How do you document a film with film? How is it possible to use the technology of writing with movement to incorporate everything on a film strip, and everything that surrounds it (the theater, audience, social-political context, etc)? Director John Torres' “People Power Bombshell: The Diary of Vietnam Rose” is a film that attempts to accomplish this mission.

According to the director's statement, he found the footage of “Diary of Vietnam Rose” under the bed of a former Filipino sex icon. The film was shot by the “self-professed Messiah of Philippine Cinema” Celso Ad Castillo. Castillo was shooting the film when Oliver Stone was finishing “Platoon” on the same island. The consultant in Stone's film, Richard Boyle, also had a part in “Vietnam Rose”. Meanwhile, on the main island, the People Power movement has already started. Marcos and his gangs were ousted. A democracy was reborn.

“People Power Bombshell: Vietnam Rose Diary” is screening at Across Asia Film Festival

According to Torres, they shot new footage and interviewed the cast and crew of “Vietnam Rose” to make a portrait of “a tormented young actress who never got to realize her dream of being a star in the 80s”. Perhaps following the spirit of Jean Rouch, Torres invited some of the cast members to watch their unfinished film on a big screen, and asked them to improvise dialogues for, and commentaries on different scenes.

Torres uses sound very interestingly in this film. He blatantly disregards the realist convention in mainstream filmmaking. When watching a regular film, we will often assume that the voice of a character will match with the figure of the character we've been seeing on screen. A white guy in the Philippines should probably be speaking English in a male's voice. Torres throws this convention into the water half way in the film. In one scene where an American Vietnam war veteran is arguing with a Filipino man, Torres lets the veteran speak in Tagalog in a female's voice. He also switches the voice of each character constantly. This strategy pokes hole in the realist facade created by the cinematic language. This creates a world where everything is in flux, nothing will attach to anything forever. It is a world where identity is constantly shifting. One's voice is often a powerful indication of one's identity. It projects to the world who we are, or who do we want to be. If one cannot be certain that one will be speaking in his or her own voice from moment to moment, what does that say about his or her identity?

It might be a cliche to link every independent Philippine films back to Tahimik. Yet, his presence is constantly felt throughout this film. The imagery of typhoon at the beginning and end of “People Power” transports back to Tahimik's “Perfumed Nightmare” (1977).

Closer to the end of Tahimik's masterpiece, the protagonist played by the director himself is invited to a “high society” party, in which he is surrounded by all the important Western politicians (played by Filipinos wearing masks). Despite being belittled and outnumbered by these grotesque figures, Tahimik fights back. In a fabulous fashion, he blows them away with the typhoon created by his mouth. After this harrowing experience, he transforms an unused gas tank into a space ship and flies back to the Philippines. For Tahimik, there is a dichotomy between the East versus the West operating in this sequence. After defeating the West with the wind from the East, the main character in “Perfumed Nightmare” renounces his fascination with the West (this fascination is embodied by Tahimik's admiration for the rocket scientist Wernher Von Braun) , and returns to his hometown. (Of course, Tahimik's politics is more complicated than the simplistic “clash of civilization” philosophy. Throughout the film the character played by him is constantly making connection with the old and traditional within the West. Through his eyes, we see the similarity between the Jeepneys in the Philippines, and the church's onion-shaped dome in Germany.)

Typhoons also occur in “People Power”. Two, to be precise. We first see one early on in the film, and we are closer to the end when we see another one hovering on the sea. However, typhoon is not an anti-colonialism weapon in Torres world. It simply hovers on the sea. The characters acknowledge it, yet they don't do anything about it. If Tahimik incorporates natural sound of wind blowing to transform a natural phenomenon into a symbol for a desirable historical process (decolonization, for instance), Torres uses digital effects to create an indifferent natural phenomenon. It simply exists. It is part of the natural world, but keeps its distance from the human historical one. We humans can only stand on the shore and contemplate it.

Moreover, although indebted to Tahimik's art, “People Power” is quite different from the worldview created by Tahimik. In “Perfumed Nightmare,” there is still a relatively stable Filipino identity. There is a place for Tahimik to go back to at the end of the film. On the contrary, “People Power” is dislodging the idea of a essentialized identity through is intricate sound design.

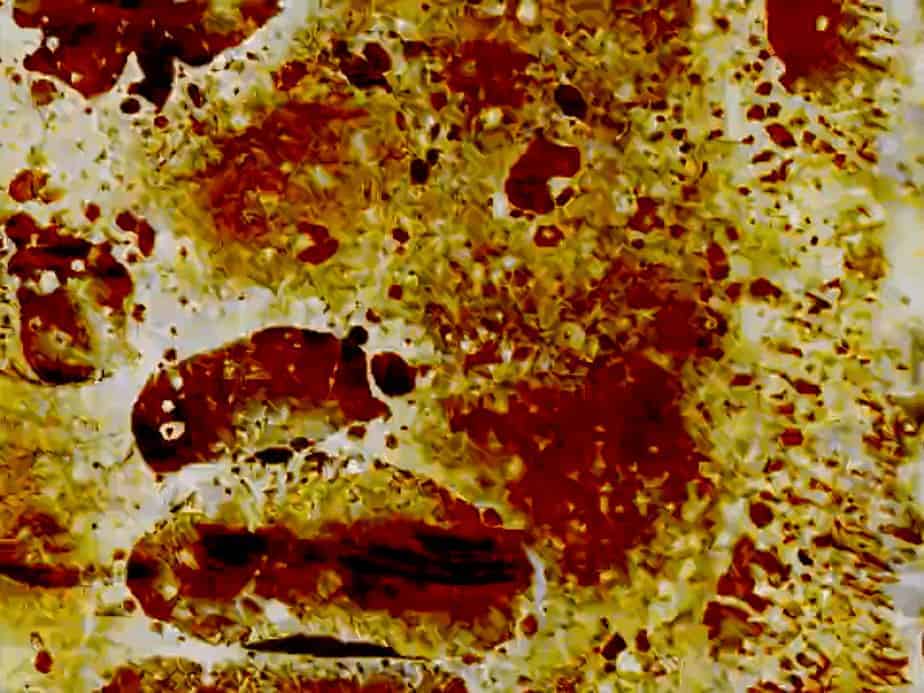

“People Power” is a fascinating account of the nature of cinema. Torres not only lets the cast of the original film improvise for the footage, but also keeps their comments of the footage in the final product. In other words, the film incorporates an audience of itself within itself. In addition, Torres makes the quality of the film stock of the original film part of the “performance” of “People Power”. The degradation, distortion, or to put it simply the material of the old film stock becomes another character in the film. We have to see them constantly intervene or participate in the actors' performances on screen. Perhaps it is not surprising that at the end of the film, Torres gradually zooms in on the film itself, and for a while all we can see is that shapes, dots, and lines exist within the film stock. The noise becomes the message. It might be argued that, Torres creates a situation where the audience needs to contemplate on the material nature of the film; not unlike when the characters cannot do anything with the typhoon, but looking at it.

Moving through the history of the Philippines, the legacy of the national cinema, the nature of filmmaking, and the ontology of film, “People Power Bombshell: The Diary of Vietnam Rose” is one of the most exciting films we've seen recently.