“Fabricated City” is Park Kwang-Hyun's long overdue follow-up to his smash hit and award winning 2005 war comedy “Welcome to Dongmakgol,” which on its release was the fourth highest grossing film in South Korean film history, coming second at the box office that year just behind Lee Joon-ik's “The King and the Clown.”

“Fabricated City” screened at the New York Asian Film Festival

Just his third film, “Fabricated City” keeps the humour of “Welcome to Dongmakgol” but trades the war time setting for a contemporary one, and the conflict between North and South Korea for that between youth and adults. The protagonist, Kwon Yoo (Ji Chang-wook), spends his days playing online video games at an internet cafe (baang) as the leader of a virtual team combat unit named Resurrection. In his online life, Kwon is a hero, placing his avatar at risk in order to save his virtual army. In his offline life, Kwon is unemployed and lives at home with his devoted mother (Kim Ho-jong). One day, Kwon receives a phone call from a young woman who asks him to return her cellphone which she left in the internet cafe. Confusing his offline persona for his online one, Kwon is all too happy to accommodate a damsel in distress. However, the phone call is a set up and Kwon finds himself arrested, charged with rape and murder, and locked up in a high security prison for the rest of his life. Brutalized by the other inmates, Kwon's only hope of survival is to escape and discover the identity of the real killer in order to clear his name. However, he will need the help of his virtual army in order to do this. Will Kwon and his team transform from virtual to real-life heroes?

There is a great deal in the news about gaming culture in South Korea, most of it negative and is centred around the discourse of addiction. As a gamer, Kwon is the epitome of the shut in. Fears around the damage that online gaming has on young people led to the Cinderella or Shutdown law of 2011, whose aim was to prevent children aged 16 and under from gaming between 10.30pm and 6am: although this law has been amended since its implementation. Classified as loners and misfits, online gamers are seen as the equivalent of drug addicts, alcoholics and gamblers and therefore a threat to civilized society. In “Fabricated City”, Park suggests that rather than online gaming destroying young people's mental health, it enables young people to form their own communities, which are productive of good mental health rather than destructive. In the film, adults are dangerous and destructive and the ones who manipulate young people to conform to societies' a-priori assumptions about youth culture. Kwon's status as gamer is almost enough in itself to convict him, as, after all, gaming causes deviant behaviour?

“Fabricated City” is extremely fast-paced, from the opening action scenes which take place inside the virtual world of the gamer, to the increasingly frenetic chase scenes as the police attempt to track down Kwon and his motley crew of gamers, as they race against time to prove Kwon's innocence. While structurally it fits within the Korean revenge genre, it turns the conventions of the category on its head. Usually, the revenge consists of the hunter and the hunted and constructs the two as doubles or mirror images of each other. Here the emphasis is on group identities and the difference between youths and adults. The online community here is portrayed in a positive light, while the offline community made up of representatives of the state: prison officers, policemen and lawyers are almost wholly negative. In “Welcome to Dongmakgol”, Park suggests that the conflict between North and South Korea could be overcome by cooperation and understanding, a similar thing is true in of the conflict between adult and real society and youth and online society in “Fabricated City”.

Ji Chang-wook is well cast and his hero's journey is believable as is his transformation from naivety to self-knowledge. However it is Shim Eun-kyung as Yeo-wool, a shy hacker who, when we first meet her, can only communicate with others through her mobile – thus embodying fears around shutins and loners in South Korea – who is a revelation, and the film is as much about her journey to self-determination as it is about Kwon's. Oh Jung-se's performance as the corrupt lawyer Min Chun-sang is slightly frantic and could have done with being tempered in at times. However, it is obvious that Oh had a great deal of fun making “Fabricated City”.

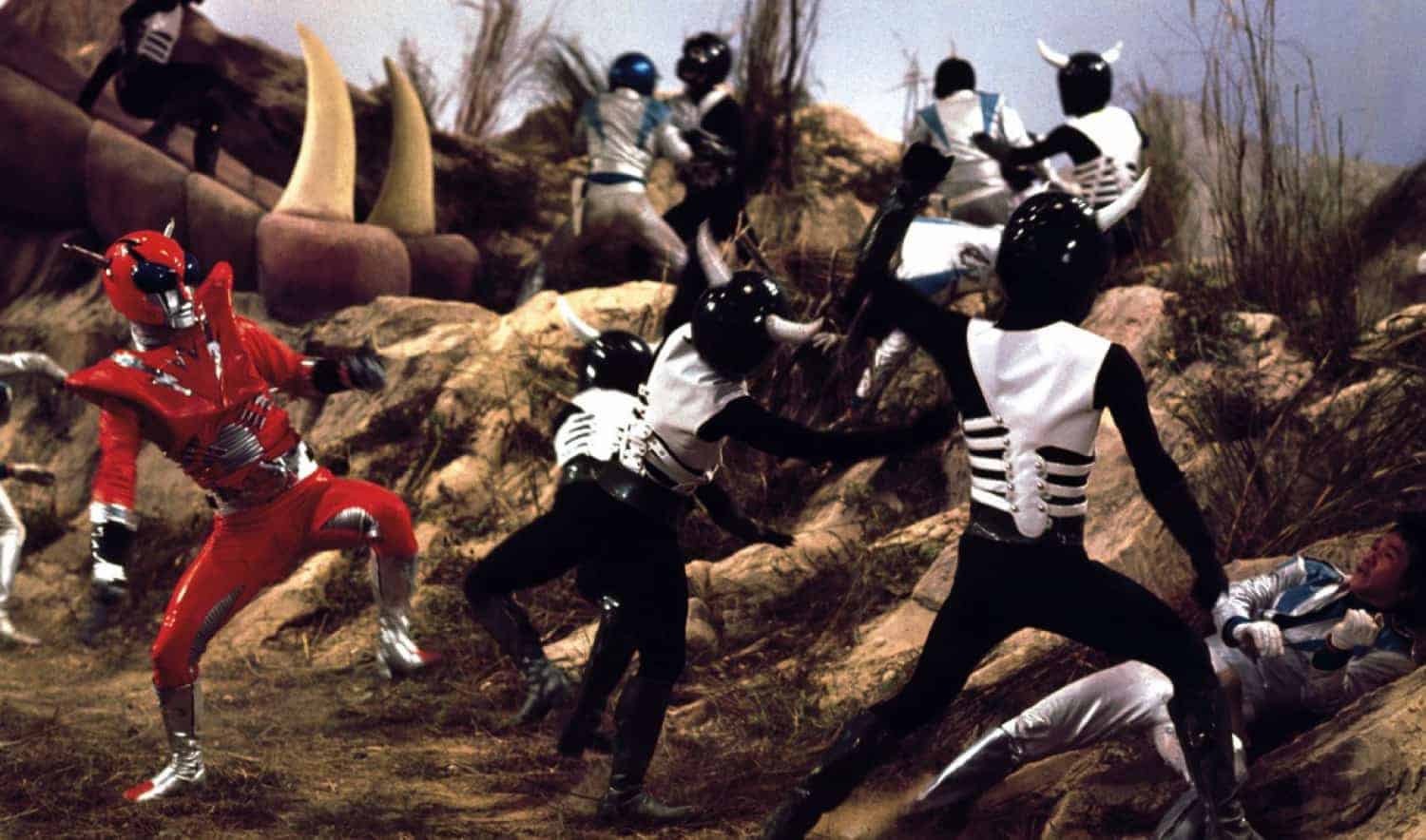

Overall, the film is visually stunning, the intricately choreographed action-sequences mimicking the frenetic pace of the narrative, and with extremely inventive car chases. The cinematography mirrors the multiple levels on which the fabricated city of the title exists, and the almost seamless shifting between virtuality and reality.

Like many South Korean films, “Fabricated City” doesn't sit easily within genre categories, but that is in fact its charm. It is difficult to classify the film, but it isn't difficult to recommend the film. I only hope that Park doesn't leave it another 11 years before his next one. He is a director whose films deserve to be seen and appreciated by a wide audience. Without doubt, Park is a director to watch out for.