“I like the feeling that the sea isn't judging me. […]”

“Strange. It's judging me all the time.”

For many directors, or artists in general, one of the possible developments in one's career might be the path towards expansion. The lure of big budgets comes with great responsibility, but also with the opportunity to realize concepts on a much bigger scale economically than before, as well as reaching a bigger audience. If one takes for example the careers of artists like Christopher Nolan or Darren Aronofsky, the opportunity leads to a realization of one's vision with vastly different possibilities while not eliminating the element of failure, a condition which in the big budget-world will not be tolerated for long.

Other artists like Thai director Pen-Ek Ratanaruang consider that the key to move forward is reduction and limitation. Whereas his films so far have been financed with a relatively small budget, the filmmaker has found his style within the use of small spaces and narrow corridors, if films like “Ploy”, “Last Life in the Universe” or “Invisible Waves” are any indicators. In an interview conducted by cinemasie, Ratanaruang explains how his lack of a formal education in film has made him increasingly aware of how telling the story visually developed into a learning curve for him, with each of his films constituting an important step within that process. In contrast to other representatives of what is defined as Thailand's “new wave” such as Apichatpong Weerasethakul, Ratanaruang is quite outspoken about him not having a thought-through plan in his head when the filming begins, but sometimes following his instincts as well as the spacial and economic limitation, he has to face in order to finish the project. Imagining spaces, whether its tight corners, staircases or even toilets have thus become one of the trademarks of his cinema.

Buy This Title

For “Invisible Waves” the director teamed up again with Japanese actor Tadanobu Asano, who had already played the male protagonist in “Last Life in the Universe”, a movie Ratanaruang, according to his own words in the interview included in the British DVD release, wanted to improve upon with his new project. Therefore “Invisible Waves” uses the theme of guilt, a feeling which, for Ratanaruang, is perhaps inevitable for him and everyone else, which comes “with the job” as director as he has to reject people's ideas or hurt people's feelings in order to fulfill the demands of the production.

“Invisible Waves” follows the principle of a Kafkaesque parable of the inevitability of guilt for everyone, the pressure it has on our lives and how it slowly closes in on us.

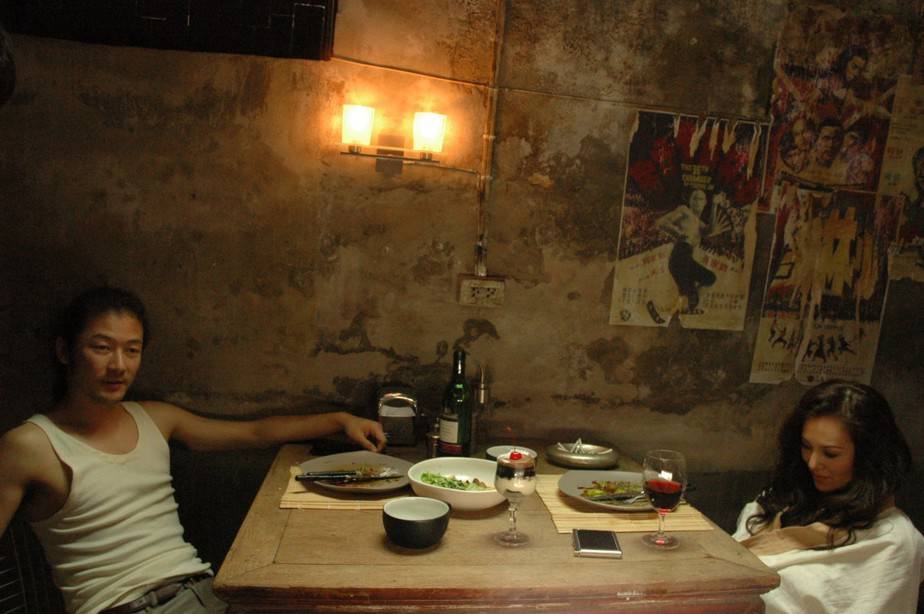

Kyoji (Tadanobu Asano) is a cook working in Macau who has been having an affair with the wife of his boss. As a means to redeem himself in front of him, he follows the order of his boss, who wants his wife to be killed and Kyoji to leave the country afterwards.

After the deed is done, Kyoji makes his way to his new life in Phuket, Thailand. On his journey, he goes through many strange encounters with the small crew of the ferry he is on. In the enclosed space of his cabin, with the lights barely working, he finds himself haunted by the things he has done. However, his guilty conscience is not his only problem since his boss has decided not to let him get away unpunished for his lack of loyalty towards him.

The basic plot of “Invisible Waves” seems similar to many gangster films or thrillers dealing with the criminal underworld and the issue of loyalty, as well as punishing those who do not follow the orders. However, in combination with the technique of reduction as mentioned before, the overall film seems to slow down as well starting from the obvious focus on Kyoji's days on the rusted, dark corridors and outsides of the ferry he is on. Cinematographer Christopher Doyle, whose atmospheric camera motions and perspectives have added life to the streets of Hong Kong in the films of Wong Kar Wai, uses very little, almost static images, focusing his framing on the internal struggle of Kyoshi, thus suggesting a far deeper connection of the outside and the inside world, the reality and the (guilty) consciousness of the central character.

Every image seen in the film seems slightly bleached, dirtied, at times rusted like the insides of the ship, the gray streets of Macau which are part of Kyoshi's way to work, and the dimly lit corridors of the ship or the various hotels he stays in, once he has reached Phuket. According to writer Kaleem Attab, the added surrealism in the use of color, sound and image might indicate how the events of the film might be side effects of the character's guilt, of the dream world he has constructed in which he is haunted by the things he has done. While this reading certainly hits right as it fits the context of the film, Ratanaruang's effort allows for many more, one of which leads back to the works of authors like Frank Kafka, an author whose protagonists like Josef K. in “The Trial” or Gregor Samsa in “The Metamorphosis” have an equal weight to carry when it comes to guilt one is unaware or, which might be repressed by the subconscious.

On the ship and the hotel in Phuket, Kyoji walks through the corridors several times, trying to find his room/cabin which, even as he has been in it several times, is still something of an impossibility for him, resulting in him spending much of his time on deck, talking with the mysterious Noi (Hye-jeong Kang) and her son or later on, walking through the streets of Phuket. Considering Rataruang has repeatedly stressed how he thinks of guilt as an inescapable truth of life, one which just seems to grow as one ages, he and Doyle have created a visual metaphor for this truth, the maze of guilt slowly isolating the individual that is always close to losing his/her way completely. The slapstick-humor of the broken appliances in his rooms, the enigmatic conversations, as well as him being locked inside his room at one point, represent something like the inner struggle of Kyoshi, a character swaying between regret, atonement and denial of what he has done, all of which are mechanisms popular among the heroes of Frank Kafka walking the streets of a town to reach a mysterious castle or imprisoned in their room having turned into a hideous creature.

The repeated imagery of the ocean, whether as full shot or as visual representations on the walls of hotel rooms, show the waves of consciousness, the increasing of the water as revelation or catharsis becomes inevitable for Kyoshi, especially as he is also being followed by his boss's henchmen. The biggest enemy, however, is not the opposition hunting the protagonist with guns and weird karaoke performances he is forced to listen to, but the view of the mirror, the wall which has REDRUM sprayed on it. Unlike the Kubrick movie, murder is not an event which will happen since it has already, at the same time, though its foreboding quality remains with the walls, or rather waves, slowly closing in on Kyoshi.

“Invisible Waves” is a irritatingly quiet film with terrific cinematography by Christopher Doyle and a great central performance by Tadanobu Asano. Pen-Ek Ratanaruang has stated how using his time more wisely, taking it and, if necessary, slowing it down has become one the many lessons he has learned over the years working in the medium of film. With “Invisible Waves” the technique defines an attractive tie with the narrative, a film which, like the rising tide, will slowly but surely lure in his audience until it will not let go anymore. In the end, the experience is maybe worth drowning for.

Sources:

Interview Pen-Ek Ratanaruang (2008) http://www.cinemasie.com/en/fiche/dossier/382/, last accessed on: 01/17/2018

Attab, Kaleem (2006) Invisible Waves

Another interview with the director is included in the DVD release of the film by Tartan.