A projectionist and film journalist – and later film tutor – Makoto Shinozaki's 1995 directorial debut “Okaeri” (“Welcome Home”) on first glance certainly appears the work of a novice. However, by the end of the film, there are certainly signs of accomplished filmmaking.

“Okaeri” was screened at Doc Films Chicago:

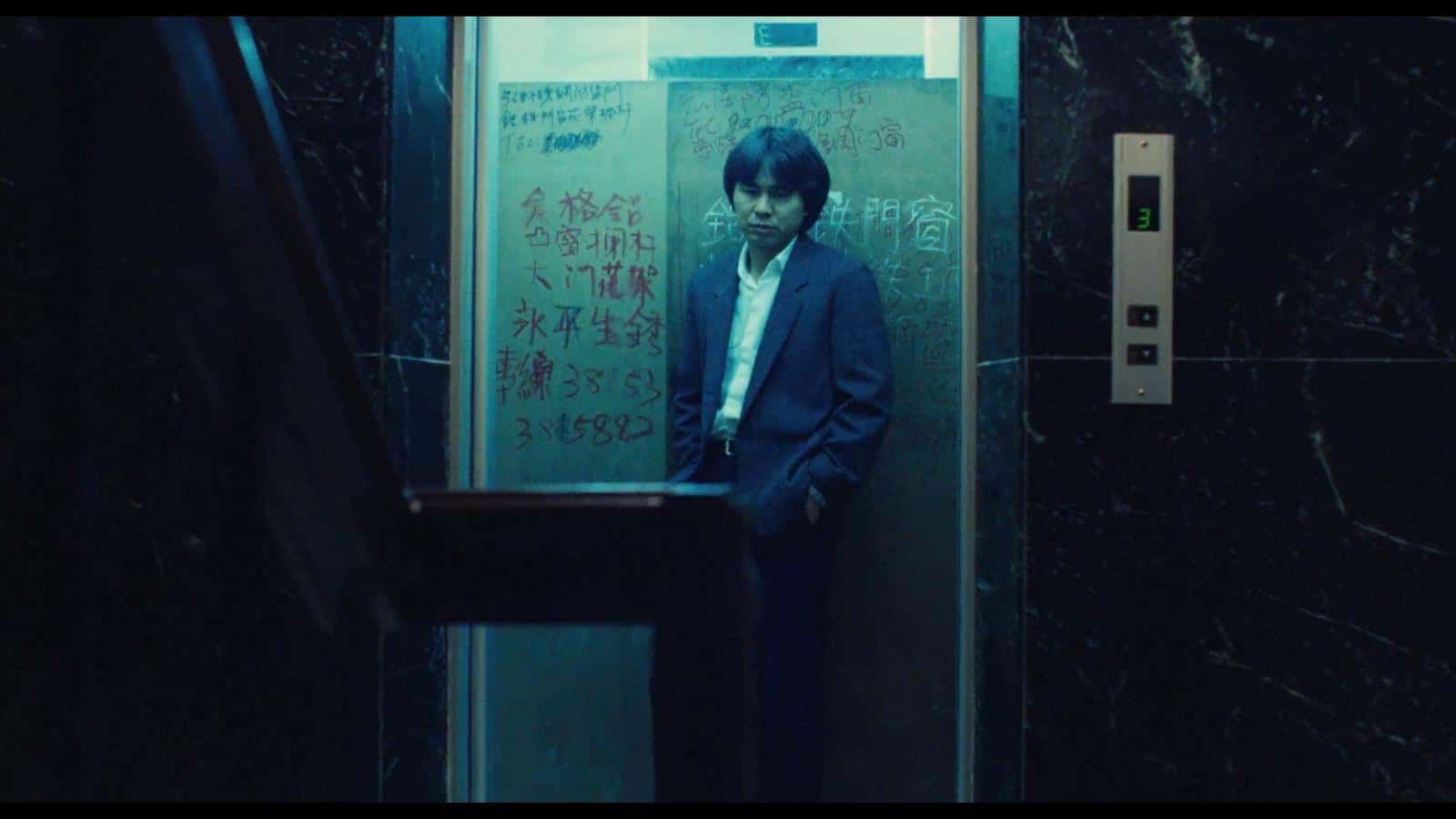

Young married couple the Kitazawas, Takashi (Susumu Terajima) and Yuriko (Miho Uemura), are bang average. Takashi works as a teacher, sometimes working late, sometimes talked into late night drinks, welcomed home by freelance transcriber Yuriko in their modest urban apartment. He is easily led, appearing to put work before his wife, while she quietly waits at home for his return; a fine meal prepared.

But the more time passes, the more Yuriko's stares out the window into the void start to take their toll. Takashi fails to notice her blank stares until it is too late. Beginning to wander the streets aimlessly, she begins to talk of the “organisation” and how all police are fakes, so she must “patrol” to ensure order is kept.

Not wanting to raise alarm just yet, Takashi begins his own research into schizophrenic behaviour, but by this point Yuriko has stolen a car and cruised the streets. Picked up by the police, her returning of the car sees the police drop any charges, but Takashi can no longer ignore his wife's behaviour and now must face the stigma of potentially hospitalising her.

Shot on borrowed film, this feels to have the production values of a mid-90s pinku eiga video movie, with no soundtrack to speak of and background noises picked up over dialogue. Due to obvious budget constraints, this allows for a style throughout the film that gives it added effect.

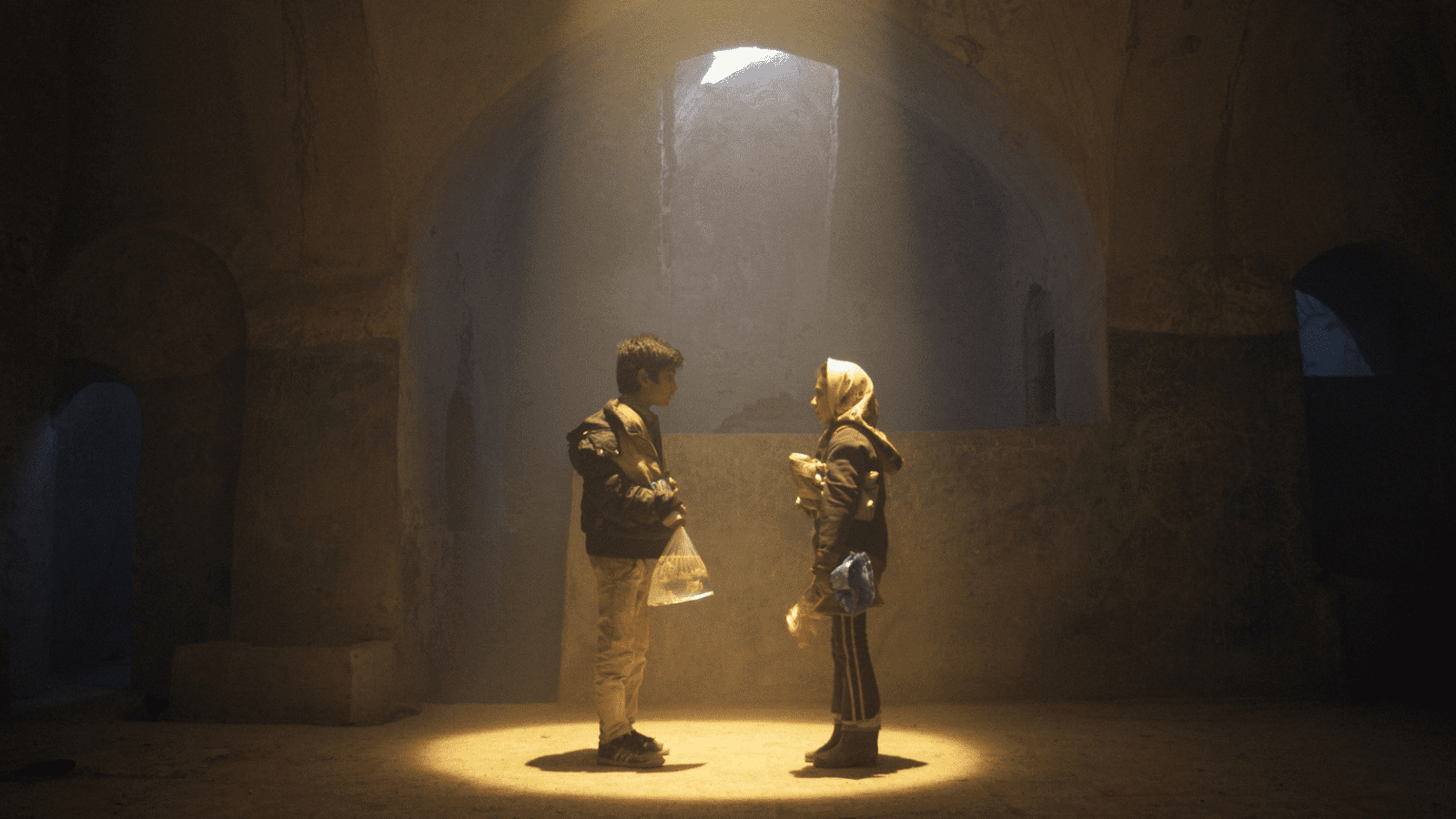

Long takes are shot with static cameras in the vein of observational documentary filmmaking. As such, we are given a cross-section of the marriage. Initially, we are not given any context as to the state of the marriage: no history or back story of the couple and their relationship until later in the film. We have no preconceptions before the camera starts to roll.

These long takes, however, create an intensity within key scenes. The emotion between the two leads comes out naturally as scenes develop, with Takashi holding on to Yuriko for dear life as she goes through waves of emotion. As Takashi gradually calms Yuriko, we too feel the sedative of his embrace.

This approach also helps to show the clear divide building between the couple, with literal and metaphorical walls between them, placing it within a societal context. The burst bubble aftermath of the mid-90s is exemplified by long working hours, divided families and a lack of future. As Yuriko's mental health begins to deteriorate, she looks over old photos of her past as a promising pianist before Takashi's image begins to appear among them. Now, she taps on keys of a different variety and grows increasingly lost in her new prison.

Takashi begins to show signs of guilt as to his part in this deterioration, conducting covert research, hiding away books from work colleagues' view. His behaviour also changes, bringing himself closer to his wife. In this sense, Shinozaki is sympathetic to Takashi: not a bad man, simply one led astray, who is quick to turn his behaviour as problems arise. But the eyes of society still loom. He is reluctant to hospitalise Yuriko, despite doctor's advice. Is this guilt, wanting to cure his wife himself by being a better husband? Or is the stigma of mental health too great, and he doesn't want hospitalisation on his name?

The open end suggests that Yuriko is far from cured by his change in behaviour and rejection of hospitalisation. Will this be something they work through together? Or can Takashi keep the secret hidden at home?

A near quarter of a century on, Shinozaki's debut shows that perhaps necessity is the mother of all invention, with budget constraints leading to some strong filmmaking techniques. However, with his next work, the “Kikujiro” making-of documentary “Jam Session”, he shows that this observational, camera-rolling style suited him well. Sadly, however, his career as a filmmaker hasn't quite lived up to the promise shown in these early works, and we are still waiting to say “welcome home” to this director.