The first film in Ozu's oeuvre shot in colour, “Equinox Flower” depicts the younger generation in a more sympathetic light than the earlier works of the Japanese master. Based on the novel by Ton Satomi under the same title, “Equinox Flower” touches upon the typical Ozu themes of generation clashes and the omnipresent tensions between tradition and modernity.

Buy This Title

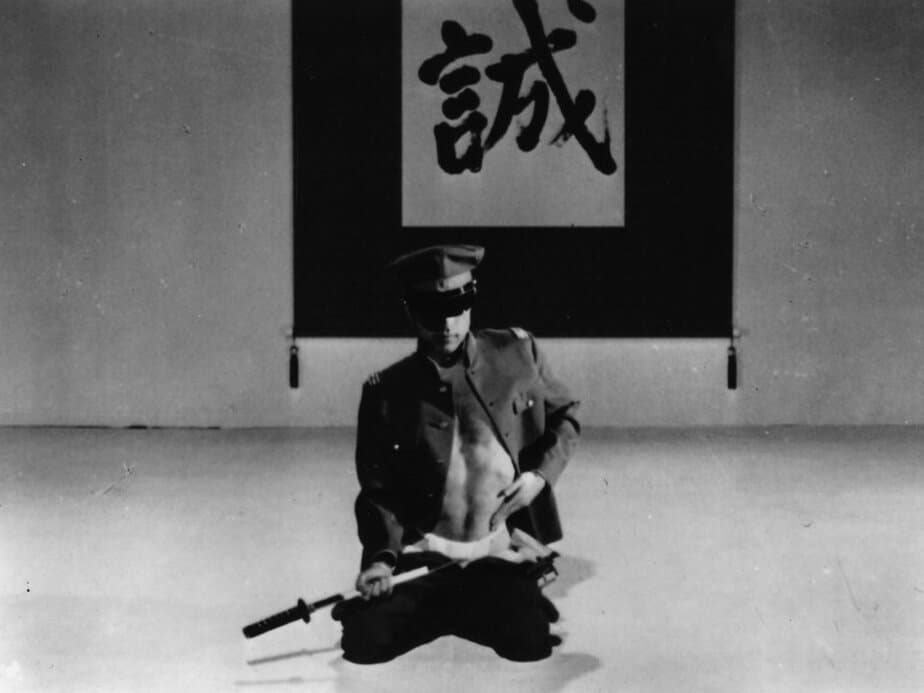

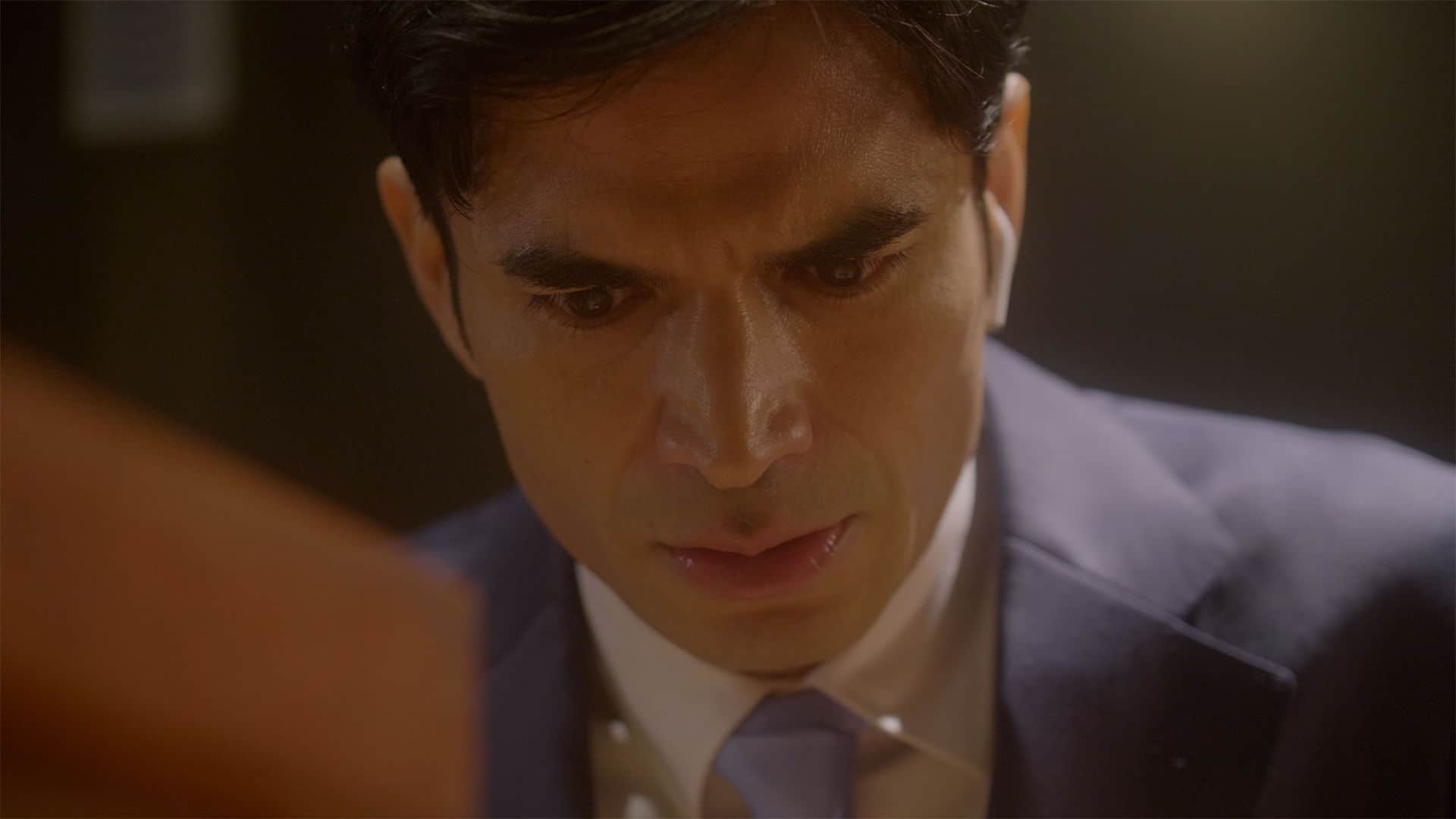

Wataru Hirayama (Shin Saburi) is a businessman who looks for a proper husband for his daughter. In a speech at a friend's wedding, he addresses the issue of arranged marriages. “You are lucky this is not happening in your generation” he seems to say to the newlyweds. Ironically, when later in the film a young man, Masahiko Taniguchi (Keiji Sada) enters his office to ask him for his daughter's hand, Hirayama is conflicted, to say the least. Because Hirayama didn't get to choose his daughter's husband, but is rather presented with a candidate, his position as the family's patriarch seems to be undermined. Plus, it runs against the traditional order of things.

After that incident, we follow Hirayama as he goes through an internal struggle between his principles and personal wishes. The viewer watches the protagonist slowly come to terms with the generational change. Ozu illustrates, with a large tinge of humour,the father's double standards when it comes to the freedom of his daughter. The director thus focuses on the point of view of the elderly as something dated.

As mentioned above, Ozu is in safe waters here. By focusing on the gentle family drama, the director once again comes back to universal conflicts between the New and the Old. The first forty minutes of the film are told in a chaotic, yet slow-paced fashion. Ozu jumps between characters and subplots to create a microcosm of the Hirayama family. Yet, the plot actually thickens from the moment Taniguchi opens the door of Wataru's office. From then on, all hell breaks loose for the protagonist.

The film opens with some establishing shots of a railway station, and ends with a sequence of the train, with Wataru on board, driving away from the spectator. Thus, although the film may feel static in its cinematography, editing and pace, it does create a sense of journey with the protagonist, who has to discover fallacies in his thinking. It is further emphasised by Shin Saburi's charismatic performance as Wataru. He adds a degree of levity and seriousness to his character, whilst remaining very humane and likeable.

What will strike the viewer the most is definitely the evocative usage of colours by the cinematographer, Yuharu Atsuta. Colour was a novelty in Ozu's vocabulary in 1958. The film's eponymous flower is more commonly known in English as hurricane lily, and is famous for its red colour of the petals. Legend has it that if one sees a particular person for the last time in their lives, higanbana flowers would bloom on the sides of the road. This of course refers to Setsuko's departure from Hirayama's life. Ozu and his cinematographer play on this symbolism through the lavish usage of the red colour. Thus, most of the scenes seem to contain some red elements as reminders of Setsuko slowly slipping away from Hirayama.

“Equinox Flower” is an interesting entry in the filmography of the Japanese director, as colour seems to add a certain freshness to an otherwise mundane and typical Ozu story. It depicts an interesting moment of social shift in the customs and traditions of 1960s Japan, as “Equinox Flower” shows the rebellious youth willing to break away from the past represented by their parents.