“Hoop Dreams” (1994) broke the mould for high school basketball documentaries, charting the progress of young hopefuls as they balance education, social pressures and a dedication to sport in the face of local celebrity. And while Erica Tanamachi's “Home Court” covers a similar scenario, its journey is a very different one through high school basketball.

Home Court is screening at CAAMFest

Teenage basketball star Ashley Chea, a Californian of Cambodian descent, has one ambition: to play basketball professionally. And the starting point for this is high school basketball. She enrolls at a private school with a strong basketball heritage, where her coaches are more like family than her parents. And therein lies the problem: with Ashley's parents working hard to support her, combined with her mother's lack of understanding basketball and middle-class American customs, she gradually becomes more and more distant from her family as college looms closer. But she still needs to get there first, and has to battle injury, anxiety, education and the opposition to gain a much-coveted college scholarship.

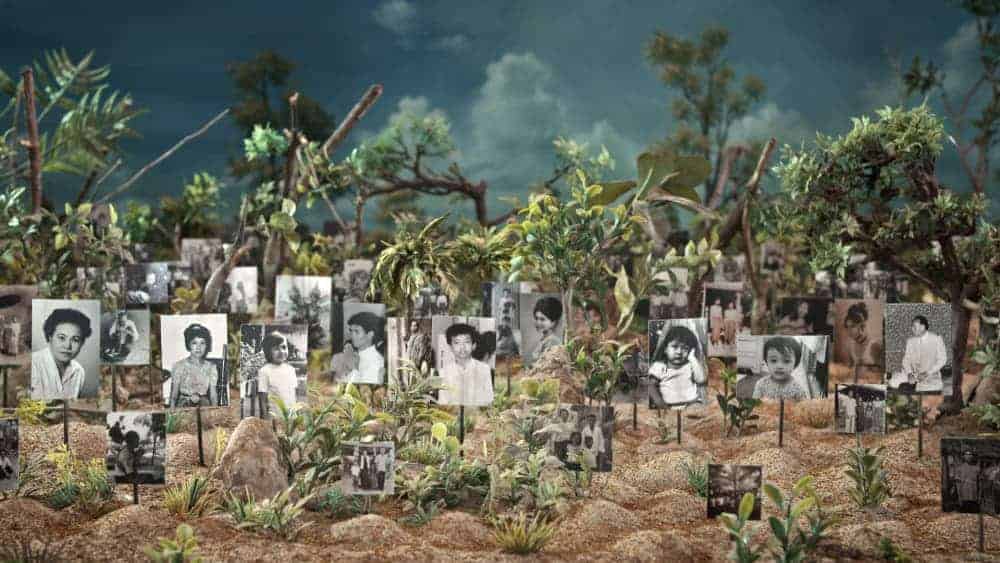

In many ways, Tanamachi portrays Chea as a typical teenager, unable to control her emotions and at odds with her parents. But as a daughter of Cambodian immigrants working at a garage and doughnut shop, she doesn't have the same home life as her classmates. And this is the main crux of the documentary, with the generational differences between migrants and their children born to a different world.

Her parents work hard so she can go to a good college and get a good job. As such, they may have to stoically neglect their children's wants and needs. Tanamachi juxtaposes her parents long working hours with basketball games and Christmas gatherings they yet again fail to attend. While Ashley just wants to play basketball and hangout with her friends.

Outside of her family, she also has to battle against stereotypes of Asian-Americans playing basketball. Not taken seriously, she has played for all-Asian teams who had to show their skills to silence the mocking. Here, a potted history of Asian, notably Japanese, basketball teams is provided since the Second World War. She has a closer relationship to her Japanese-American coaches than her parents, since they are more understanding of her world. Despite her dad introducing her to basketball, when deciding which college to attend, she wants to tell her coach more than him; her parents coming from a culture of minimal expression which she doesn't understand.

The commodification of the American school and college system is portrayed throughout, whether intentionally or not. College open days are photo shoots in the basketball uniforms, showing the great arenas you will play in. This is as close to professional sports as you can get. Very little about education is discussed – it's all about the basketball team, with coaches admitting players in certain positions graduating will influence which new students they want at their school.

The final third of the documentary is a somewhat relentless chronology of her high school team's charge through the regional championships until reaching the state tournament, with suitably emotive music. Far from an impossible dream, here basketball feels a logical career progression from school to college. The injuries and Asian heritage mentioned as possible barriers don't seem present, which shows a sign of progression in society.

When leaving for college, both Ashley and her mother express a sense of regret at not communicating enough and taking interest in each other's lives. But she has two homes and two families. Her parents provide the foundation from their hardworking endeavours; while her coaches guide her to a better life. While she often feels trapped between various worlds, she is a young woman who receives a lot of love and support to allow her to flourish.