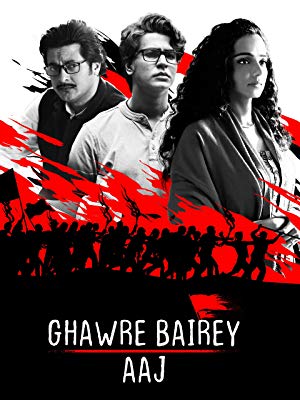

Aparna Sen's adaptation of Rabindranath Tagore's classic novel ‘Ghare Baire' (Home and the World) has a contemporary setting, in as much as the glimpses of nationalism that were present in Tagore's novel have now taken an uglier, bolder and – if one might say so – more urgent shape in the film. As all artists must do, Sen alludes to a number of ongoing issues of conservative supremacy in India, and chooses to use merely the structure of the novel as her source material. Which is good. Which is relevant, and the need of the hour. Which is exactly what one would and could do in setting the story in modern times. Which is why the film finally works, despite some flaws in its writing that cannot be ignored. The film is a statement of protest first, and an exploration of themes such as faith, adultery and guilt much later. Somehow, while watching the film, therefore, I felt that it lost this fine balance on a number of occasions.

Watch This Title

Nikhilesh is the executive editor of a news publication, living and working in the nation's capital, Brinda is his wife. Sandip is an old friend of Nikhilesh. Once a fiery and hot-headed left liberal, Sandip has gone through a traumatic experience which has turned him into an orthodox right-winger who will stop at nothing to achieve his and his political party's ends. Being more enlightened, compassionate and broadminded in his outlook, and not one to let politics come in the way of friendship, Nikhilesh welcomes Sandip with open arms when the latter decides to come and stay with him. But as the wily Sandip begins to work his magnetic charm on his friend's somewhat vulnerable wife, tension begins to arise.

It would be unwise to draw parallels between Sen's adaptation and that of the famous adaptation of the same novel by Satyajit Ray. Which is exactly why I shall avoid it in my review. A protégé and close associate of Ray, Sen has developed her own unique style, distinct from that of the master, and that is a choice that we must all commend. However, comparisons to her source material are both unavoidable and just, and it is in that context that I must say that she has not only captured the very spirit of Tagore's message in her film, but has at the same time gone on to give it a credible, germane and – most of all – essential twist, both in terms of context, as well as storytelling.

Consider, for instance, the Dalit tag that Brinda just cannot seem to escape the shadow of. One might ask – is there a sense of gratitude that dwells in her mind, for being accepted as an equal companion for life by her husband? If yes, does this sense of gratitude lead to a sense of guilt when she gives in to the lure of adultery? Is her anger, then, a corollary to this guilt – a sort of denial of the irreparable harm that she has advertently brought upon the establishment of spousal faith? Notice how all this is connected with her Dalit identity – a clever twist to Tagore's characterization of the story's heroine.

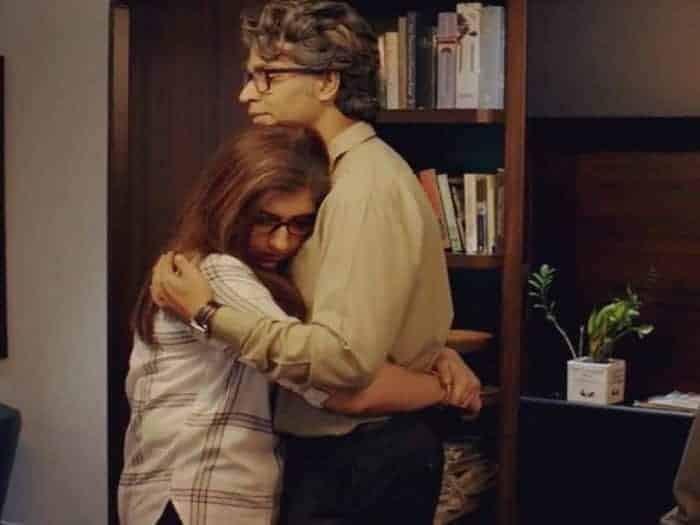

Consider, also, the character of Nikhilesh – one who understands the true plight of the neglected and the downtrodden section of the society once he comes face to face with them. It is this experience of his, this knowledge of being the possessor of good fortune in a land of the impoverished majority, that makes him humble. Humble, mind you – not meek. For it is the same experience that makes him aware that crimes against marginalized minorities are to be dealt with by those who can – men such as him – especially when such crimes are state-sponsored. This humility, however, has a rather tragic consequence in his personal life. In a beautifully written and easy-to-miss scene from the film, his wife confronts and accuses him of never speaking his mind with enough conviction – a fault that she does not see in the intense, assertive and passionate Sandip. At this point in my review, I would like to take a moment to pay my respects to Tagore, whose timeless creation stands relevant even today, and to Sen for interpreting it in a manner so beautiful as this one scene from her film.

Sandip, on the other hand, is the devil personified – robed in the impeccable attire of decency, and skilled in the high art of seduction. His beliefs are strong though – how else does one condone the murder of an innocent human being? As I was ruminating on the film much later, I wondered, though – how did this seemingly inexplicable change come about in him? How did the aggressive foot-soldier of anti-establishment student politics in JNU turned into this suave and ruthless right-wing nationalist? Sen offers an explanation, which did not work for me at all. It seemed like too far-fetched a notion, and I could not bring myself to invest in it. Having said that, it is undeniably true that at the heart of this undesirable and tragic shift in beliefs is once again – politics.

That is the essence of Sen's film – politics – and it is in this aspect that her adaptation differs from the work of Tagore. To put it in simple words, Tagore's work focuses on the frailty of human relationships, and uses nationalism as the context of the story. In Sen's interpretation of the novel, she seems to focus an inordinate amount on the political upheaval of the nation, so much so that it comes dangerously close to overshadowing the human story. This choice may have been personal, but there is no denying that it does impact the artistic value of the film.

The performances are excellent though. My choice among the three is, without a doubt, Anirban Bhattacharya, who is absolutely flawless as the all-forgiving Nikhilesh. I say this, mind you, not out of sympathy for his character, but entirely on the merit of Bhattacharya's performance. Jisshu Sengupta gives us a credible act, and his success lies in the fact that he manages to infuriate his audience with his vile motives, while coming across as dashingly charming at the same time. Not an easy character to play, but Sengupta pulls it off quite well. Tuhina Das plays Brinda – who I personally consider the central protagonist of Tagore's novel. Once again, a very difficult character to play, but she does very well. I have a feeling it would be unfair to say that Sen extracted a wonderful performance out of her, for there is a natural earthiness to Das that seems to have helped her in her portrayal of the earthy, vulnerable Brinda. Among the supporting characters, I quite liked the role of Nikhilesh's college friend, played by Sreenanda Shankar, who beautifully depicted a strong and natural bond of friendship and feminine instinct – in stark contrast to the so-called textbook version of friendship that existed between Nikhilesh and Sandip.

The cinematography by Soumik Halder is good, as is the music by Neel Dutt.

As for the writing, I liked the overall treatment that Sen has given us, but along with the aforementioned qualms I have, I must also add that the climax of the film does come across as a bit too masala for my taste, but my conjecture is that it comes from a place of anger and frustration, rather than from one of artistic tranquillity. As I said before, politics weighs a bit too heavily upon Aparna Sen's ‘Ghawre Bairey Aaj'. It may or may not have been avoidable. But it certainly shows.