The 1960s French champagne socialists would appreciate Lee Soojung's documentary about a middle-aged former factory worker Jaechun, who discovers art as a form of protest, joining the group of people with the same aim to fight their way back to the employment through activism. Although he neither speaks in math or pretends to have become cultured over night, Jaechun does find himself in this new milieu slowly overcoming his problem with being introverted and shy. This is the information given through the opening title cards that serve as a form of silent over-voice that continue to guide us through the film. Speaking of which, this isn't the only thing that mimics some of the silent movie elements. The title cards, with white letters on the black background are accompanied by intense piano solos.

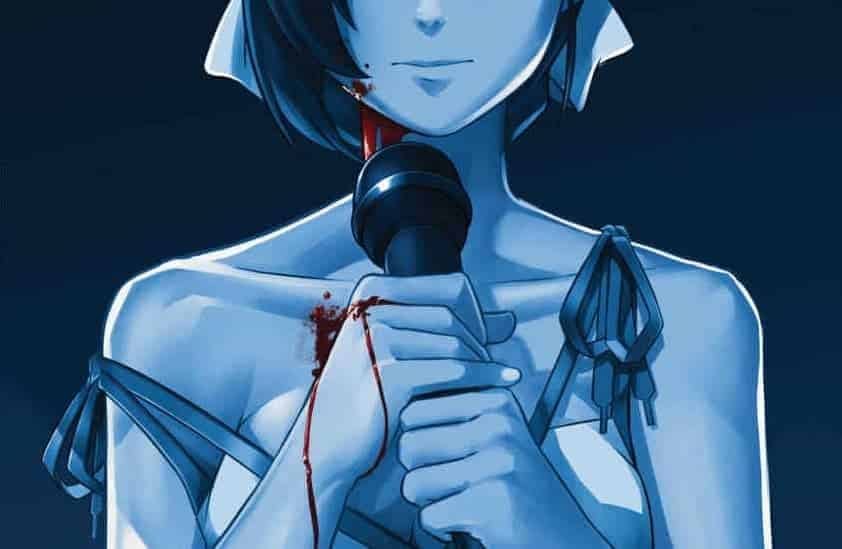

“Sister J” is screening as part of Women Direct. Korean Indies! – Korean Women Independent Film Series at the Hong Kong Arts Centre

Not losing focus on the problem of growing unemployment through the so-called ‘re-structuring', Lee observes the all-workers theatre troupe performing Shakespeare's plays on stage, bringing the blue collar milieu close to the classics that speak of injustices in a language that feels both close and distant to men robbed of their basic rights. It's as much a liberating process as a challenge for workers whose lives where consumed by heavy labor that kept them away from the world of theatre or ‘classics' in written word. Surrounded by bourgeois leftists, they suddenly find themselves in a culture-fuelled environment which offers them philosophy, poetry and music as pillars of support. We even get to see activists reading out loud from heavy weight philosophical works such as Nietzsche's ‘Thus Spoke Zarathustra', in the modest improvised street shelter that protects them from the bitter cold.

One could debate the truthfulness of the slogan “No guitar, no music” on the men's T-shirts that is supposed to summarize the movement's goals, but only after finding out that they all worked for a guitar manufacturer, the viewer embraces this subjective truth. The men even have a band which performs songs about their own experiences, such as sacrificing private life for the benefit of the company, risking health, letting go of personal happiness and never questioning inhuman demands coming from the management. Another music coming from different protesters blends in, and the streets become alive with the sound of rock'n'roll bends who join the protests.

Based on a compilation of stories collected from workers' milieu, this straight-as-an-arrow account of the aftermath of factories' reforms that claim many jobs, focuses on one man, laid off after thirty years of work. Seven years after being fired, he is still protesting with the others, calmly and without illusions about the outcome of their efforts to reverse the injustice. One court appeal after the other are being dismissed, claiming (among others) that the mass layoff due to a management crisis was completely legal.

Lee Soojung's “Sister J” is as much an observational documentary about unconvential means of fighting for workers' rights, as about the soothing power of culture on people.

First 90 minutes are shot in black & white, and the new ‘colourful', final, shortest chapter of the film starts when the documentary moves to Jaechun's hometown Daejon, where the former guitar craftsman returned to, now working as a construction worker. In a sense, when colour penetrates the screen, the joy of life ebbs away. It's back to naked work all over again, without music, poetry and intellectual exchange with those who Jaechun had more to share with than labour.

If there is something missing in the process, than it's understanding who Jaechun is, including the gender bending title of the movie. Additionally, it would be interesting to understand the very structure of the protests and to be given any hint at who people behind certain cultural events are. At the same time, one is immersed into this world of workers' cultural revolution (not related to something that was called that, but implied all kinds of repercussions that made it the opposite of its name). “Sister J” is a film that stays in one's head.