A death by suicide is one of the hardest things to process as it sums the excruciating pain of losing someone dear, to the guilt and regret of not having done enough to stop it. Someone may think a lie is a temporary patch. Some would express their feelings in a film. Director Katsumi Nojiri has scripted and directed “Lying to Mom”, a film sadly based on the experience of his own brother's suicide and he has bravely injected it with a gentle humour.

“Lying to Mom” is screening at Nippon Connection

Shockingly, the film opens straight with the suicide of Koichi (Ryo Kase). After a last gaze from his window to the suburban Tokyo landscape, he hangs himself in his room. Even more disturbing is that his mother Yuko (Hideko Hara) is cheerfully cooking while watching a comedy show just a floor below. But Koichi was a hikikomori and being secluded in his own room was nothing abnormal. When the mother discovers the body, she immediately tries to cut the rope in a desperate attempt to save him, but with the sole result of cutting her wrist – in what looks like another suicide – and losing consciousness. Rushed to hospital, she is in a coma, with slim chances to wake up.

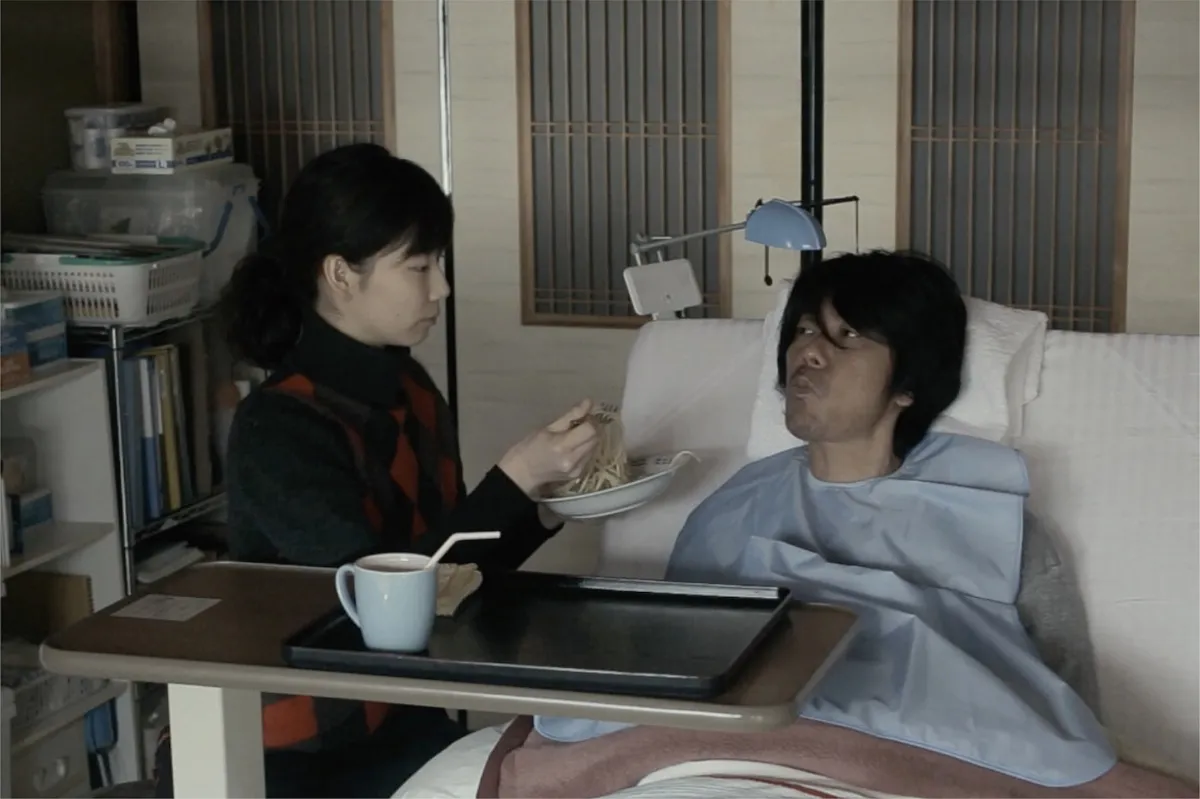

The rest of the Suzuki family need to deal with this huge double tragedy and reactions are very different. Younger daughter Fumi (Mai Kiryu) has always been the judicious one and she feels safe behind a cold and efficient mask, the father Yukio (Ittoku Kishibe)'s reaction is the more bizarre and off-putting of all, but he has good reasons for that. On the other hand, his wealthy sister Kimiko (Kayoko Kishimoto) is already planning for her brother's future, giving for granted that Yuko will not wake up, and Yuko's good-spirited brother Hiroshi (Nao Omori) doesn't lose his positive attitude. But when the unexpected happens and Yuko regains consciousness showing a loss of memory regarding the accident, the shocked family improvises a pitiful lie and tells her that Koici is in Argentina working for the uncle Hiroshi's prawn-import business.

They are honestly concerned she could try again to commit suicide but once their temporary-intended deception is delivered, they find themselves trapped in a net of increasingly convoluted lies to keep the cover in place. Waiting for the right moment to tell Yuko the truth, they construct a very reassuring world in which Koichi not only is still alive, but he is also out of his room and back to an interactive and healthy life. With the help of a Japanese employee in Argentina who handwrites the beautiful letters that Fumi dictates, they keep the conversation with Mum going. But the right moment never comes spontaneously – lies are far too comfortable – until in one of the worst moments the truth is clumsily revealed. Now the real path to acceptance can start.

The focus of “Lying to Mom” is firmly set on the people left behind, as a collateral damage of a suicide, and condemned to float in a sea of doubts and sorrow. Frustrating at times, the film doesn't dwell into Koichi's motives for his extreme act, neither into the mental discomfort that had forced him to shut himself off from friends and family, leaving us inevitably wanting to know more. But at the same time this is a hint – in homeopathic doses, of course – to the pain endured by those who will ask themselves “why?” for the rest of their lives.

Flashbacks show us the failed attempts to communicate with Koichi, the father's hope in science and the mother's confidence in her love. But it wasn't enough. And neither was Fumi's very existence enough for him. Deeply affected and struggling to express her anger, Fumi is the better developed character of the movie, the filter and the eyes of the director. Her intrinsic strength is intertwined with the fragility of adolescence she is abruptly forced to abandon. Everything that is normal routine at her age – like sibling's quarrels – is now a source of remorse and great responsibility on Fumi's shoulders. She is well angry too; being the sensible one of the two, the easy going and non-problematic one means often being left out of the parental attention and create a simmering rivalry that, although normal, in Fumi's circumstances turns very sour. Joining a support group for the bereaved, she shows resilience and reactivity and she slowly learn to share her anger.

Some parts of the film's script are not completely believable, like the fact that Koichi would only write letters from Argentina and never make a phone call, and in my eyes that makes the mother look surprisingly naïve and weakens slightly her character. Also, the subplot of Koichi's mysterious insurance's beneficiary feels a bit forced, like a slightly clumsy attempt to inject a ray of normality in the young man's life.

Nevertheless, the film is a heartfelt tale of reconciliation and acceptance and the light comedic tone helps dealing with an extremely heavy subject matter and show the many unpredictable ways people choose to grieve. Pickling cucumbers included.