By Earl Jackson

For a long time, Japanese cinema of the 1980s was a closed book to me. I just could not engage with the soft-focus, candy-pastel dreamscapes, the ubiquitous permed hair for both sexes, the relentless innocence of the idols who seemed to have learned acting from hostage ransom videos, and the ramshackle macho veneer concocted with crayons and a bullhorn. But in 2004 I attended an immense and beautifully curated 1980s retrospective sponsored by the Japan Foundation held in an upscale shopping mall in Seoul. That intense exposure was a real education which included an introduction to the almost preternatural, haunting countercharm of Yusaku Matsuda, amplified by the devoted Korean Matsuda fans I met there.

In recent years, international attention to the work of Shinji Somai and Nobuhiko Obayashi has filled in vital pieces of the 1980s, however Matsuda's cult status in Japan has yet to spread beyond domestic screens. Of course, Matsuda did not possess the martial arts pyrotechnics of Sonny Chiba, the gravitas of Bunta Sugawara, or the tremulous vulnerability of Ken Takakura. But what his predecessors had that he lacked most was time, dying of cancer at 39. Long before his diagnosis, however, Matsuda was painfully aware of having already run out of time. He often referred to himself as having “come too late” [遅れてきた]. Looking at the 100 films Takakura had made, he wondered, “Can I make that many films? Is there time for that?”

And it is not just that he did not live long enough, rather he was born too late. The yakuza genre was in decline and the stars of that period were in their final years. But ironically, this predicament is part of his mystique; he is the man that fell between times if not fell out of time – he emerges in films wildly out of context, defying categorization.

In “The Beast to Die” (Toru Murakawa 1980), Matsuda's character is an enigma for most of the film – a classical music devotee who kills a detective for his gun and launches a reign of terror. But even his name is not divulged until half-way through the film and the past trauma that deranged him is withheld until the climax (Figure 1).

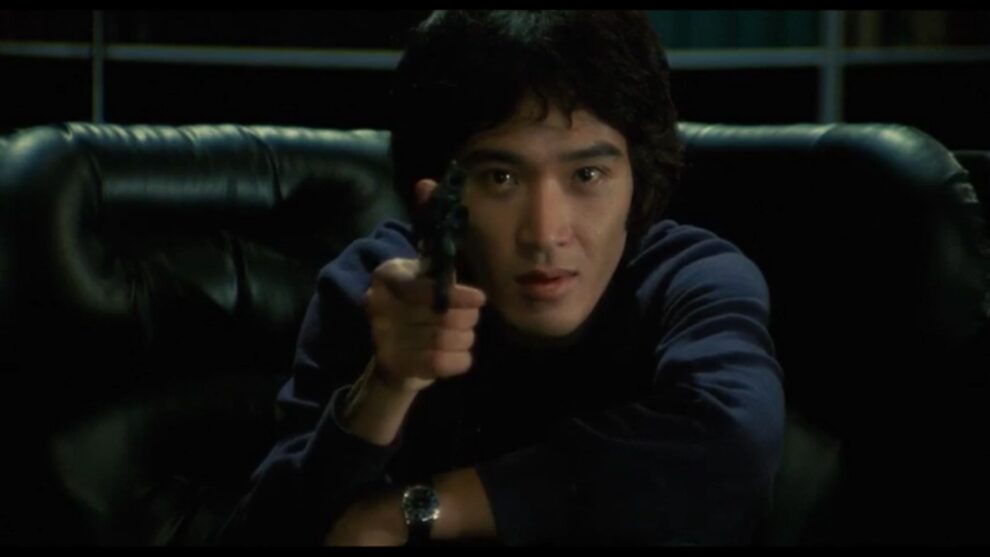

In 1986 Matsuda himself directed “A Homansu”, in which he starred as a man suffering from amnesia who becomes fiercely loyal to a gangster-in-trouble played by Ryo Ishibashi. Without a name, the amnesiac is at times called kaze 風– “wind” or fu – a homonym for 不“not”, accommodations to an identity whose mystery only deepens in the climax (Fig. 2).

The number of times he plays a man with no backstory or a backstory that emerges obliquely and nearly after the fact contributes to his composite on-screen personae but also resonates with his off-screen life. I will read Matsuda on those parallel tracks: first through his ex wife's memoir and then through the “Game Trilogy” (Toru Murakawa 1978-1979). My reading of the trilogy will also focus on two tracks: the character Narumi's negotiation with the game, and the relation of Matsuda's image to each film's particular mechanics.

Michiko Kumagai first met Matsuda in a theater group in which they were both studying acting. They were married from 1975 to 1981, although they lived together for several years before that. When they first moved in together, Matsuda would occasionally question Michiko's commitment to him, seemingly out of the blue. One windy night he took her out on the roof where he sat outside the protective fence and told her to sit beside him. She was frightened and hesitant but he insisted. Looking down, she trembled and felt like crying.

“Why are you acting like this? You're testing me.”

“It's ok. Now I understand fully. You don't trust me after all. If you found out the truth about me you would run away. You would definitely run away.”

(Michiko Matsuda 越境者 松田優作 35-36).

Matsuda is an accomplished novelist, known for The Perfect Education 完全なる飼育 series of bondage and discipline fantasies that have been adapted into films. She uses her stylistic gift in depicting Yusaku's abandoned attempt to confess a secret as a gothic romance – first by continually describing him as tall, handsome and seductive, yet with darkening moods. Like a Heathcliff he was on the precipice of telling Michiko his dangerous secret on a real precipice (the edge of the roof), putting her in actual danger. Ironically, Matsuda would take on the Heathcliff role in Kiju Yoshida's 1988 adaptation of “Wuthering Heights”, one year before the actor's death.

Michiko did not learn Yusaku's secret until several months later, when her uncle visited her with the results of the investigation her family had commissioned: Yusaku was an illegitimate child; his main residence had been some kind of bordello that had been the target of police action, and his nationality was Korean (Matsuda 越境者 38). Her uncle warned her that Yusaku was an unsuitable partner and implored her to “consider her future”. She agreed to think about it but silently refused to even consider separating from Yusaku.

Check also this interview with the author

“Now I understood why Yusaku was compelled to test the extent of my commitment to him. He was suffering in the clash between wanting to tell me about his identity as a zainichi Korean and his fear that it wasn't the right time.

“I decided not to say anything to Yusaku about what my uncle told me. I would pretend not to know anything unless he feels like talking about it. People do not choose what environment or circumstances they are born into. Imagining how much prejudice he had been exposed to as a child, and the humiliations he endured, my heart was filled with love for him.” (越境者 39).

Certainly this is a moving story, and Michiko's reaction to the news is both admirable and remarkable for the time. But the sociohistorical circumstances need to be recognized. In her memoir, Yusaku's story becomes her story. Even when he appears in this narrative, it is only to fail to tell his own story. His suffering or any other experience he had as child is simply Michiko's conjecture, not Yusaku's testimony. Michiko's scenario reads like a tv-drama – except that in 1971 when it happened, no such drama could have been even conceived of, much less produced. And even if such a drama could be produced in 2009 when she wrote the memoir, there would be retroactive repercussions against the Yusaku legend, the national memory of the star before the revelation. Now I can explain why I opened this essay with the film festival in Seoul. The Korean Matsuda fans I met eagerly told me how Matsuda had secretly claimed Korean citizenship at the height of his fame. They were so insistent on this story, I never challenged it or investigated it myself, and over time belief in it was a habit as part of life in cinephile Korea. Now I realize that the fantasy of Matsuda's claiming Korean citizenship was an extension of that fanbase's admiration of and identification with Matsuda. Thus the figure of Matsuda takes on radically divergent claims.

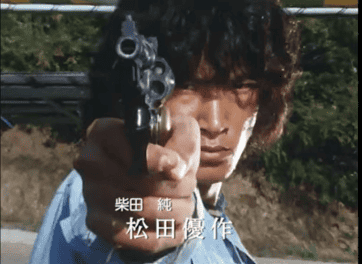

Yusaku's secret becomes an urgent problem to solve two years later, when he is signed on as a regular in the wildly popular crime television series, 太陽に吠えろ “Taiyo ni Hoero” [Howl at the Sun]. His first appearance as “Detective J-pan” was well received and he began to get fan letters. But he became worried and told Michiko that now he had to become a naturalized Japanese citizen. Although Michiko does not mention it in her memoir, there was added pressure since the star of the series, Yujiro Ishihara was the younger brother of the LDP diet member, Shintaro Ishihara, a rabid Japanese nationalist and xenophobe. Yusaku asked Michiko's help. Michiko's father was also a politician in the LDP and had connections with powerful people who owed him a favor. Michiko wrote her parents a letter and turned the tables on them. Originally her uncle had asked her to consider her future if she stayed with Yusaku. Now she asked her parents to consider the fate of their future grandchildren if they did not help (越境者99-100).

That argument worked, and her father began the process of naturalization. Michiko includes part of the petition that Yusaku had to write personally:

“Since July of this year I have been appearing as a regular in the very popular Nihon Terebi series “Taiyo ni Hoero”. The program is enjoyed by families and the viewership is broad – from children to adults. Many viewers have kindly expressed their encouragement to me. At present I use the name ‘Yusaku Matsuda' and even my colleagues on the show do not know [my birth name Yusaku Kim]. If they learned I am a resident Korean, everyone would be disillusioned. This would especially betray the dreams of the children watching.” (越境者103).

Yusaku Matsuda was granted Japanese citizenship in late 1973. But even this victory had to remain secret, as any announcement of it would have defeated its purpose. Matsuda was thus secretly declared to be who he already was. And he won this right, not by appealing to justice but rather by appealing to Japanese racism. This secured his role in “Taiyo ni Hoero”, and also prepared him later for the cruel games of Murakawa's trilogy.

Thanks very much for the first in your series about Yusaku Matsuda. He was a uniquely charismatic actor and I’ve enjoyed viewing and frequently re-viewing his movies. Yes, he died too soon! I appreciate knowing more about his personal life and the circumstances that made him such an interesting actor.

thank you very much – I appreciate the feedback.