Most women-centric South Korean films set during the Japanese Occupation of Korea tend to look at the situation of the comfort women in wartime. Director Jo Min-ho's “A Resistance”, however, takes a different approach and focuses on the last year and a half in the life of Yu Gwan-sun, one of South Korea's most famous and revered female freedom fighters.

“A Resistance” is screening at New York Asian Film Festival

The film begins with the teenaged Yu Gwan-sun's arrival at the Seodaemun Prison. Flashbacks tell us of her active participation in the organisation and execution of the March 1st Protests, one of the earliest instances of Korean public resistance against the Japanese, where she lost both of her parents and which resulted in the arrest of her elder brother and herself for shouting “Long Live the Korean Independence”. Once at Seodaemun, she is kept in Cell No.8, stuffed in with dozens other women in a room that's barely enough for three or four people at most. Ever the free spirit, Gwan-sun continues to proclaim that she is free as long as she has free thought and refuses to give in to the demands of the Japanese to confess, much to the chagrin of the Japanese as well as Korean-origin soldier Nishida.

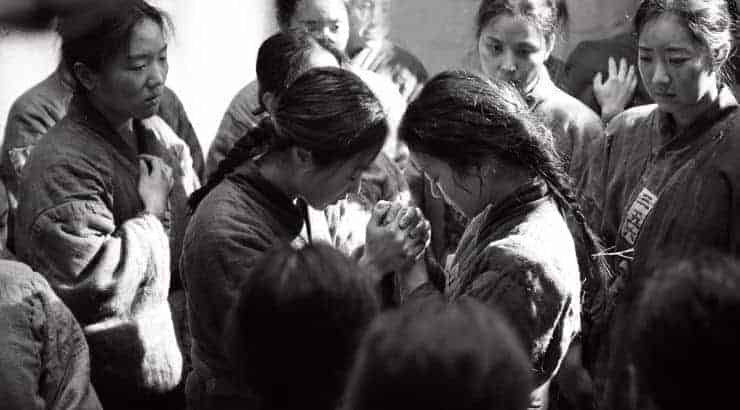

As a history lesson, “A Resistance” works quite well. Yu Gwan-sun's is a story that is very well known within the Korean peninsula but outside of it, she remains a fairly unknown figure till now. The film represents her, her activities and ideologies with reverence. It also manages to capture the atmosphere of the resistance against the Japanese well, as it portrays the living, working and surviving conditions of the prisoners. Those with an interest in history as well as the lives and struggles of freedom fighters in oppressed countries will appreciate the authenticity with which the script, by Jo Min-ho, depicts them. The scenes of the Japanese soldiers mistreating the inmates are shocking and wince-inducing, though the camera tends to shy away at crucial junctures, instead deciding to show the psychological effects of the torture. The cries of “Long Live the Korean Independence” that Gwan-sun instigates, despite all odds, to celebrate the anniversary of the March 1 Protests and her parents' death are particularly touching and rousing.

Having said that, the film does try to play it safe. Reading into Yu Gwan-sun's story, there's plenty more tortures and humiliations that she had to face in prison, but the film tends to show very little of it in an effort to keep the violence down to the minimum. It also does not manage to steer clear of the “all Japanese are evil beasts” mentality that most of the films set in this time period and about similar subject matters tend to carry, particularly those coming from South Korea. Once in a while, it would be appreciable for a South Korean film to show two sides of the coin when it comes to this matter, a bit like what Lu Chuan's Chinese film “City of Life and Death” successfully managed to do. Several of the other side characters also suffer from underdevelopment, including that of Yu gwan-sun's brother.

Technically, it is a very well made film, with DOP Choi Sang-ho's bleak, monochrome cinematography depicting the harshness of prison life accurately. The majority of the film takes place in Cell No. 8, a tiny place overflowing with people and the cinematography makes full use of the tiny space and manages to create a sense of acute claustrophobia. Notice the scene where Yu Gwan-su is punished for being insubordinate and made to stand in a coffin-like box for days. The camera captures the tiny space so well, it nearly makes the audience nauseated. For three very brief scenes, the film moves to colour, two of which are flashbacks while the final scene as life finally leaves Yu Gwan-sun, depicting how life was full of colour before her imprisonment and it wasn't until the sweet release of death that she was truly free again. The music is rousing when required and adequately melancholy for the rest of the film.

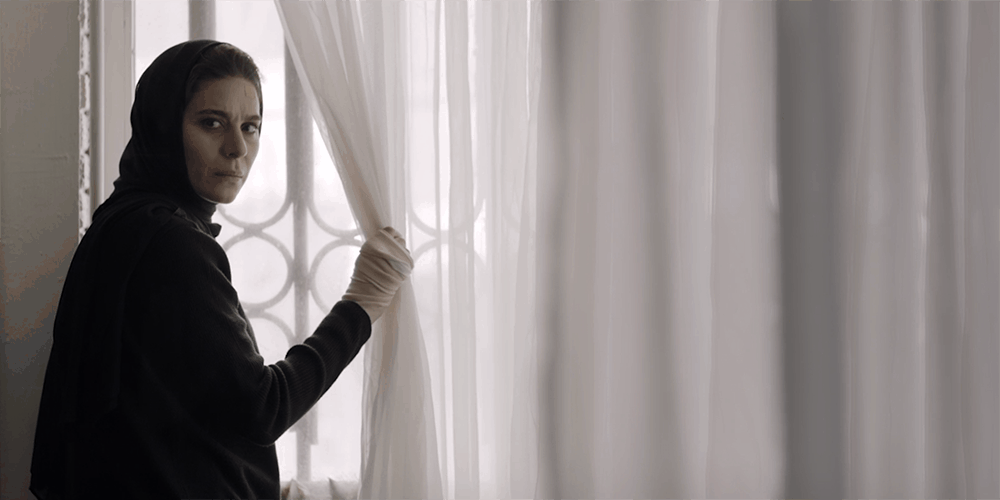

It would have taken a brave actress to portray such a difficult, non-glamorous role, and in Ko Ah-sung, the film truly found its ace! Her performance elevates the film to levels it would have faltered to hit in other actresses' hands. Take the scenes where she talks to Nishida about how even though he is the oppressor and she the oppressed, she is the one living a better life, for example. The conviction with which she delivers her monologues, while having been utterly beaten and humiliated at the hands of her captors is mesmerising. Though most of her supporting cast, including Kim Sae-byuk as her cellmate Kim Hyang-hwa, Ryoo Kyung-soo as Nishida and Sim Tae-young as her elder brother Woo-seok, are each good in their roles, they do not get enough scope as Ko Ah-sung takes centre stage.

The real Yu Gwan-sun was buried at Itaewon cemetery post her death, but her grave is since considered to be “lost” when the site was redeveloped into an airfield. “A Resistance” tries to make sure that her story doesn't get lost in this modern, free world either and is a worthy ode, released on the 100th Anniversary of the March 1st Protests, to the teenager that died for the freedom of the nation.