Oft times, documentaries portray an issue or situation peculiar to a certain region or country, which is known to all within that region but not many outside of it are even aware of. Iranian director Behzad Nalbandi tackles something similar in his latest documentary “The Unseen”.

“The Unseen” is screening at Vesoul International Film Festival of Asian Cinema 2020

Homeless people in Tehran, the capital of Iran, are called Cardboard People because of their desperate habit of practically living out of and sleeping in cardboard boxes. When foreign dignitaries or government higher-ups visit the city, these homeless people are removed from the street and put into detention centres. While the males are released after a few days, the women never get to enjoy freedom again, spending the rest of their lives in such detention centres amidst terrible conditions. Through a friend of his sister's who worked there, director Nalbandi was able to gain access to one such detention centre and talk to five women, his recorder handy, who had been brought into the centre and had never seemed to get out of, even though some did attempt to escape.

Nalbandi's conversations with the women, ranging in ages between 27 and 54, draws a terrible picture of the situation of women in the country, especially those that find themselves homeless and on the street through various reasons. He is not particularly interested in the steps the government, society or even their families take or fail to take that lead to these women's situations going from bad to worse. Instead, he is more interested in the human stories of the women themselves, with the chief topics of the conversations being the women's drug addictions, their relationships with their respective families prior to becoming homeless, their love lives and how they ended up on the streets. Drug addiction is, more often than not, the root of all the problem which is not surprising, considering how easy it is to procure Schedule I drugs like heroin and hashish in the region.

The conversations are broad and cover a lot of dark ground in each women's lives, talking about their descent into prostitution, drug abuse, thievery, sexual abuse and even being drug mules under duress or willingly, but also shows the more gentle, more human side of the females too, as they talk about the loves of their respective lives, the adulations they have for their husbands who they have not seen for years or parents who shunned them and caused them to be homeless. The fact that these women have hopelessly accepted their fate and know in their hearts that they are destined to stay in these centres for the rest of their lives is quite heartbreaking. It also succeeds in drawing a stark image of the terrible living conditions within these detention centres that the women learn to survive in.

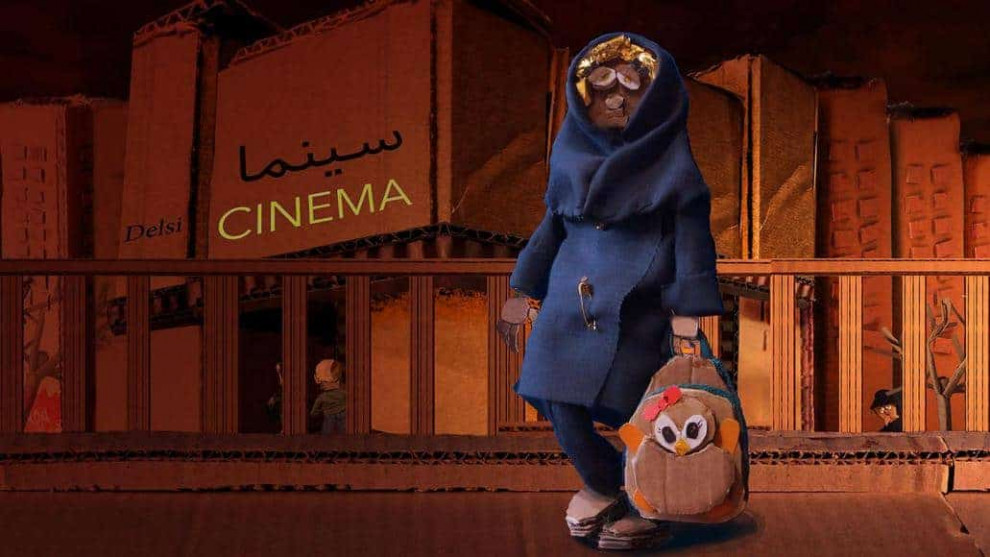

Since Behzad Nalbandi had to promise not only the women interviewees but also his sister's friend to not shoot any video for his interviews to protect their anonymity, the film utilises stop-motion animation with the help of cardboard puppets – literal cardboard people – to depict the interviews, which is quite well done. All the women are portrayed uniquely and distinguishably, giving each of them traits and personalities of their own. Ata Ebtekar's music is a solemn companion. Nalbandi's own editing keeps the film concise at a brisk 61-minute runtime.

For documentaries that deal with such important and otherwise disregarded subjects, it feels almost disrespectful to the interviewed subjects and the filmmakers' work to talk about any shortcomings the films themselves may have and “The Unseen” does certainly tend to make you feel that way. So talking about the lack of covering the government steps that are being taken for these women, or the lack thereof, or even the sometimes repetitive nature of the conversations does not do any good. Instead, the film should work as a platform to make the much wider audience, human rights workers or humanitarian services aware of the dire situation these women find themselves in and to open conversation about them.

The dire situation is explicitly highlighted when, in the final scene of the film, it moves to real-world video and takes us on a short ride around Tehran. One would except it to show lots of Cardboard People in the streets living out of or sleeping in their cardboard boxes, but instead the absolute lack of a single such person is indeed chilling, only serving to make the viewer wonder just how many of them have been moved to detention centres that they will never come out of for the rest of their lives. And when the final intertitle card comes up on screen to reveal the fate of the five women just five years since the interview, the film's urgent call for help becomes almost deafeningly loud and unbearable.