“Now or before?” is the puzzling reply that Ga Yin, the protagonist of Fruit Chan's “The Longest Summer” gives to his boss when asked the mundane question: “Ga Yin, you have any goals in life?”.

“Now or before” could also be a good synopsis for this movie, as it encapsulates the mood of a precise moment in time and highlights the turmoil created by that historical crossroad.

Bagpipes play Auld Lang Syne, while a metallic voice recites empty words: “The Corps' disbandment is also a time for reflection and pride in all that the Hong Kong Chinese soldiers have achieved”. “The Longest Summer” starts solemnly with some real footage of the disbandment of the Hong Kong Military Service Corps, three months before the Handover to China. When the camera pans over the Corps, we can spot the protagonists of the movie; they are those very soldiers that are just about to be made redundant and unemployed.

Suddenly left without job and purpose, Ga Yin (the terrific newcomer Tony Ho) and his little group of ex-army friends keep meeting up and sharing concerns about their future and their difficulties in finding a place in the unfamiliar environment. One of them is now a security guard in a bank; others handle advertising leaflets or plan to move to Mainland. However, temptations to go onto the illegal side are strong. Ga Yin's younger and cockier brother, Ga Suen (again, a very good Sam Lee) is a low-rank member of a triad and with his exuberant insistence, manages to convince Ga Yin to join him and work as a driver for his boss. In denial at first, Ga Yin insists it's a job like any ot,her, but it doesn't take long to start thinking gang-style. Indeed, in no time the two brothers are organising a bank robbery, involving also the group of ex-army friends. The robbery takes an unplanned direction and its consequences will shape the second part of the movie, where also a minor plot will develop, following Jane (Jo Kuk), a young woman the two brothers had met by chance, earlier on in the story.

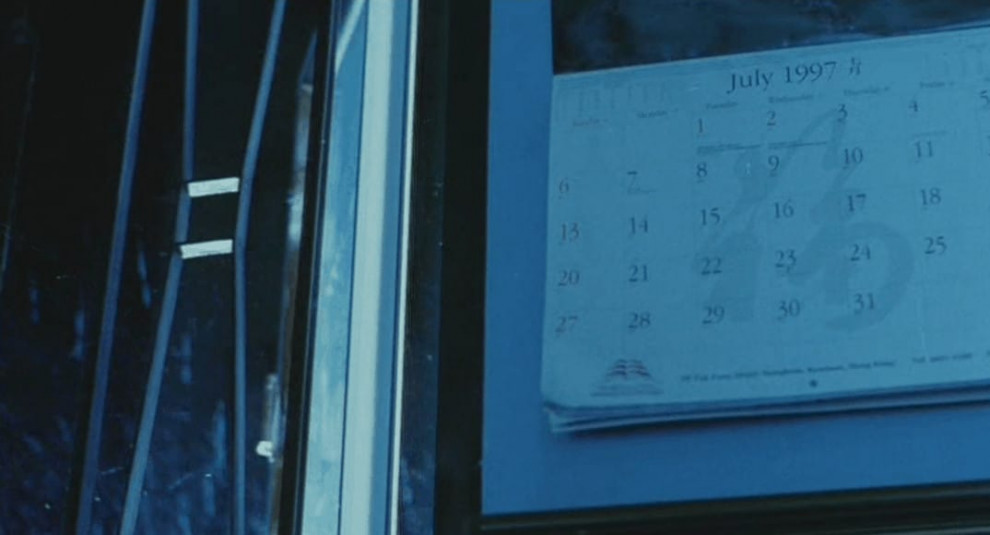

Fruit Chan ‘s sophomore work after the acclaimed and unique “Made in Hong Kong” is a film that shares similar social concerns and same poignancy and relevance with the previous one, but it speaks a less “arty” language and is set in a very precise place and time. The long Hong Kong season of the title is the summer 1997 that started with the dismissal of the Hong Kong Military Service Corps, followed by the official Handover Ceremony on the 1st of July and – on the morning after – the rapid deployment of the People's Liberation army troops.

Albeit a long announced event, it was a lot to take in for the city of Hong Kong and its people; the anxiety and the uncertainty, but also the expectations, generated by this major turning point affected the entire population of Hong Kong. However, Fruit Chan chooses to express it through the capers of the dispossessed working class, a point of view that will pop again in many of his future works. Here the author chooses a very concrete and effective example to illustrate the fast dispossession, a group of ex-army that are swiftly made unemployed (and unemployable), and left with very little usable skills at an unsuitable age, in a society that is more and more ruled by money and youth.

Using a cinematic language that is very familiar to the audiences, Fruit Chan subverts it from within. The rhetoric ingredients are all there; the gangster movie tropes, a good handful of melodrama in the collage of happy camaraderie moments over the Auld Lang Syne, and some pleasant touches of comedy here and there, like the watermelon incident. All may look customary fair, but there is no heroic bloodshed or honorable brotherhood here; in fact, there are no heroes at all.

Like in “Made in Hong Kong”, the gangster-ism of “The Longest Summer” is very rooted in the social and economical context. Values are mutating quickly – almost overnight – and the inability to adapt to an unpredictable future is the main theme of this movie. Like the protagonists, a whole slice of Hong Kong society struggles to keep up with the fast-changing social landscape and a shift in moral values is a direct consequence of this socio-economical instability, affecting – again – the dispossessed layer of society in its race to keep up with capitalism. Ga Yin's family consider him a looser while praising Ga Suen's resourcefulness in joining the triad and bringing home money, but quite the opposite, the mob boss' family values seem to be more stern and hypocritically moralistic.

“It's a new world out there. Seems like Hong Kong became a baby overnight. You and I, we are old babies”.Dialogues in “The Longest Summer” are short and sparsely placed in the 2 hours and 8 min of running time, but they are a subtext galore; almost every line in the movie is pregnant with wisdom and innuendos, despite the simplicity of the exchanges. Ga Yin, Ga Suen and their comrades' chats, and the boss' sermons are penetrating darts, integrating the powerful and pop imagery of the film.

A personal favorite, “The Longest Summer” has aged well. It is bitter, nihilistic and sadly current, as people of Hong Kong are now out again, on those same roads of the 1997 deployment parade, still struggling to make sense of the “before or after” conundrum.