“To be deceived is a woman's crime.”

When you listen to the magnificent soundtrack to Quentin Tarantino's “Kill Bill, Vol.1” you will notice that one track called “The Flower of Carnage” sung by Meiko Kaji. Even though you might not understand the lyrics the voice of the singer, the bittersweet melody hints at the character being deeply emotional, full of tenderness, but at the same time carrying something with her, something dark and vicious. It seems to conjure a certain image, feeling or memory of a past and a present of a certain somebody who is addressed in this film, so strong is the voice it wants you to almost take a mental picture of the person, see her pain but also her beauty. To Tarantino this was the perfect sound for The Bride, a character played by Uma Thurman, a woman who has been continuously betrayed and declared dead, but who always endured, came back and finally took her revenge.

Buy This Title

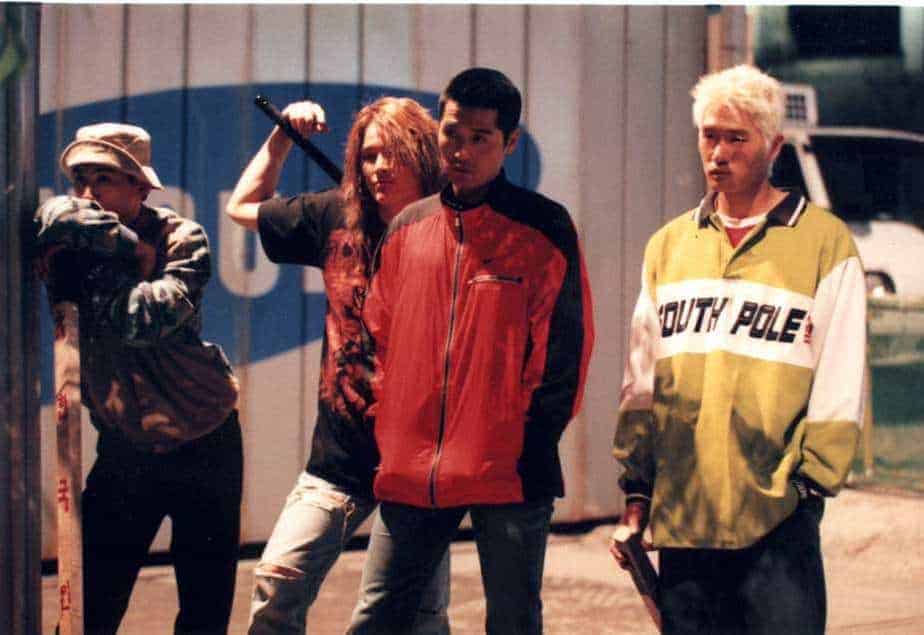

Originally, however, the song was aimed at the portrayal of the character of Nami Matsushima played by Kaji and nicknamed Sasori, scorpion. The film the song was used in was “Female Prisoner #701: Scorpion”, which was based on the manga of the same title by Toru Shinoharu and would spark a series of three more movies as well as countless remakes, an influential movie evident not only by Tarantino's reference to it but also in movies such as Sion Sono's wonderful “Love Exposure”.

In 1970, when the rights to a possible film adaptation were bought by the Japanese company of Toei, the directors gave the material to Shunya Ito, who had been working for them mainly as assistant director for many years, as was the usual career for many directors those days as employees of companies such as Toei. In an interview with Chris D., actress Meiko Kaji points out that working with Ito was quite different, as he would film in sequence and thus film for four months, unusually long since most films at that time were scheduled to about three weeks. He and Kaji also changed the protagonist of the movie who in the manga is a blonde woman who uses obscenities in her language, a trait the actress was not happy with.

Nami Masushima (Kaji) is a prisoner in a woman's jail. She has been framed by her former lover, a crooked cop named Sugimi (Isao Natsuyagi) who has used her affection to make her part of an elaborate scheme of his which involved him climbing further in his career as well as stand in favor with the local branch of Yakuza. As she finds out she has been abused by him she attempts to stab him in front of the police headquarters, leading to her arrest.

In prison, she is the victim of constant abuse and violence from the sadistic male guards led by Warden Goda (Fumio Watanabe). After an escape attempt she and her accomplice, a young convict named Yuki (Yayoi Watanabe) are thrown into solitary confinement, a damp cell, cold and dirty in which they are kept tied and chained unable to move and evade the daily attacks of the guards or the other “special prisoners” bringing them food and using these occasions to further mock them. On one of those times, as another female convict spills hot miso soup on her body, Nami is able to throw her out of balance, leading her to spill the complete bucket of soup on her face. The guards are furious at Nami as none of their usual punishments, beatings and insults seem to work with her, who endures them as well as uses every possible occasion to strike back.

Meanwhile, Sugimi and the Yakuza have worked on a plan to assassinate Nami in prison as the danger of her telling the truth about their scheme is just too great. Consequently, Sugimi gets into contact with Katagiri (Rie Yokoyama), a girl he has arrested himself, and promises her early parole when she kills Nami and makes it look like an accident. Katagiri agrees, but eventually Nami learns about the plot and begins to strike back and take her long-awaited revenge.

On the surface, and by reading the basic plot of the first Sasori-film, one might be forgiven when regarding the film as mere exploitation. For a large part, this is true, since exploitation is what the film aims for with its topics such as sex, the Yakuza, prison as well as the amount of graphic violence it uses with red fountains of blood being spilled and eyeballs being pierced. However, it would be and unjust judgment, basically because “Female Prisoner #701: Scorpion” has a lot more to offer, both narratively and technically, making it stand out among the many films of similar nature which have been made during that time in Japan and elsewhere.

Much like his role model, Spanish-Mexican filmmaker Luis Buñuel, Ito's film aims at deconstructing, especially the images of male and female but also the nation of Japan. During the film, you will see the Japanese flag three times, each time unique in terms of visuals as well as its context. The first time is when the flag is raised with the national anthem in the background being played by a police band and Warden Goda congratulating his guards for their service to their country, as suddenly an alarm bell rings, a prisoner has escaped. As the guards run to fetch their gear and weapons, the certificate Goda was holding in his hand is being trembled upon, made dirty and into a worthless piece of paper. The prison is the nation as a microcosm, exploiting the seemingly helpless and rewarding those cruel enough to beat, torture and cheat their way to the top, with men like Sugimi and Goda as their leaders and most successful specimens. While of course exaggerated, its violence cannot be regarded as a pure entertainment measure like in so many exploitation-films: violence is the founding stone of the hierarchy in the prison as well as the outside world, a system preying on the ones they have declared helpless and inferior. A terrible mistake as some of the men will find out during the course of the film.

The second time we see the Japanese flag is the image of a drop of blood spreading on a white sheet. It is perhaps one of the most memorable sequences as well as its most psychedelic when Nami remembers how she lost her virginity to Sugimi (hence the aforementioned image) and was betrayed by him. Even later on, the corrupt policeman is proud of that moment when he turned Nami “into a woman” as he claims; whether he means the act of sex or Nami's first betrayal by a man is left open. Declared helpless and worthless, easily manipulated by the chauvinistic leading class, women are the victims, the ones to be beaten, to endure. In a way, Nami is the perfect specimen for them as she endures innumerable punishments silently, with especially the latter part antagonizing her male torturers even further. It seems almost ironic, when in one scene, three guards alternate each other in beating and kicking the defenseless Nami until all three of them are completely exhausted while Nami has not uttered a single sound. It seems as if inflicting pain on others for these pathetic men is only “fun” when the victim makes a sound. How truly frightened and desperate these men must be of women that they have sent in three guards to deal with her as she is tied and can hardly move.

The third and final time the Japanese flag appears is near the end, with one of the characters throwing a knife in the air leading to a shot of the knife with the flag in the background. As the men in the film are either stabbed or otherwise terrorized by Nami and her fellow prisoners, not only does the movie fulfill its premise of a revenge-film but also destroys the image of masculinity. The pathetic, grinning savages which are the male characters, as well as their system are ripe for an overhaul and for penetrating them in return for the countless times they have done it to women (at times without their consent). It is a revolutionary image of the knife seemingly piercing the flag followed by the image of the woman leading the new start, Nami, a woman who has turned the tables against her attackers, who has denied them the satisfaction of turning her into one of their helpless, crying and screaming victims.

Ultimately, “Female Prisoner #701: Scorpion” is an impressive first film for director Shunya Ito as well as a great performance by Meiko Kaji turning her character, the angel of revenge with the big black floppy hat and the wide black coat into an unforgettable image. It is a visually striking and inventive film, which – despite its exploitation-roots – has been taken seriously by the people involved in the making of it, an aspect evident in every scene of this magnificent movie.

In the end, we see Nami again, turned into Sasori, the scorpion, just waiting for her chance to strike next. Her fight is not over yet, but we will see her again. Hopefully, soon.

Sources:

Chuck Stephens, “Vengeance is Hers“

Grudge Song: An interview with Meiko Kaji (by Chris D.)