The interview was initially conducted on April 2017

Konrad Aderer lives and works in his native New York City as a field producer, videojournalist, and editor for NGOs, local TV, and nonprofits, including the UN and the ACLU. Since he established Life or Liberty (lifeorliberty.org), a nonprofit multimedia project, in 2002, much of his work has focused on immigrant communities coping with deportation and detention. He is also an actor and director, known for Resistance at Tule Lake (2017), Enemy Alien (2009) and Rising Up: The Alams (2005).

We speak to him about human rights, cinema, his career, the events at Tule Lake, and many other topics

You have been involved in immigrants' rights issues for quite some time. Why is that, and can you tell us a bit about lifeorliberty.org?

If you go to lifeorliberty.org, you'll see I got involved with the fight to free a Palestinian detainee named Farouk Abdel-Muhti. I produced a short to create awareness and involvement and a campaign to get him out, and eventually the story became my first feature documentary, “Enemy Alien.”

I made a film about Shokriea Yaghi, whose husband was one of the first post-9/11 detainees. She was trying to get him back in the country after he had been detained, starved, and deported to Jordan without warning and that became “Life or Liberty.” And that also became the title of my overall project. I saw that the government was handing us a false choice of choosing between our life or security and our civil liberties. Instead of life, liberty or the pursuit of happiness, they told us we could have life or liberty, but not both.

And “Rising Up the Alams” is about a Bangladeshi family fighting the deportation of the father following special registration post-9/11. My goal was not only to focus on resistance instead of victimization but —how people more vulnerable than American citizens still resist against these policies of surveillance, arrest, and detention.

Do you think that cinema is obliged to deal with social and political issues, and how much impact do you think a film can have? Is the documentary, as a medium, the best way to highlight these issues?

Telling a dramatic story through real-life experiences is a very powerful way to engage people in an issue, rather than reading fragmented pieces of social media or articles. To sit and have a story unfold is still an effective way to galvanize people. The main point is to tell human stories but also to give people a sense of cause and effect in people's lives and what the impact is. That, to me, is how to get inside people's skin when they're faced with dire circumstances. When everything they've worked to build for decades and it's taken away and when they don't know if they're allowed to stay in the US or not, it's important to understand the choices people make as they're going through that.

You also work as editor, producer and cinematographer in TV and films. Can you tell us a bit about these capacities and how has your experience in other people's productions helped you with your films?

I didn't go to film school. I had some really good mentors and friends who had professional skills that helped me until I was able to be self-sufficient as a filmmaker. I learned a lot watching other filmmakers but mostly through doing my first feature, “Enemy Alien” where I started off not having any skills and ended up shooting, editing and writing it.

How did you decide to deal with the the Tule Lake camp and how did “Resistance at Tule Lake” came about? Is the main purpose of the documentary to raise awareness for these dark episodes in US history?

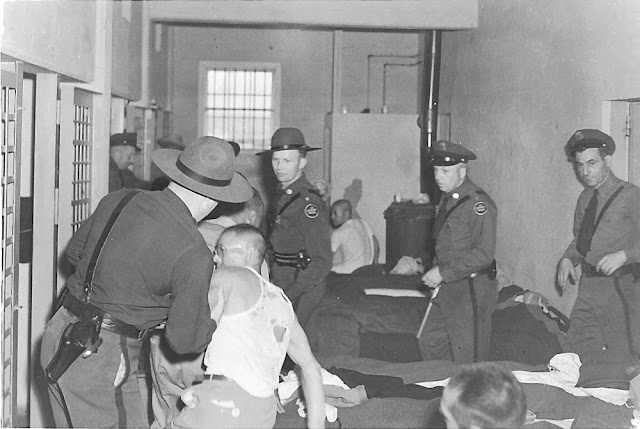

When I was making my first film “Enemy Alien” about Palestinian activist Farouk, I was looking for a parallel in Japanese-American history. I found it in Tule Lake. Pretty much everything that he did: conduct hunger strikes, reason with his captors, fight illegal cases on base of constitutional principles—that's all the things that Japanese Americans did at Tule Lake. And they had the same kind of consequences—beating, torture, deportation, yet they still persisted, which is why I felt this story was invaluable to tell because it was so little-known.

The documentary implements a somewhat old fashioned style, with the narration and the subsequent zoom-ins and zoom-outs of the various photographs appearing on screen. Why did you choose this style?

I wanted to immerse people in the visual experience of Tule Lake. As I worked with my amazing associate producer Natalie Samuel, we discovered a great volume of visual materials for the Tule Lake segregation center. I feel that immersing yourself in stills is a great way to contemplate the terrible beauty of a place that was built to incarcerate people in a natural setting, bounded by two very striking mountains that become like characters in the film. Stills are what have survived to show glimpses of the torture and mistreatment people experienced. Since sifting through an archive is not the same as experiencing a story, I wanted to immerse the viewer in the visual experience of this place, and the glimpses of state violence people were subjected to. It takes time to absorb an image and I wanted to give the viewer a chance to, while hearing first-hand experiences of the people who lived through this.

One of the people speaking in the film states that, after the bombing of Pearl Harbor, the Japanese living in the US West Coast fell victims to propaganda, hysteria, and ignorance, with the government and the majority of citizens considering them potential enemies of the state. Do you find any justification for this attitude, considering what has happened in Pearl Harbor?. Of course I mean in terms of mentality not of the horrendous treatment Japanese Americans received.

The fear and hysteria following Pearl Harbor and 9/11 is a very understandable human reaction. But it's in times like this for which our constitution is written, to protect against overreactions and betrayals against fundamental principles of human rights. We don't need the Bill of Rights when everyone feels safe; we need them when people are inclined to feel threatened by an “other” or by a perceived enemy with a foreign face living in our midst. In my films, I try to give people a rational understanding of how the government betrays its ideals to satisfy this human reaction, and an emotional understanding of the price people pay when they become the targets of wartime hysteria.

Particularly during the last decade, the accusations against the Japanese for their acts in WWII have been very intense, especially regarding the concept of the “comfort women” and their general treatment of the people they have conquered. Do you find that justified?

There's no denying the Japanese government committed atrocities during WWII. However, the Japanese Americans did not play a role in that. So that's a separate issue from the mass incarceration, mistreatment, torture, and deportation of Japanese-American citizens and aliens during WWII.

What kind of films do you like to watch and can you name some of your favorite documentaries?

I take a lot of inspiration from narrative films as well as documentary films for my project. I like films that show how a powerful moral principle plays out through characters like Martin Scorsese's remake of “Cape Fear.” “The Fog of War” by Errol Morris, gave me a lot of inspiration as far as style and the use of archival footage. I see my film as following in the footsteps of other documentaries on wartime incarceration like “Rabbit in the Moon” by Emiko Omori and “From a Silk Cocoon” by Satsuki Ina. I also got to know Linda Hattendorf while she was finishing her great documentary “The Cats of Mirikitani,” which also touches on Tule Lake and learned a great deal from her.

What are your plans for the future?

I want to keep showing my film in Asian American communities but also engage Muslim, Arab and South Asian communities with screenings and call attention to what is happening now. We'll be having a public television broadcast presented by the Center for Asian American Media Spring 2018. Once I'm done putting good educational distribution in place for this film, I hope to flesh out my next project.