Noboru Iguchi is a director and screenwriter. He was born in 1969 and he began his career in the 1990s as a director of porno films. His “Kurushime-san” of 1997, which combined horror and black comedy, revealed his interest in extreme genre cinema. The titles of his next films confirmed this passion – his filmography contains “A Larva to Love”, “Cat-Eyed Boy”, the famous “The Machine Girl” about a girl with an arm replaced with a machine gun, “Zombie Ass” and “Karate-Robo Zaborgar” presented at Five Flavours fifth edition. “Flowers of Evil” is his latest film.

One the occasion of the international premiere of “Flowers of Evil” at Five Flavours, we speak with him about the change of his filmmaking style, Baudelaire, Tanizaki, the concept of the hentai, and many other topics.

During the latest years and particularly your last two films, you have made a change to your style of filmmaking. How did this change occur?

20 years ago, when I was starting my career, I was more interested in indie dramas, films about the relationships between men and women. Then I went into more commercial paths, but films like “Flowers of Evil” is an effort to return to those first movies I did. There are a lot of reasons for this comeback.

Genre films, such as comedies or action ones are often looked down by the audience in Japan. They are simply underestimated and people cannot really appreciate those or treat them seriously as legitimate films.

As a director, I also wanted to follow different paths and direct different films. For that reason, I started working with something more serious, as it was something I had to pursue for the sake of my filmmaking career. “Flowers of Evil” was based on a very popular manga that I personally liked a lot and after reading it, it instantly clicked and I wanted to make a film out of it as soon as possible. Unfortunately, since it was very difficult to finish the film, it took me eight years to close it up.

Why does the film use Baudelaire's book as a base?

Again, because it is based on a manga written by Shuzo Oshimi and it is very much autobiographical. He actually read a lot of Baudelaire in high school himself and this story is about his past. Even myself, I can easily relate to that, since I have tried to read Baudelaire, Bataille or Marquis de Sade. There were actually plenty of people like that in Japan and that is something I wanted to depict in my film.

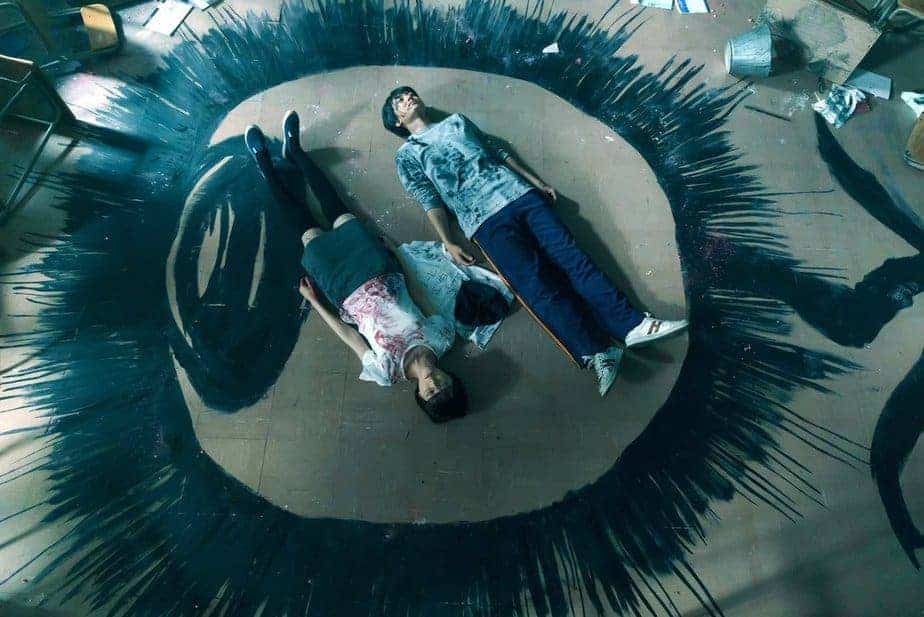

Does the image of they eye has something to do with Battaille?

I do not remember the name of the painter now, but Oshimi was inspired by one who painted a lot of eyeballs (translator's note: he's referring to Odilon Redon, the painting is Guardian Spirit of the Waters). He was so impressed by it, he decided to put that in the manga himself and use that motif of the eye. What he wanted to achieve is that the eye is supposed to represent the evil side of the characters.

The film focuses much on school “politics”. Is the situation presented in school, where the good students are “heroes” and the people who differ from the majority are considered “outcasts” accurate?

In my and Oshimi's generation, there wasn't that much of ‘ijime' (bullying) problem as it is now. In this sense, this school bullying went out of control and became very serious social issue in Japan. Not only students bullied each other, but also teachers became involved in that. It became a very distinct social problem in Japan, very unique for our country. But now its way worse than it was before. ‘Aku no hana' manga was released 10 years ago, but even during these 10 years, I can tell that problems related to education and schools in general are more complex and in simple words – worse. For instance, the phenomenon of ‘hikikomori' is a good example of that. It also increased over the years and I wanted to have that notion in my film as well – that the Japanese social problems we may know about, are worse than before.

The two protagonists are presented as “hentai”. What is the social meaning of the term in Japanese society?

In Japan, many people misinterpret many conceptions or misunderstand one's way of thinking. Many people hide inside the Japanese collective thinking what they think about something that we might as well call abnormality, such as the term hentai may stand for. But recently, I have started to observe that some people became more open to that. I thought that I was a hentai (weirdo) myself and it was something that bothered me. And because of that, I wanted to create something that would be based on that feeling of feeling weird. But what eventually helped overcome that feeling at that time were other films that depicted the reality of not being hentai, but also the persona of Jun'ichiro Tanizaki. He wrote many books that were considered hentai or even pornographic, but eventually they were accepted in the society, so I felt reassured as well, that I am not a hentai myself. In this world of so-called perverts, there are many characters, men and women, who appear and they try to overcome and climb over their problems. I wanted to support that image of that particular struggle as well through my film.

Can you analyze a bit more the concept behind the protagonist of the film?

The protagonist of “Flowers of Evil” is basically Oshimi's alter-ego. On one hand, it is a tale of his past. He reflects himself in the main character and points out what he was angry about back then. Then he strengthens this element through the character's actions. He wanted to depict what happened to him and what he saw back in the day, what kind of people were around him, and did put it into the protagonist. In my case, I could easily relate to that and identify after reading the mange. The protagonist is actually the reflection of me and Oshimi in our adolescence.

Nakamura and Tokiwa, who appear in the manga are actual people from Oshimi's past. In fact, Nakamura is based on Oshimi's wife, and Tokiwa is an ex-lover, and the word ‘shit-bug' (kuso mushi) actually came from Oshimi's wife, when they met for the first time.

Why does Saeki go so far to win Takao? Is it because of love or just because of she cannot accept “losing”?

Saeki is a character that doesn't love Kasuga so much to think about her feelings towards him in a potential future. On the other hand, when she sees Nakamura and him, her pride does not allow her to reject Kasuga, as an act of stubbornness.

It seems to me that Oshimi really likes to depict girls that he did not like, like Saeki, as a representation. As a contrast, he liked Nakamura. Whilst writing the manga, he would say about her that she is cute (kawaii), meanwhile he pretty much disliked girls like Saeki. When I heard that, I asked the actress on the scene to try to be someone she doesn't like; to be this woman, who Oshimi disliked.

Do you agree that small towns like the one in the movie can suffocate the people living in them, particularly the young?

Firstly, the manga was created based on Oshimi's hometown surroundings. We actually did shoot in the same city. I come from Tokyo, which is obviously far from being a countryside city, but where I come from it's pretty much the same, that's why I understand this feeling very well. It's the outskirts of Tokyo, where there is basically nothing happening; a place full of fields and bamboo forests – this is the place where I was raised. These kinds of places exist even in Tokyo area. It is not like we couldn't live there, it's actually easy to live there, as it takes only one hour to be in a huge city, but then again, I felt that I didn't belong there and there are many youngsters who think like that, just because they come from small cities. They are being raised there, but they do not feel a part of it. This is another reason why this manga was very popular, because there were many young people who could empathize with it.

This story had some impact in real life as well. There were at least three cases of demolishing classes and only this year there were two cases of stealing underwear pants in schools, where someone stole at least 30 pairs of underwear.

The scene with them painting the class black is one of the most impressive in the film. Can you tell me a bit about the way you shot it and its significance?

I think this is a very important scene. Kasuga is literally the most common and plain guy. But when Nakamura appears, she starts to bring some craziness in his life, influence his future and destroy what was normal before. Then he starts to become crazy. In this scene, it is the very first time when we can actually witness that – him slowly becoming somewhat mad. In contrast to this film, when people normally read something about madness, they want to read about reflections of people who were crazy, but are not anymore. What I wanted to depict is not the moment when someone is not crazy anymore, but the exact moment when one experiences craziness. Since the story is about struggling through puberty and adolescence, I wanted to show how you come back to normality from this phase of insanity and eventually become an adult.

Same question about the scene where they are about to commit suicide.

This is the moment when their insanity is at its peak and that's why they decide to commit double suicide. There is ta raditional motive in Japanese culture – double suicide (shinjuu). The part when they want to do it, it's not out of love, but because they become closer to death and they want to feel each other through that. This is a very important point for the story but also for Japan itself, because suicides are a huge issue for our culture and the way I see it and wanted to depict it in the film, I think it might be quite peculiar.

We actually had a book published, 20 or even more years ago, which was the manual to a perfect suicide. It was a bestseller. In fact, it actually is a handbook, a manual on how to commit suicide with various techniques and approaches, with very small details. In Japan, there are many people with mental health problems, and thus, there are many cutting-wrists suicide attempts. Even now. When I was in school, I have heard of many people trying to commit suicide. Most of these people are actually young women, it is somewhat very characteristic for Japan. And Oshimi's manga tries to catch this.

Both me and Oshimi, what we wanted to achieve is to highlight these girls who tried to commit suicide, to give them some charm as well. Nakamura is the character that represents it, she is a symbol. I know plenty of people of my age who either really wanted or tried to commit suicide, even among my friends. And the last scene, after the credits, shows that there is some hope, that you can carry on living without actually doing it.

And in my previous films, of course, I showed many actions scenes where people actually die, so it was different, way more different and difficult to depict that kind of vision.

Why does she push him?

It is a very sharp and very important scene. The original scene from the manga is stronger. When we had to reinterpret it from the original, it was not easy. The reason why she pushes him is that she actually wants to let him live, to save him. I wanted to depict her as a gentle, good-hearted person. In Japan, there is a lot of violence in parents-children relationships. If not for the character of her father, I thought that she might not be perceived as a good kid. It is a bit lighter than the manga, as it brings a level of catharsis, but it is also a bit more fuzzy and ambiguous on purpose.

How was the casting process for the film?

That was an extremely tough journey. It got me worried a lot, trust me on that. To choose someone that would fit the protagonist role, we wanted someone who was very pure and unique, but we could not develop that from the actors we've seen. We saw Kantaro Itaro in the other works he made back then and I instantly thought, “that's it, that's him!” Although he is a very proactive, healthy, light-hearted, and bright kid – in fact he's a sportsman – he was able to pull out the performance of a schoolkid fascinated by books. He had something that others did not; an atmosphere that he brought to that character.

Tina Tamashiro, Nakamura's actress is a fashion model, half American, half Japanese. She is very beautiful, far from the image we had in mind at first. My producer told me that she might be too cute for this role, and I started to think about it, but at the end of the day, she was perfect once we met her. When we met her the first time, she had this stare, she was looking at us the way she does in the film, and that was it. Then it was either her or no one.

Nanako's actress, Shiori Akita is actually a 15 years-old high school student. There is a love scene in the film, so I thought we need to have an adult actress. We auditioned over 100 girls, adults included; most of them were 17-20 years old. Nanako is a bit crazy and “dirty” and during the audition, we have seen that she was the only one who could actually do it. What is interesting is that in Japan, non-adults cannot be on set after 8 pm, so we had to run through her scenes until 8pm. It was extremely rapid.

What is the situation with the Japanese movie industry at the moment?

Well, in the case of Japan, we have a budget issue. It is all about big blockbusters or very-very low budget films (e.g. 50 000 000 yen budget films). It is difficult to become a newcomer. You have to start from the very low-budget films and it's difficult to get attention. One of my mentors was Nobuhiko Obayashi, a director who still keeps on making films even though he was diagnosed with terminal lung cancer; he managed to support me and helped me a lot. And that was one of the reasons that kept me on going: his presence and guidance.

Obayashi was actually told by the doctor that all he has left is three months (it was 4 years ago), but he managed to finish his three-hour long film (tranlastor's note: “Hanagatami”). I think it is absolutely amazing.

How was the experience of working with Yoshihiro Nishimura?

We were always together, but then we started to fight all the time. Typically for him, he told me to do my best, but our approaches and techniques started to be on the different pages.

Can you tell us about what you are going to work on, next?

I have a few projects in my mind currently. I thought of extending what I achieved with “Flowers of Evil”, with this bizarre man-woman romantic relationship topic. When it comes to films, I think I have a completely different way of thinking about the medium, maybe a bit weird, but while it still lasts. I want to make films that way. Maybe something in the style of Tanizaki?

I have a strong consciousness about minorities. I would love to make something in style of ‘Freaks' about minorities. For example, I have this idea in mind, to make a movie about Siamese brother and sister. That would be a tale about cultural identity, so to say. She falls for another guy, he has other brother. When there is a kiss scene, it gets very weird.

This interview was made possible with the help of Łukasz Mańkowski who provided Japanese-English translation