Within the hearts and minds of many non-Westernised peoples wages an eternal generational war; between the young and the old, the old and the new, groups struggle amongst themselves to mark their own cultural identities. Pema Tseden has been one such voice caught in the crossfires of such a struggle with his films chronicling the Tibetan way of life with excruciating detail against an invisible yet potent threat of modernization always lurking on the fringes. With his 2011 portrait of humdrum mundanity he pushes both the limits of pacing and audience patience to the extreme; on its surface “Old Dog” offers nothing more than simple thoroughfare with as bare-bones a plot as possible, but descend deeper into the film's (albeit overt) symbolism and a wealth of rumination is up for grabs.

“Old Dog” screened at Vesoul International Film Festival of Asian Cinemas

After a spate of dognapping across the village, Gonpo sells his father's Tibetan mastiff of 13 years to Lao Wang – a local dealer whose “merchandise” ends up on the Chinese black market – under the seemingly false pretense of saving it from a similar fate. Furious with his son, Akhu enlists the help of his policeman relative Dorje to buy it back. Threats continue to linger regarding the mastiff's safety with each successive sale refusal Akhu makes, coming to the point where he is more willing to set it free instead of selling; even then his herder manages to find its way back to him, no thanks in part to Gonpo's meddling. Meanwhile there are concerns as to why no child has come from Gonpo and his wife Rikso's three-year marriage, so the nomadic patriarch insists the two visit the hospital to determine the problem.

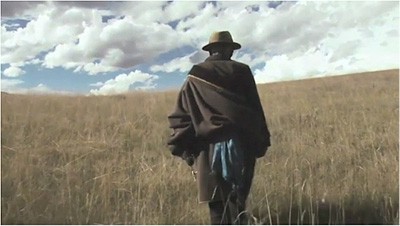

A tale as quiet and as in situ as the world around the narrative, a lifetime passes by between two points of any given moment; such is the speed at which “Old Dog” ambles along its near-90 minute runtime, anyone would be forgiven for feeling as if nothing at all is happening. But, as with any other Tseden picture, this couldn't be further from the truth. Fiction intertwines with life; the glacial flow of the day-to-day mirrored not just in the arduous pacing and editing but also in drawn-out passages of the nomadic family doing very little (too often do we cut to observing them watching what appears to be the shopping channel). Time stands still in this world far-removed from the hustle and bustle of modern China; cinematographer Sonthar Gyal captures this with excruciating detail whilst giving realist photography a whole new foundation for 21st-century filmmakers to work on.

As a result, Tseden's film almost transcends the simplicity of its own narrative. Using Akhu – the stubborn, physically-aged shepherd whose very existence seems to be verging on the brink of extinction – as a vessel for his own frustrations, Tseden bemoans the current state of things. Gonpo, a drunken layabout who cannot commit to anything he does (he frivolously spends money on a pool game he spends less than a moment playing) is a disappointment to his father whilst his fragile masculinity surfaces only to his wife.

The real criticism, however, is saved for the region's omnipresent yet always invisible neighbour to the immediate south. Tseden does not shy away from vocalising his disdain either but instead of pulling punches it all sounds like the ramblings of a man refusing to let go of traditions; through Akhu cries the voice of his entire world, one which sees the “guards of the nomad” – the scruffy, matted elderly titular dog for example – being shipped off merely for aesthetic pleasure and status symbols. It is through the silence and the dullness where Tseden is at his loudest, and here he is truly deafening.

For all “Old Dog”'s symbolism and its immaculate reconstruction of fourth-world existence, however, the film is incredibly taxing and a laborious watch. Plodding along (the term here is an understatement) at an elderly pace with little emotion from its cast or script, we as an audience endure the journey from a cold distance courtesy of Gyal's framing; we are never fully invited into the film's world lest we bring our corruptible influence further into the village. There is very little opportunity for an emotional investment with the story being told – even the tragic relationship between Akhu and his dog feels like a world away – and though it can be argued such an investment would be superfluous in such a stone-faced world the lack of a connection only makes this even more of a difficult film to get through.

The rewards for reaching the devastating end however are indeed endless. Tseden is the only Tibetan voice allowed to create in China and to gain access to where he has come from is nothing but enriching. That such hardships are endured for the sake of preserving a lifestyle seldom changed for centuries is too often overlooked in our endless romanticising; “Old Dog” is an eye-opener which enhances the clarity of the real picture behind such mythologies. As rough and rugged as the town itself this is cinema at its most stripped-back, most honest, and above all most diligent.