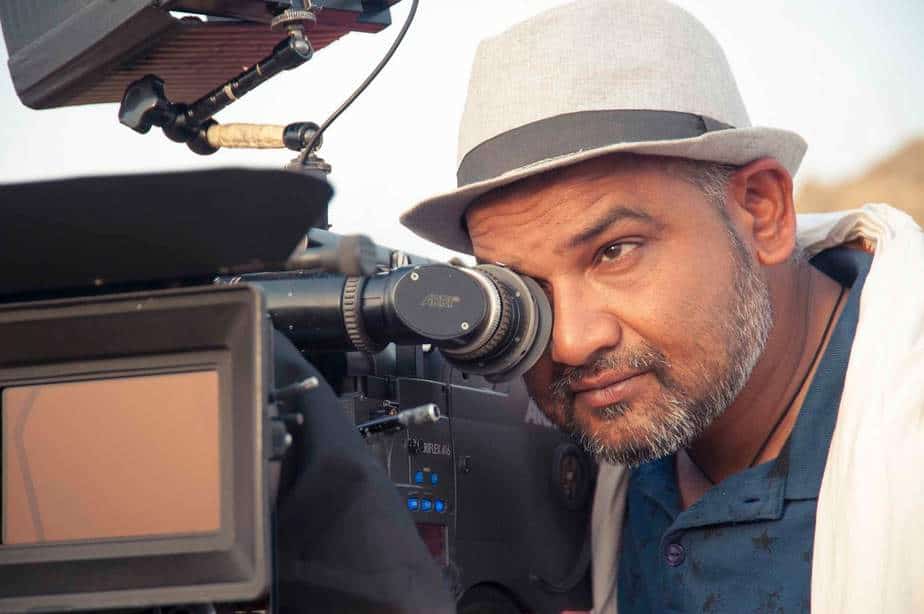

Toda is an independent documentary filmmaker based in London and Osaka whose work focuses on marginalized communities. Her films have screened on BBC Storyville, NHK, and The Guardian and at major international film festivals like Hot Docs and Melbourne International Film Festival. Toda returned to Japan for the first time in over 22 years to make “Of Love & Law“, which is the first ever documentary to win Tokyo International Film Festival's Japanese Splash competition.

On the occasion of Of Love and Law screening at Japan Cuts 2018, we speak with her about the inspiration behind the film, “reading the air”, Japanese conservatism, the reception the film enjoyed in Japan and the ongoing cases the film deals with

*Questions provided by Rouven Linnarz

What was your purpose in making “Of Love and Law”?

The film is about the challenges of being yourself in the face of cultural and legal setbacks. It questions what we accept as the norm, and invites the audience to look at our own role in challenging or sustaining those norms that do not serve everyone equally.

There is this phrase of “reading the air,” which seems to one of the underlying themes of the film. What is the meaning of this phrase and why does it create social pressure?

It means that you are forced to understand what is expected of you, that you are not supposed to disagree with their opinion, because by offering an alternative opinion it might create a very awkward situation for everybody. So you are not supposed to really be opinionated, you are not supposed to go against the mainstream way of thinking, because if you do, you are kind of considered of being selfish or disruptive.

In the film they say it twice, one by Rokudenashiko , who explains that people who can read the air are considered proper adults and those who cannot are the ones who cannot understand what is expected of you and are the ones who should be “shut away”. Rokudenashiko was always opinionated and what she does with her art is all about revealing unspoken rules and unspoken underdictions in Japan.

The second one is a teacher who did not stand up for the national anthem during the graduation of the public high school she was working, and she talks about how times have changed; whereas before there were many teachers who did not want to stand for the national anthem, due to the symbolic relation with the Japanese Imperialism. However, because of the way society has turned, it is a hard opinion not to want to stand up during the national anthem, you become a minority if you don't. And she says that everyone is breathing the air and stand up during the national anthem because that is what is expected of people now, it is kind of compulsory if you are attached to public service.

In your opinion, would you say that the Japanese, as a majority, are conformists and conservative?

Yes and no. I think we are becoming more and more conservative, but also when there is a movement towards the right, there is an underground movement that counters it. So overall, because of the politics we have right now, it seems to me that it is becoming more conservative, but in the same tim,e there are individuals like the lawyers and the clients in the film who are fighting it and I think that there are more and more people like that. So there is always a counter movement to the mainstream movement.

Was “Of Love & Law” screened in Japan? If yes, which reactions did you encounter?

We premiered in Tokyo international October 2017. The response of the audience was good, we had two screenings and both of them were sold out, and we won an award in our category, so it was really well received.

Some of the cases of the two are still ongoing as the film ends. Do you have any updates on those, and do you still follow Kazu and Fumi?

I am not filming them, but I do follow them. Rokudenashiko is still awaiting for the verdict, so there is not much news there. The teacher is still fighting against the city of Osaka and she is also following other cases in Tokyo where their petitions have repeatedly been turned down. So there is not much change there either. Regarding the case against the university, the one where the family was presenting the case about the student who committed suicide as a result of being outed by a classmate, the family of the deceased and the accused were able to reconcile outside the court, but the family is still asking for responsibility from the university but they refuse, so that's ongoing.