“Start again from the beginning.”

Hiroyuki Tanaka, better known under his pseudonym Sabu, admits he sees something of himself, of his experiences in the people he portrays in his films, especially in their philosophy or that of the film itself. One thing is for certain, ever since his debut “Dangan Runner” (1996) the director seems to be just as restless as his central characters, always in motion, either running like the characters in “Dangan” Runner, trotting along while under the influence like the hero in “Monday” (2000) or merely walking along with no particular aim like the main character in “Blessing Bell” (2002).

Buy This Title

In an interview Sabu gave at the Brussels International Film Festival in 2007, he explains how many of his characters live by a strict set of rules, many of which remain obstacles in their way of finding a more meaningful and happier existence. Rules and logic may appear as good when it comes to performing a daily routine like Sawaki, the postman from “Postman Blues” whose life is turned upside down through a series of coincidences and people behaving illogical. However, in the cinematic universe of Sabu routine is perhaps equal to being a mere observer of a more exciting, a happier life one wish to lead. In the end, it takes drastic measures, a night under the influence of alcohol or just a chance encounter with some gangsters in order to set things in motion out of the ordinary, out of control, but also a possibility of showing how much routine can be bend.

“Blessing Bell” is a meditation on life and death, how one might be able to create or experience meaning in the one life given to each individual. At the same time, and quite fitting to the aforementioned points, it is a parody on the nature of routine and human interaction.

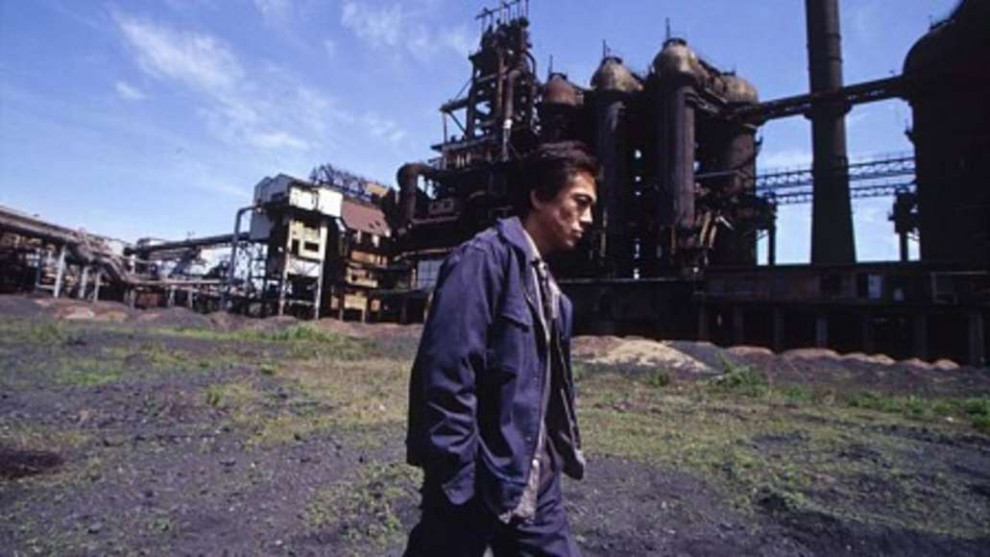

Igarashi (Susumu Terajima) has just lost his job at a factory, but instead of joining his colleagues in their protest at the gates of their former workplace, he starts to wander from the factory grounds to the outskirts of Tokyo to the inner city.

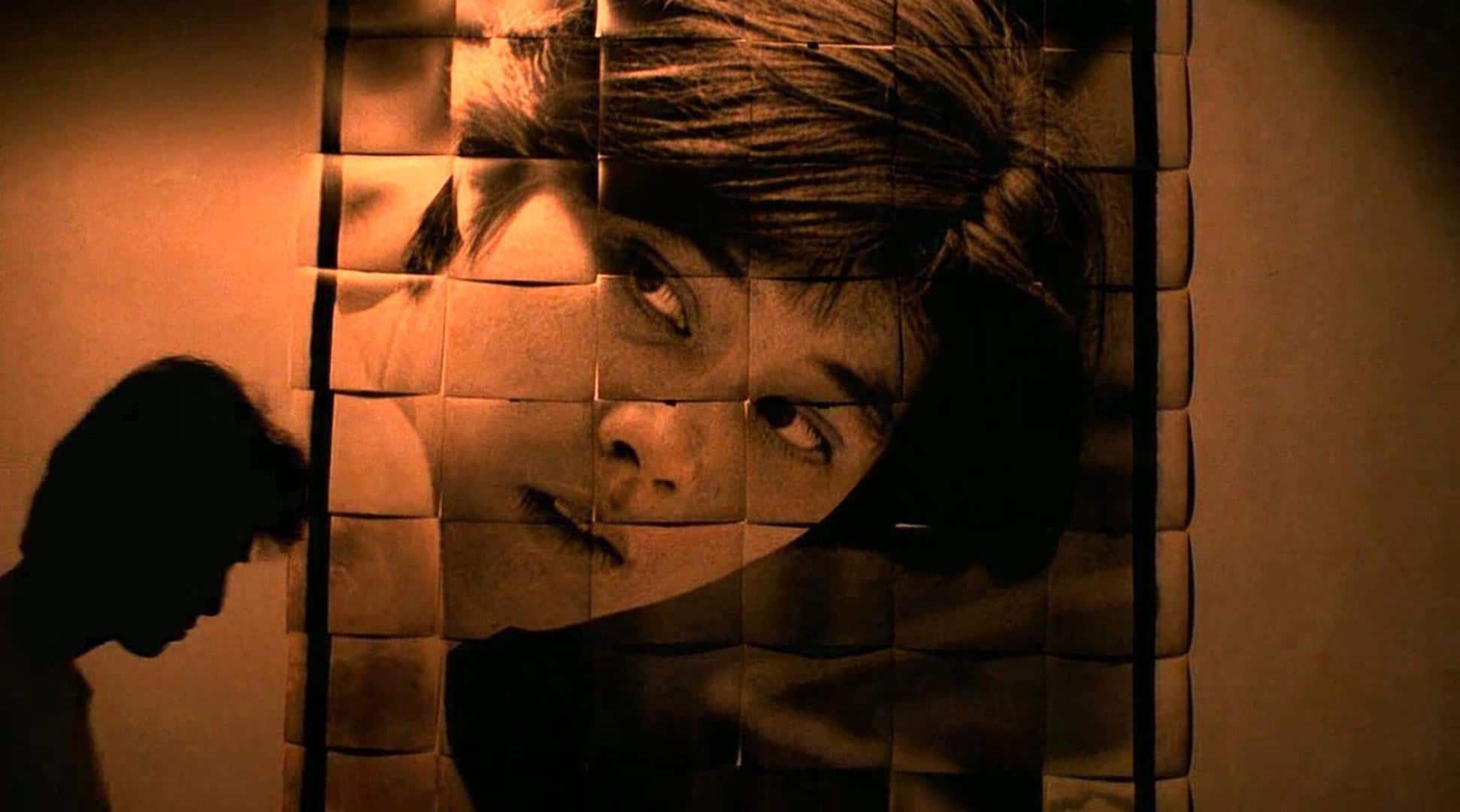

On his journey he encounters various people from all walks of life and experiences strange events, all of them defining an image of these characters and their individual struggles in life.

In one of his novels titled “A Man Asleep” (Un homme qui dort) French writer and filmmaker Georges Perec describes a 25-year old student of sociology does not get up from his bed on the morning of his final exams. He realizes something has broken inside of him, but he is neither depressed or unhappy, he rather does not see the point anymore, convinced he is unable to live, and will probably never (re-)achieve this particular knowledge again. The novel, written using the second person singular, is defined by the introspective bewilderment the young man feels about his life as it has been, an observation he applies as he walks the streets again or sees others later on.

In Sabu's film, Igarashi could be a close relative of Perec's protagonist, even though he seems a bit more positive considering his actions and encounters with others, the latter of which he does not try to avoid; in fact, he can not since encounters rather keep finding him inevitably as he moves on. However, both characters are linked through the modern feeling of having lost a significant connection, perhaps caused by the sudden loss of a job or an internal struggle related to one's purpose in life, predetermined by the choices one has made (or those made by others). The act of sleeping or lying on his bed for Perec's character is devoid of the more pragmatic meaning of relaxation or recovery from the events of the day, but have been reduced to their basics having lost their purpose within the society he lives in.

The act of walking in Sabu's film follows a similar purpose, since Igarashi does not seem to think of something in particular, nor does he wish to give his action any purpose outside of moving one foot in front of the other. There is a scene in which he seemingly engages in a staring contest with a waiting bus, the driver looking at him anxiously through the rear view-mirror, waiting for him to board the vehicle. Considering the bus has a set destination, a purpose for its driving, Igarashi fittingly does not enter and engages further in an activity without purpose.

Sabu's character have a long tradition of being able to find a refuge from their at times dreary lives. Shinichi Tsutsumi's characters in “Monday” or “Drive”, for example, each follow a strict routine see-sawing between a job as a salary man on the one side and being within fixed, at times unsatisfying relationships or living arrangements to which one encounter with life's absurdity, slowly but steadily, puts a permanent stop. Susumu Terajima's character, while also encountering the same absurdity, does not express any kind of surprise, but instead silent compassion and understanding while listening to the existential angst of a dying yakuza boss or the final wish of a terminally ill old man (played by Seijun Suzuki). Even though his ability to listen is occasionally exploited, the overall image Sabu's film creates is one not of a person but of people being trapped in the same kind of aimless walking (or at least that is how they experience it) through life. Masao Nakabori's camera shows Igarashi like the lone hero of a western walking off; however with a lot less purpose and a lot less action. Instead the frame, the relation of person and landscape, seems to favor the latter highlighting his walk into something close to insignificance, into a kind of absurdity he seems to magnetically attract.

In the end, as with all of his films, Sabu's writing highlights a specific view on life, his observations on people and their relationship to the world. From “Dangan Runner” to “Postman Blues”, “Monday” and finally “Blessing Bell” Sabu has deconstructed the protagonist, resulting in the more modern experience of being someone events happen to rather than being the cause of them. Unlike former heroes of his films, in “Blessing Bell” Igarashi expresses neither anger nor frustration for his dire situation without job, without perspective and without purpose. Deemed impotent by circumstance, he embraces the condition on a mission to regain something more important, something internal which has been lost and has just come to realize is not there anymore.

“Blessing Bell” is the combination of what has come to define Sabu's films, a mixture of black, absurd humor while also presenting moments of truth and depth between people sharing their lives for one brief moment. While the “punchline” of his films, as with “Blessing Bell”, might easily be the weakest link in his writing, Sabu is still one of the most interesting directors of Japan, especially because he embraces the absurdity of life like, for example, his colleague Satoshi Miki. In the end, it is all a matter of starting the journey, laugh or smile while you are walking, because sometimes the destination does not matter as much as how you got there.

Sources:

De Vreese, Tom (2007) Sabu & Kaneko (interview)

http://www.filmsalon.be/intsabueng.html, last accessed on: 01/18/2018