In 1945, at the end of World War II, the United States and Russia divided the Korean peninsula into two. The Russian supported North remained “Joseon”, the original name for the country as a whole while the US-backed South renamed itself to “Hanguk”, thus creating a divide between people that have otherwise the same language, ancestry and roots and who should otherwise have the same rights to the peninsula as a whole. Ever since, the two countries have been at loggerheads, a peace treatise following the Korean War in 1953 only existing in name. The propaganda machines for both countries have since been eager to call the government and the people of the other the cause of the problem and the obstacle standing in the way of a complete reunification.

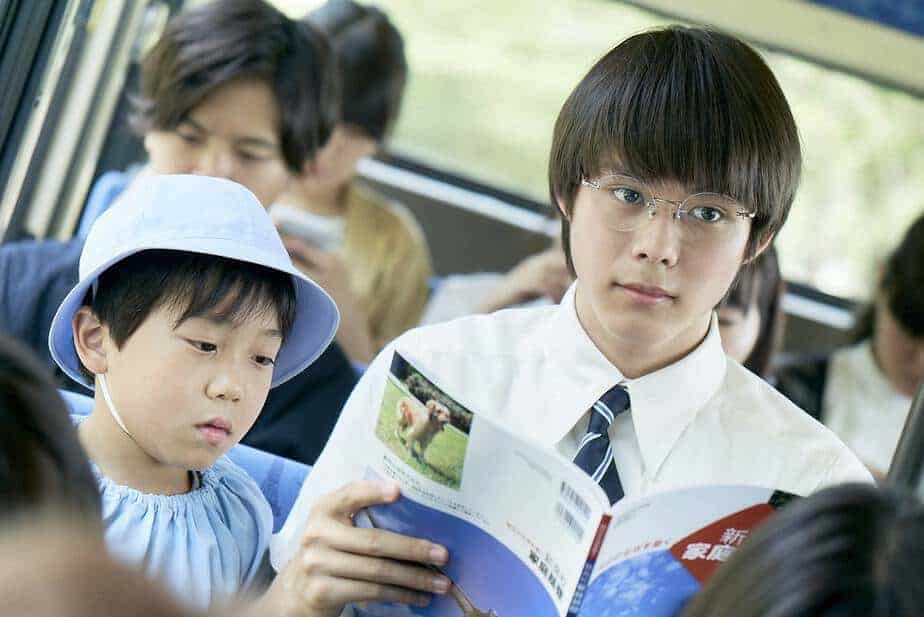

Ever since his school days, director Jero Yun has been taught, just like his classmates and every other student in the country, to sing proudly for a reunification, while also being told that their Northern compatriots are horrible people. Living in the South, access to information on the North or North Korean websites is just as much censored as South Korean websites are banned in the North. But when he moves to France for studies, he is able to freely access these sites and information, at which point he realises that propaganda exists on both sides. Each side is being portrayed as the villain by the other to their people. Putting politics aside, it makes him wonder just how bad can people who are essentially of the same blood and heritage really be. Can a man-made border really change people this much? The only way he can truly know the answer to this, he figures, is to meet some North Koreans himself. Being a South Korean himself, this proves easier said than done, as Yun finds out when he arrives to cities of the China-North Korea border in hopes of meeting North Korean refugees, risking his life and freedom in doing so.

Yun spent the first half of 2011 in China, trying to meet North Korean refugees, people he calls his “enemy brothers”, who are sure to be residing in some border cities. While initially unsuccessful, he was able to ultimately meet with four individuals, interviews with who form the crux of his film “Looking for North Koreans”, three of who were in China while the last back in Busan, South Korea. The three interviewees in China include a North Korean prostitute, a housewife who was sold on her arrival in China and a South Korean man with a North Korean wife who was, at the time of Yun's interview, kidnapped by a Chinese gang. The prostitute's story, in particular, is successful in establishing just how similar the two people are, liking singing, dancing, watching musicals just like everybody else. It's just that the North Koreans get to do it within the stipulated government rules, singing only the songs they're allowed to and enacting musicals that tell the stories of their great leaders and their policies.

These paint a truly tragic story of those that even manage to escape North Korea. The women, in particular, get the short end of the stick, with both the interviewed women being sold into prostitution. Without official papers, refugee status or money to buy a way out, they get endlessly exploited, with no hopes in sight. Despite all that, they are, at the end of the day, normal mothers and wives like any Yun would meet in his own country. The story of the innkeeper couple, a South Korean man and a North Korean woman, is equally fascinating. As Yun headed out to meet them, who had been helping smuggle people in from North Korean and housed them in their inn, he found out that the wife has been kidnapped by a Chinese gang, taking advantage of desperate refugees and the husband was trying to raise money to have her freed. Their story feels like something out of a movie and, if it didn't transpire right in front of the camera, one would be hard-pressed to believe as truth. But that is the reality of these refugees. Life that otherwise seems unbelievable is lived by them day in, day out.

The final interviewee is a well-educated gentleman who Yun met after returning to Busan. This interaction, in particular, feels most emotional and personal as the man talks about his parents that he left behind and has to live his life without knowing their fate. Sure, he made a life for himself in the South, but the cost of it was too high to ever truly make him happy. Apart from the interviews, there's some additional images that prove interesting. The raw footage of refugees being caught by Chinese officials to be handed over to North Korean government, as the refugees desperately try to break free from what is evidently going to be a very short life back in the North, is truly heartbreaking. The part where he takes a boat as close to the North Korean waters as he can and shoots normal people going through normal life, through binocular,, so close yet so far that he can never get there, also evokes a keen sense of longing and melancholia. Yun's calm and soft narration furthers that feeling.

Like with a lot of things related to North Korea, “Looking for North Koreans” also ends up being an eye opener. Where most documentaries focus on life in the hermit country, Jero Yun is more interested in the people from there, his “enemy brothers”. And the people in his film have a fascinating tale to tell. You really wish that these people, particularly the innkeeper couple, had a happy ending of their own. Until they do, one can only stand along singing the reunification song.