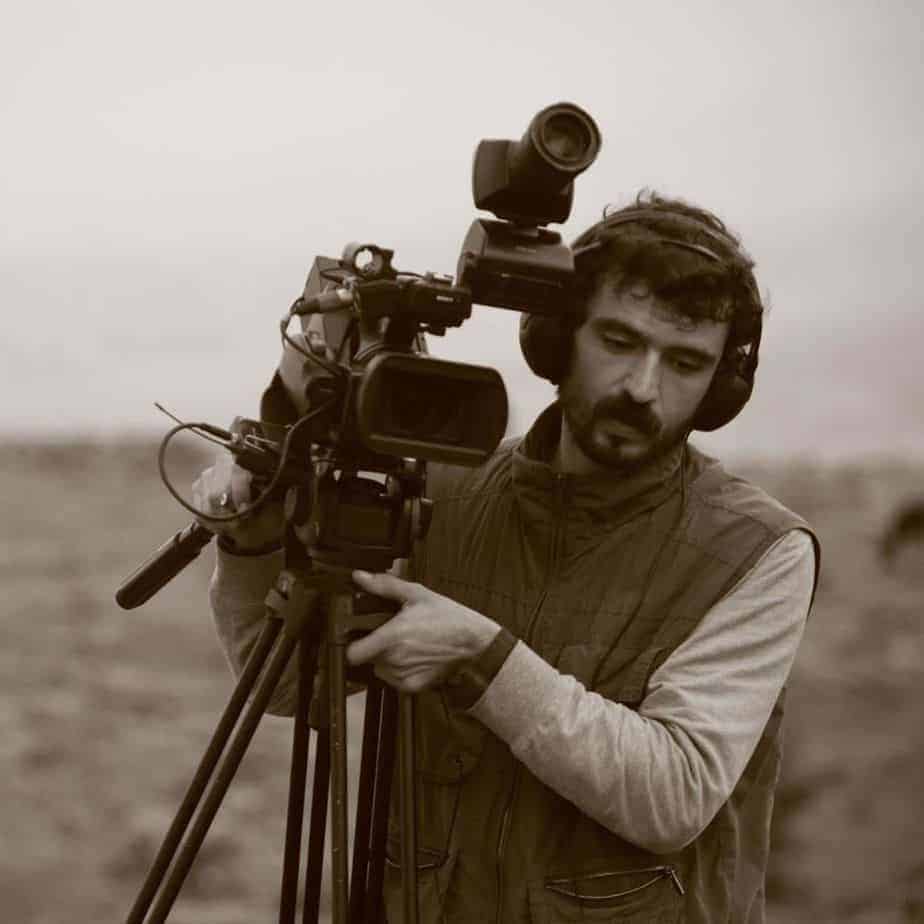

Ersin ÇELIK (1984, Turkey) is a writer, journalist and filmmaker. In 2006, he graduated from the Physical Sciences Teaching Department of the Samsun OMU. He then started working as a journalist, which often led to arrests and prosecution. Much of his work as a writer and filmmaker focuses on conflict areas such as Rojava and Kurdistan. The End Will Be Spectacular is his feature film debut; it premiered at the 2019 Kolkata International Film Festival.

On the occasion of his debut screening at International Film Festival Rotterdam, we speak with him about Kurds, ISIS and Erdogan, Ocalan, shooting near war zones, the Rojava Film Commune, and many other topics, in a rather political interview that definitely deserves a watch.

What is the situation with the Kurds, ISIS and Erdogan's Turkey at the moment? What about PKK? What are the central demands of Kurds and how close to accomplishing them they are at the moment?

The situation in Turkey is bad, not only for the Kurds, even not only for people, rather, it is very bad for everything beautiful. It is ruled by an administration that is involved in crime and corruption, and as far as it can be from democracy and law. Even the Kurds rights of electing and being elected are taken away. For the last two elections, elected mayors are arrested and other “trustees” assigned instead. If 10 people gather, hundreds of police forces would attack them. Tens of thousands of Kurds and dissidents are jailed, and so on ad so on.

On the other hand, attacks and military offensives are carried on daily in order to eliminate the democratic status that Kurds have gained and tried to develop in Rojava. The AKP-MHP alliance is threatening Europe with refugees, and changing the demographic structure in Kurdish cities that it now occupies.

The demands of the Kurds are very clear. They want to rule themselves by themselves. So they want democracy. They want to speak their own language, and to get education in it. They want equality, justice and women's freedom. In their country divided into four, they want a common democratic life with the other people and beliefs they live with. Because of all these demands, they have to defeat fascism. They are close to realizing that. And what I can see, despite all the obstacles, is that they are very determined.

Is Ocalan considered a hero? What is your opinion about the role Greece played in his arrest?

In my opinion, it would be better to define Öcalan not as a hero but rather as a political and ideological leader of a people. Heroisation sometimes means removing from daily real politics. However, since February 15, 1999, Öcalan has been the leader of a people in an island prison, held in isolation that has rarely been seen in history. Despite this, he is a leader that can affect real political developments not only in Kurdistan or Turkey, but the Middle East and the world. The vitality of what he suggests as a solution for the Kurdish quest and all the chronicle problems – quests of the Middle East; Democratic Confederalism, meaning less state and more democracy, can be seen better today.

Every Kurd knows the role of Greece in the arrest of Öcalan. Of course, not only Greece but many local and international powers played a role in his arrest. Greece was known for the Kurds within a concept of “friendship”. I guess what was done had nothing to do with friendship. The struggle of a people or community for the universal rights – which is still going on – is being sacrificed by the states' interests. The most pragmatist and two-faced power in this, is the EU and its institutions. Whereas the EU can play an important role in the democratic-peaceful solution of the Kurdish quest.

Can you give us some detail about the Rojava Film Commune and the role it played in the production of this movie? What is your role within the Commune?

Rojava Film Commune made this film. The Commune was established in Rojava in 2015. So far it has made many short films, documentaries and music videos. Moreover, it also held a film festival. With its project “traveling cinema” it also organized film screenings for both villages and children. It provided both logistic and human resources support to tens of filmmaking crews coming to Rojava. Now, apart from this movie, there are two documentaries directed by different commune members. These are also about to end.

Particularly for this film, ‘Ji bo Azadiye' or ‘The End Will Be Spectacular' not only the Film Commune, but dozens of institutions and hundreds of people in Rojava participated in its production process. Nearly 100 of cinema lovers, cinema artists and workers, worked voluntarily for both pre-production and the shootings (about 6 months). For example, a very large group, whose main field is not cinema, such as neighborhood councils, women's and youth communes, public order and security forces and civil defense units in Kobani, was decisive in the emergence of this film.

My role in the commune is not just making movies. All of our friends have a responsibility to improve the collective work as well as to develop Kurdish cinema. We must both make films and create the infrastructure institutions of the cinema in Kurdistan. More importantly, we want to develop the art academy. Of course, we also have collectivism problems. But we believe in collective work and communal life. And we are trying to improve the communalism within ourselves.

How did you end up shooting this particular story and how did you come in contact with the survivors? Was it difficult working with them for the movie since they are not trained actors?

I have been a journalist actively working in Turkey, Syria, Iraq and Kurdistan for more than 10 years. While I was a reporter on the one hand, I made short films and documentaries on the other. This movie is the first feature film I directed. While the war that is the subject of the film was going on, I wrote the first sentences of the script. We had a discussion group for the script where we discussed about every stage of the script. During the scenario development process, we were able to get in touch with 4 of the survivors. We spent a lot of time with them and recorded all.

One of the most important reasons why we chose this story was because the diary was written in Sur. Secondly, people were burned in the basements of some building, and these events were broadcast live on TVs. Nearly 300 people were burned alive in the basements of buildings in Cizre. A whole history was destroyed in Sur. And while all this was happening, the world just stood back and watched. There were massacres in the same geography years ago. Many people and beliefs were slaughtered. Mass migrations occurred. So our film's release is also a critique of this silence.

It is always difficult to work with untrained actors. But it would be much more difficult to work with trained actors – professionals in this movie. Two people who participated in the resistance of Sur (Khaki and Shervan the Pirate) played themselves in the movie. Most of the other actors were young people who had participated in the war against ISIS or grew up in war. Naturally, they were not actors, but they had real feelings and real experiences as well. So I asked the actors not to act. Actually, I tried to make them be themselves, act like themselves, talk like themselves. I think if we worked with trained actors, the movie would not have its current success.

How close to the actual events is the film? How does Sur looks like at the moment?

It is based on real events as much as real people. To a large extent, the real narrated stories from the survivors and the diaries kept during the Sur resistance formed the basis of the script.

Our location was a neighborhood that was largely destroyed during the Kobane resistance. Just like Sur. So, we knead both the story, the actors and the reality of the place with our imagination. It is the cinematic reproduction of reality. We were neither drowned in real life nor really detached from reality with imagination.

Curfew still continues in a part of Sur city. The biggest destruction in the historic Sur district was actually carried on after the end of the war. The destruction after the war is ten times bigger than what occurred during the fights there. They took revenge from the earth, the stones, and the city. This genocide, spread over time, is not only against a people, but also its history, past and future. For example, just as the historical Hasankeyf is now destroyed with dam water, the historical Sur district was also destroyed with excavators.

During the shooting of the film, there was a great battle against Isis in Raqqa City and the Turkish army began to bomb Afrin. How dangerous was it for you shooting there, and how did you handle the danger?

Yes, similar to what's happening now, also then, on one hand there are big resistances, on the other hand, the invasion and bombings of Afrin. We shot the film in the city of Kobani in Rojava, where there is a democratic self-administration experience that attracts the attention of the world. So as long as there is life there, also a film can be shot. It's true that there were risks, still are, but it is our country. We were in danger as much as all the people there. It's not more or less. Our set could be bombed. Me and the core team of the film were ready for anything. We were motivating all of our other friends with the following words, “If there is an attack on our set, we will continue to the fiction film we started, as documentary.” We would have made the film under all kind of circumstances. Perhaps, if we hadn't taken those risks, this film, which we have a lot of people talking about now, would not have come out. Cinema is also part of this democratic struggle. Naturally, it is a field that has risks as much as politics and as much danger as war.

Most of the characters in the film are very brave and willing to sacrifice themselves. Where do they find this power, and why do you think there were those who could not handle it and eventually betrayed their comrades?

We set out to understand the courage and sacrifice you mentioned. As we understand it, none of them were people in love with death. While they knew they had their last moment, they went to death smiling. For example, Çiyager Hevi, the commander of the resistance, while the resistance continues, answers some of the fighters insistently asking, “What shall we do? “What will happen?” with “the end will be spectacular”. How can a person say such a thing while knowing that he might be shattered to thousands of pieces at any moment? The “end” here is not about the war going on there, but it has more to do with the purposes that give them that courage. They do not have a gram of doubt about their purpose. So they would say: killing death! If, really, there is a courage, then of course, there is fear. But a person with a sense of freedom can decide how and when to die, as well as decide how to live. This is something forgotten in today's world. For example, some warriors lose one eye during the war, or another piece – organ from their body. Despite the physical pain, they can make fun of their own injured bodies.

The action aspect of the film is great. Can you tell us a bit about your approach in that aspect in terms of direction, cinematography and editing?

We made some decisions before we starting the shootings. In fact, I think we are behind what we wanted to achieve. Also, we couldn't do everything that we wanted. Because, for example, if something happened to our camera, we didn't have a second alternative.

The image language should have been in accordance to the story. Therefore, the footage was mostly with dynamic movements and handheld camera. We avoided exaggeration, but we tried to record all the real subtleties of a conflict, resistance. We paid attention to details, from the way a fighter held the weapon to the dirt accumulated in the human body.

I have to admit, we suffered a bit and we had some script errors. Because of this, the editing process has long been extended. For a period of 8 months. Both we and the two editors we worked with were very concerned. Especially about the rhythm of the movie. The edit should have been following the script, the cinematography and the story. Thus, it is the cinematic interpretation of the real and documentary aesthetics. We tried to achieve a simplicity that both the Kurdish audience and the world audience can easily understand. Moreover, we watched the first cut of the film, which was 3 hours and a half, in groups of people with many different features and backgrounds. In fact, it was an interactive editing process, an editing process directed – drifted by the audience's sense and reflexes.

One of the most memorable scenes in the film is the one where the remaining Kurds laugh as they are eating chicken. Can you give us some details about how you shot this scene and its significance?

Yes, the scene you mentioned and the one just before it has a special place in the movie. However, those who do not know the war and some details may not understand quite well. For example, while the chicken is caught, soldier-police announcements come from outside. In these announcements, the resistance youth are constantly called for “surrender”. The announcements we use in the movie are real soldier-police voices, from that real time. While the music and the off-screen voices that connects those scenes are also the reall sound of the anthem of Turkish-Islamic nationalism, the “Mehter anthem” coming out from speakers.

In fact, the peculiarity of the scene is a challenge call to the ones who hold power. This challenge is morale – spirits and hope. This is what we understood from the real story. In wars, it's not just about dying or killing. Or, as in the example we explored, the subject is not about defeating or being defeated. Sometimes, in battles, you can die or terminated, but you can win by not surrendering. Like 300 Spartans or Leningrad resistance. Here, too, a state wants to kneel the revolutionaries and the youth of a society. But when they share that chicken, they make fun of their own hunger. In fact, what they make fun of is fascism.

What is the situation with Kurdish cinema at the moment?

The situation of Kurdish cinema is like the situation of the Kurdish cause. Of course, films are being shot, but there is either fascism or war in our own country. Therefore, making a film is difficult, but it is also a different challenge to screen that film and share it with your own society. There are also the films made by Kurdish diaspora. Especially, we can talk about Kurdish filmmakers in Europe. We think that Kurdish cinema can reveal important art works in a fictional cinema ascpect that includes documentary aesthetics. This is one specific feature of us. Kurdish cinema, as long as it is a part of the Kurdish social opposition – struggle, will definitely produce very important art works. Because there is a dictatorship in our country, on the one hand, and on the other hand, there is a democratic, women's libertarian struggle that the world follows with respect. May be not for tomorrow may, but for today; Kurdish cinema should be fed and inspired from this struggle. Refugee stories are a fact, but I think the return of Kurds, who have become refugees, to their country despite everything, is an even more important issue. Or Kurdish cinema can explore – analize the Kurdish women's political-military-cultural leadership and shape its main type or character from these women. If we don't do these, it would be difficult to talk about a Kurdish Cinema, as such.

Are you working on anything new?

Yes, I am working. But apart from the story I am working on, Rojava Film Commune has preparations also for other films.

The story that I am personally working on it is in the development phase of the story. We are developing our story according to the situation in the country. Because we are as realists as much as we are dreamers. We have to calculate where, how and with what possibilities we can shoot everything we write, otherwise it would stay on paper. The characters of the new story, as in `The End Will Be Spectacular` enter and exit into the real events in Kurdistan, with most of the events going on between triangle passing between Iraq-Syria-Turkey triangle and the Iraq-Iran-Turkey triangle. I can say that it is a story where a person finds himself while looking for someone else.