8. Heart Blackened (Jung Ji-woo, 2017, S. Korea)

Jung Ji-woo has had a varied oeuvre, including a family drama, love stories, a politically charged drama and a sports film, but this is the first time he handles a thriller and, for the most part, succeeds at it. The film works best as a whodunit, as Hee-jeong slowly unveils the events of the night with the help of eyewitnesses and surveillance footage. One might wonder if a lawyer would go to such extents to get to the bottom of a case, but her motives to clear her friend's name are understandable. Tae-san's efforts, on the other hand, seem completely believable from a man for whom money is nothing but means to an end. The involvement of all parties in the events of the night keep changing and keep the viewer guessing. (Rhythm Zaveri)

9. Innocent Witness (Lee Han, 2019, S. Korea)

Superstar Jung Woo-sung takes a backseat and lets young actress Kim Hyang-gi drive this feature, about a lawyer wrestling with the idea of putting an autistic witness case. The film's understanding and portrayal of the stigmas associated with and the hardships faced by those with mental illness is commendable. While the central mystery may not be too unpredictable, it plays second fiddle to the developing friendship between Jung's Soon-ho and Kim's Ji-woo, which takes the story forward. Jung Woo-sung is effortless as always but it is Kim Hyang-gi who deserves all the praise for her nuanced performance. (Rhythm Zaveri)

Buy This Title

10. The Third Murder (Hirokazu Kore-eda, 2017, Japan)

Hirokazu Koreeda's effort to stray away from the various versions of the family drama, was, once again, crowned with success… although Koreeda has perfected the style of the Japanese family drama, I found that he was repeating himself in his last movies. Thus, this turn to a different theme, genre, and even format since “The Third Murder” is shot in Cinemascope, which he has not used before, is more than welcome. (Panos Kotzathanasis)

Buy This Title

11. Verdict (Raymund Ribay Gutierrez, 2019, Philippines)

An entry for Orizzonti Section at 76th Biennale di Venezia from the Philippines, “Verdict” unfolds the overwhelming picture of domestic violence and its aftermath in the form of legal injustice. This is a story of a family of three: Joy and her six-year-old daughter, Angel, and the head of this not so lovely household, Dante, whose role of a father includes coming back home drunk and beating his wife and daughter brutally. They live in Manila which is a place that Gutierrez pictures as a hell on earth – not through a literal representation of violence, but rather with a convincing disbelief of what is happening in the Filipino bureaucracy, or maybe for that matter: bureaucrazy. The absurd theatre of the street-court that serves as a place for the domestic violence case is filled with claustrophobia and drains all the emotion from the audience, leaving them with an immense doze of repulsion. Surely, the legal court has long forgotten how to serve justice to the people, just as it seems Manila will forget the sake of Joy and Angel, simply because the capital of the Philippines seems to be no place for angels, no place for any joy. Gutierrez's take on Manila's domestic violence grasps perhaps the most prevalent form of abuse in his country, but he is not only revealing the bruises on women's bodies, but also the stains on the side of those, who legally are supposed to take the side of abused ones. (Lukasz Mankowski)

12. A Wife Confesses (Yasuzo Masumura, Japan, 1961)

One of the least known titles coming from a Japanese New Wave representative, as well as a director known for his pinku-like adaptations of Tanizaki prose, Yasuzo Masumura, is a rollercoaster close-up of a woman tortured by the patriarchal world, both of men and legal structures. Bravely played by Ayako Wakao (Masumura's favorite actress of all time) in “A Wife Confesses”, the heroine represents imprisonment in Japanese social rights-and-wrongs. The film is almost entirely shot in the legal court and the case revolves around the alleged murder of a husband committed by his wife (Wakao), who had an affair with the husband's approval. Masumura's great effort encapsulates the inability of a woman to clear her name, as he keeps framing her within the matter of ticking time, her gestures of helplessness and inaudible acts of despair that prove the uncanny unerringness of Japanese patriarchy. This is a story about a woman who has never had a breath to shout strong enough, with one of the most heartbreakingly condensed finales of the entire Japanese New Wave Cinema. (Lukasz Mankowski)

Buy This Title

13. Death by Hanging (Nagisa Oshima, 1968, Japan)

“Death by Hanging” is a unique film, both for its context and presentation, but also as the embodiment of Oshima's ideas regarding both society and cinema. A true classic. (Panos Kotzathanasis)

Buy This Title

14. Juror 8 (Hong Seung-wan, 2019, S. Korea)

“Juror 8” is inspired by the first ever case in South Korea to be overseen by a jury back in 2008. Think of a Korean “12 Angry Men” and you wouldn't be too far off, but this film features a much lighter tone to the Lumet classic as, like many good Korean dramas, it manages to effortlessly blend many moods together. It's not all laughs and giggles thought, as the film touches important themes like class and the perception of those with limited mental faculties by society. The brilliant ensemble case, led by the ever-reliable Moon So-ri as the headstrong presiding judge who doesn't think much of the jury concept and the charming Park Hyun-sik, makes the film a lot more enjoyable than it already it. (Rhythm Zaveri)

Buy This Title

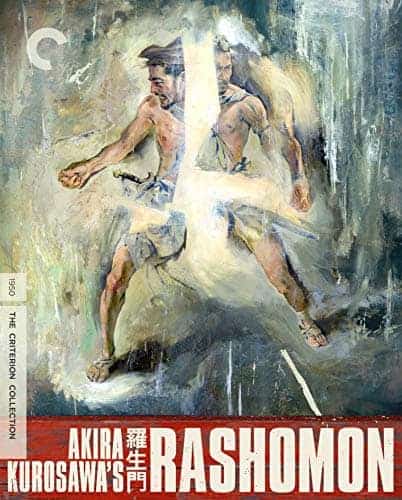

15. Rashomon (Akira Kurosawa, 1950, Japan)

The visual style gives meaning to each sequence. Take, for example, the scenes in the court. The setting looks extremely pure, in an open and well-lighted space where even the sand seems to be smooth, as this is a place where justice rules. On the contrary, the scenes in the forest are filled with shadows, and even the small amounts of light find it difficult to pass through the thick branches. This depiction symbolizes that the forest in the story is a place of lawlessness. (Panos Kotzathanasis)

Oh My God made the list but no Pink?