2013) The cinema of Takeshi Kitano. Flowering blood. Columbia University Press

5) Harwood, Tristen (2017) A Story in 3 Parts: A Study of Takeshi Kitano's Style

https://www.grailed.com/drycleanonly/takeshi-kitano-cinematic-style, last accessed on: 08/23/2018