The Japanese actor Takao Osawa was so moved by Masashi Sada's popular song “The Lion Standing in The Wind”, that he approached the songwriter with a suggestion of adapting it into a novel. Not only that Sada made Osawa's wish come true, but he also wrote the movie script based on the novel inspired by the song, thus, one would believe – completing the circle. “The Lion Standing Still” – all forms of it – is based on a true story about Koichiro Shimada (Takao Osawa), a Japanese doctor who in 1987, motivated by a long-time medical missionary in Africa Albert Schweizer, left the university hospital in Nagoya to join the research team of The Institute of Tropical medicine in Kenya, the country where he found his tragic end. It is indeed a story of big importance that deserves to be told, and yet it is difficult to comprehend what made Takashi Miike to seize for this project and turn it into something very unlike anything he ever directed before, or since.

Buy This Title

“The Lion Standing in the Wind” is a trouble child, the one that after it had suffered from all possible traumas as a toddler, turned into momma's little handful. Admittedly not knowing the song, and never ever having touched the novel, I am sure that the script doesn't deliver half of the promising plot, considering doctor Koichiro Shimada's life. Plus, the song and the novel turned into a script were allegedly inspired by letters the doctor wrote to his fiance Takako (Yoko Maki), also a doctor who stayed in Japan to take over her father's medical clinic on a small island. This written communication is almost completely absent in the narrative, and the bond between the two pretty loosely told. On the honest side, biopics (especially those inspired by a non-classical biopic material) can be nasty to turn into moving images, beginning with the clear concept of how to approach the story development and which attitude to take – analytically sober, romantic, comedic, cynical, intimate or inventive. Takashi decided to be overly romantic, which is like having Tarantino making a documentary about growing daffodils in a hippy commune where the most exciting thing that is happening, you are guessing, is growing daffodils.

The story is told a bit in the now, and plenty in the past, accompanied by many voice-overs. So many actually, that the narrators get their fair share of space in the film, diverting the flow of narrative the way corrupted city-planners change the look of settlements. The viewer gets mercilessly bounced from one episode of Koichiri's life to the other, from his childhood, to the student days and his work in the Nagoya hospital, not being sure why some bits were granted relevance. Maybe the heart-breaking tunes of (an otherwise genius composer) Kôji Endô's original movie score was meant to help deliver answers, but it resonates more as the “South-American telenovella meets German soap opera somewhere on the Bridges of Madison County where they are greeted by Out of Africa, to settle on the film's proper geographic ground”. With a truly stellar act, Miike Takashi's know-how and his faithful collaborators – the director of photography Nobuyasu Kita, the man behind “Fist Love”, “The Blade of Immortals”, “Laplace's Witch”, “The Mole Song: Hong Kong Capriccio” or “13 Assassins” with his immaculately well calibrated long shots, and one of the few reliable editors of Takashi's movies Kenji Yamashita, this shouldn't have happened.

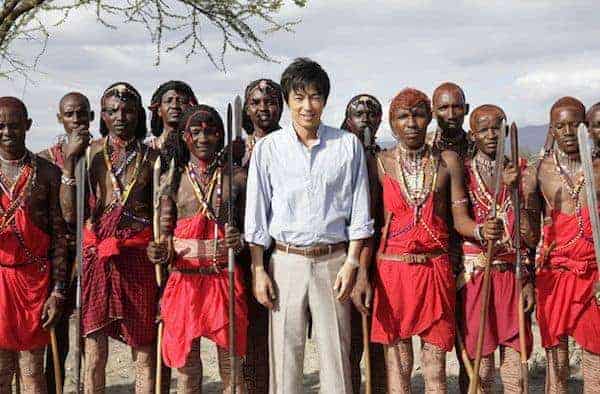

Pathetic tones have never really damaged the Japanese master's movies to this extent, because he usually knows how to build them into a compact story, no matter the core of a film's subject. What happened in “The Lion Standing in the Wind” is an overload of emotion-laden lines. For instance, Koichiro is comforting amputees in the Lokichogio hospital in the middle of a region afflicted by the Sudanese war where he was sent as a helping doctor for a month, with Rocky Balboa- like platitudes. Needless to say, they even work wonders. It doesn't get better seeing the Japanese medics visiting a Maasai village, where they try to fit in by joining in the ritual dance, and that scene gets almost as bad as Johnny Knoxville and Jackie Chan singing Adele's “Rolling in the Deep” with a Mongolian village in Renny Harlin's “Skiptrace”. Looking back at the legacy of a man who left his more or less comfortable life in Japan to heal children scarred by war, the question if it was necessary to turn him into a guy who screams “Ganbare!” through the night, because he believes to be a lion, seems inevitable.

The lion reference in the film comes from a dialogue between Koichiro and the director of The Institute of Tropical Medicine, doctor Masayuki Murakami (Renji Ishibashi), when the latter remarks that lions are pimps because they make their women hunt for them, to which the doctor prodigy simply retorts: “That's a lion in pride. A lion outside his pride leads a harder life.” That answer simply resonates with wrong messages, as many other lines in the film. “The Lion Standing in The Wind” is one of the examples that you can't make a good movie based on a bad script.

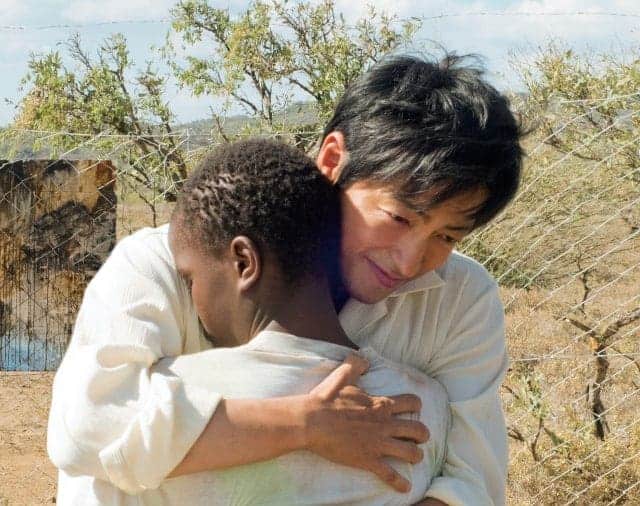

The film also aims focus on a young nurse Wakako Kurano (Satomi Ishihara) who dedicated her life to the rehabilitation of children soldiers in Kenya. Credits are due to quite literally all African actors whose names are not listed anywhere, particularly the boy playing heavily traumatized Ndung'u, who witnessed the death of his parents before being abducted by the same men to join their armed forces, heavily drugged. Memorable is also the English actor Nick Redding who's occupying the role of the Lokichogio hospital's chief medical officer. There is a fine moment in the film's long ending, when we see Koichiri as a child getting Albert Schweitzer's book “The Father of Africa” as a birthday present from his parents, which is one of the most relevant filmic statements in “The Lion Standing in The Wind”.