by Epoy Deyto

Brillante Mendoza, Best Director laureate from the Cannes Film Festival, dropped his latest film, “Pula,” quietly on Netflix earlier this month. The film marks one of the two reunion projects between Mendoza and actor Coco Martin years after their last collaboration in “Kinatay” (2009). This small-town crime thriller seems to bridge more than just the two figures.

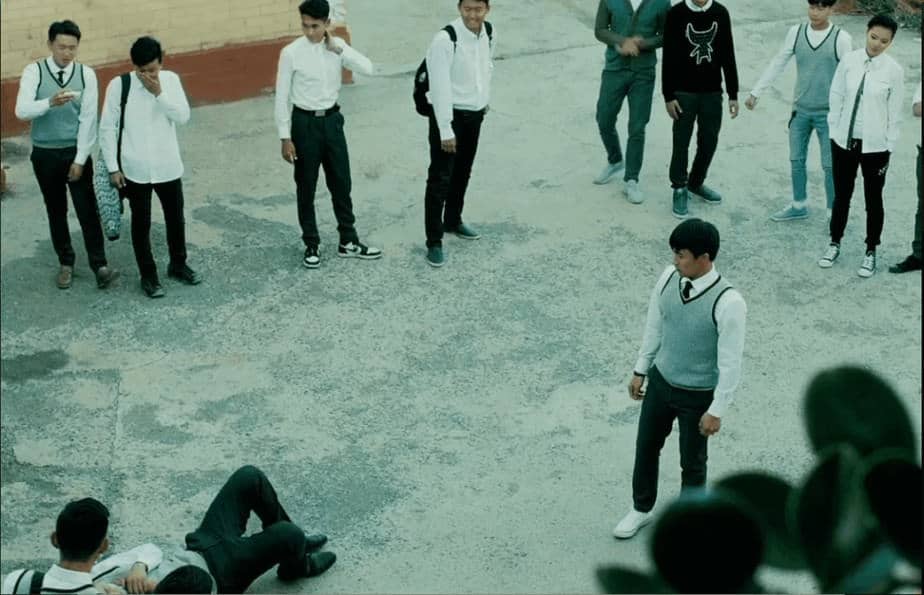

The film navigates a fictionalized version of the small town of Pola depicted as a devout catholic fishing community where citizens live far from the town center and from each other. The title of the film is a wordplay of several layers. The first layer is the word “pula” being the literal translation of the color “red” associated with the red tide plaguing the town’s fishing industry at the brink of a typhoon. From this setup, we are introduced to Daniel (Coco Martin), a police officer under the command of Captain Raymond Anacta (Reymart Santiago). Within this calamity, the police are tasked to help with the distribution of the relief goods which adds to the irregularity of Daniel’s presence at home to tend to his children and his pregnant wife, Magda (Julia Montes). Magda’s pregnancy made Daniel happy, but also so sexually frustrated that he brushes it off by going on motorcycle rides. Behind Daniel’s back, Raymond and Magda are having an affair and they are trying to figure out who is the baby’s father.

The town of Pola is not without its contradictions. Its catholicism is seen with a hint of belief in the supernatural and faith healing which setup makes the coming of the typhoon seem ominous. This is where the second layer of wordplay is found: “Pula” is just an altered version of the town’s name, “Pola”, a variable of the Spanish word “polir” which means to cleanse. This omen brings us to Tricia (Christine Bermas) who is stopped in her feet by the darkened sky, canceling her plans to elope with his boyfriend, Jeff (Vince Rillon), at the last minute. This faithful town is rattled one day by the discovery of Tricia’s murdered body who is reported missing after she fails to return home.

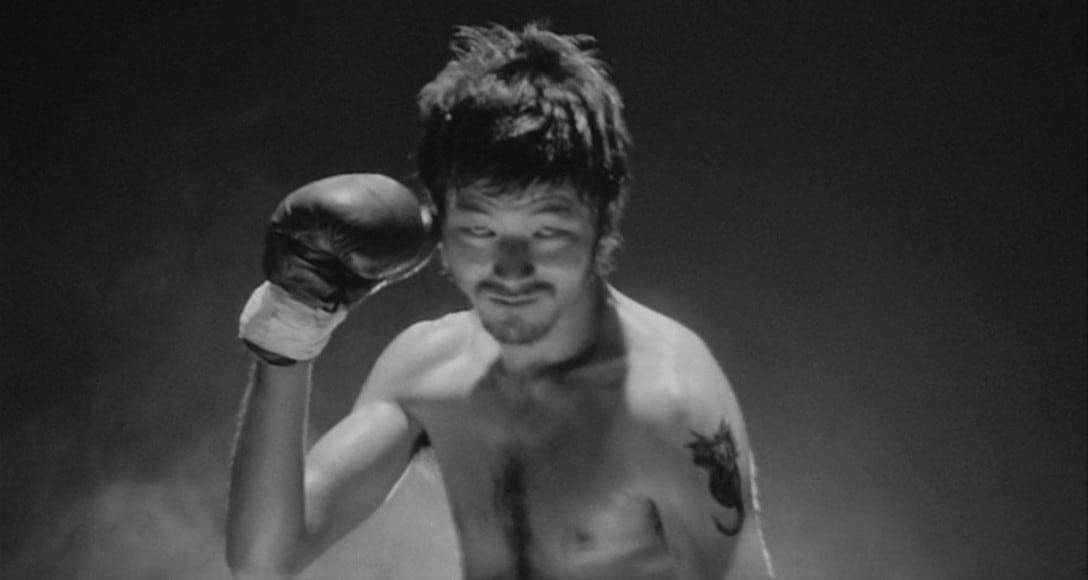

While the camera work done by Jao Daniel Elamparo follows the staple documentary-like style of Brillante Mendoza, other aspects of the visuals seem to work differently. The first technical thing that one can notice about Pula is its washed-out, sepia-toned color grading. The color effectively highlights the reds in the film as though following through the layers of pula. This treatment contrasts the sense of realism that the camera-work provides and the film exploits this stylistic tension to paint the supernatural creeping slowly within the whole narrative.

If you like Pula, check also the interview with the director

This stylistic tension also affects the progression of the performances in the film. We may recall Martin being a constant collaborator on Mendoza’s earlier films where he almost always performs at a quiet tone. In “Kinatay”, for example, the situation his character Peping was in forces his reactions to be lowkey even though the violence around him progresses distastefully. Martin’s performance as Daniel in Pula starts the same: as part of the town, to the point that it makes him disappear. However, the tension in Martin’s performance arises as his cycle of appearance and disappearance changes him from timid to controlling.

Martin’s subtly changing performance progresses as the typhoon brings more chaos to the town. A series of misfortunes hit Pola as days go by. There is no way these are coincidental. From the color, the ominous situation, the quiet town, down to the performances, “Pula” brings the combination of its elements close to an apocalyptic narrative.

It is quite common within Filipino films to associate the typhoon with the apocalypse. In contemporary films, Yam Laranas’ “Patient X” (2009) and Dodo Dayao’s “Violator” (2014) made use of the same trope. The presence of police authorities as part of the main characters made Pula closer to Dayao’s “Violator. In Dayao’s apocalypse, the devil manifests in the body of a homeless kid who is brought to jail because of the trouble he caused that same rainy night. But what made Mendoza’s “Pula” set itself apart is how the source of the ultimate evil in its apocalypse does not come from an outsider but within the very village itself.

Mendoza’s apocalypse poses a political question: what if the otherworldly evil resides within the figures of power themselves? Martin’s involvement in Pula as its main character perhaps makes the movie close the circle that “Kinatay” opened years ago by asking the same question. Like “Kinatay”, Mendoza slowly unfolds his interrogation of this question in ways that make “Pula” somewhat uneven in pacing that drags at first and then rushes later. This pacing makes sense, however, if we go back to its attempt to bridge the supernatural and the political. This might be how the apocalypse would feel.

This imbalance in treatment, however, may be jarring to some. The rush in the last third, especially how Mendoza approaches its conclusion, may be upsetting. But these are all by design. And if you’ve been following Mendoza for a while, you know that he does not just design the direction of the storytelling, but also the film set as an extension of his years of practice as a production designer. “Pula”, in one way or another, is an auteurist gesture that makes the film a sample of what can come from absolute artistic control.