Based on four ghost stories from books of Lafcadio Hearn, Masaki Kobayashi's first effort in the genre and in color film was a huge success, netting him the Special Jury Prize at the 1965 Cannes Film Festival and an Academy Award nomination for Best Foreign Language Film. Eureka presents the film in its uncut, 183-minute-version, in a rather impressive 2K digital restoration.

Buy This Title

The first part, titled “The Black Hair” revolves around an impoverished samurai, who, tired of being poor, abandons his wife who loved him passionately, for a woman of higher statute and wealth. However, soon he comes across his new wife's cruelty and begins missing his first wife's love. Alas, when he finally manages to return, he is met with the worst fate of all.

This part has a highly didactic tone, about the benefits of loyalty and the blights of blind ambition. However, the presentation is that of a horror movie, with the finale being almost grotesque, to the point that one may even feel sorry for the cruel samurai and his tragic fate.

The second story, titled “The Woman of the Snow” focuses on Minokichi, a woodcutter who manages to escape the wrath of a Yuki-onna, in contrast to his fellow, just because he is young and handsome. The ghost, however, warns him never to mention or she will kill him. Eventually, Minokichi meets a beautiful young woman in the woods, and the two of them end up married with children. The Yuki-onna, however, has not said her last word.

This part is more focused on entertainment, although the lesson regarding the value of discretion is also here. The narrative revolves around Minokichi's two meetings with the women, both of which are surrealistic, in fairy tale style, but eventually become tales of unlikely love. Tatsuya Nakadai in the protagonist role is excellent, particularly due to the presentation of his character in the finale of the story.

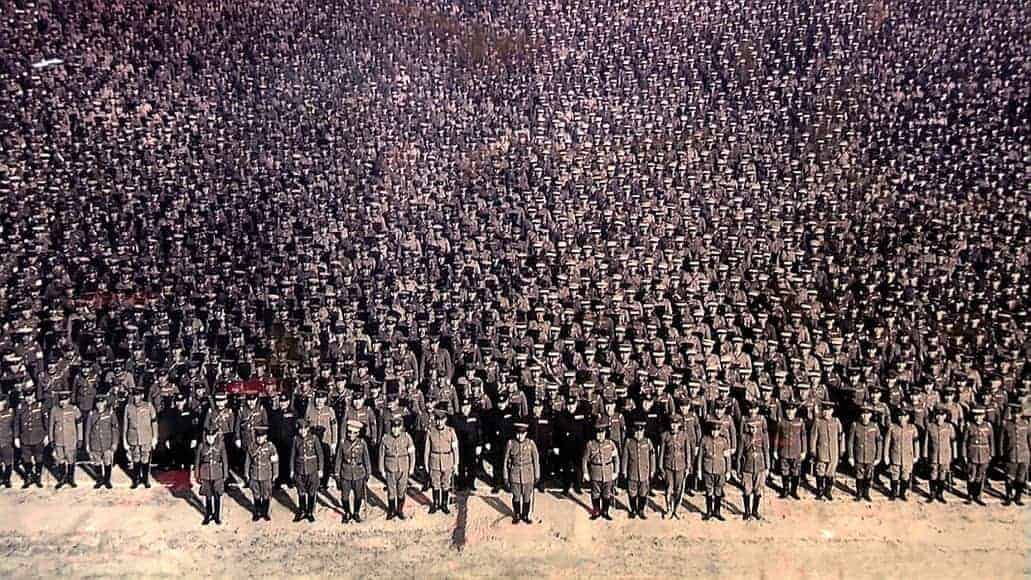

Probably the most impressive part is the third, titled “Hoichi the Earless”, about a young blind monk-musician, who plays the biwa. His specialty is singing the chant of The Tale of the Heike about the Battle of Dan-no-ura fought between the Taira and Minamoto clans during the last phase of the Genpei War. The segment begins with a kind of Japanese theatre/opera, were paintings of the aforementioned wars are juxtaposed with live action by actors portraying the events, although without speaking, with the story coming from a narrator, occasionally accompanied by music. After this part, the segment becomes more “normal”, as we watch Hoichi being forced to perform for a band of ghosts.

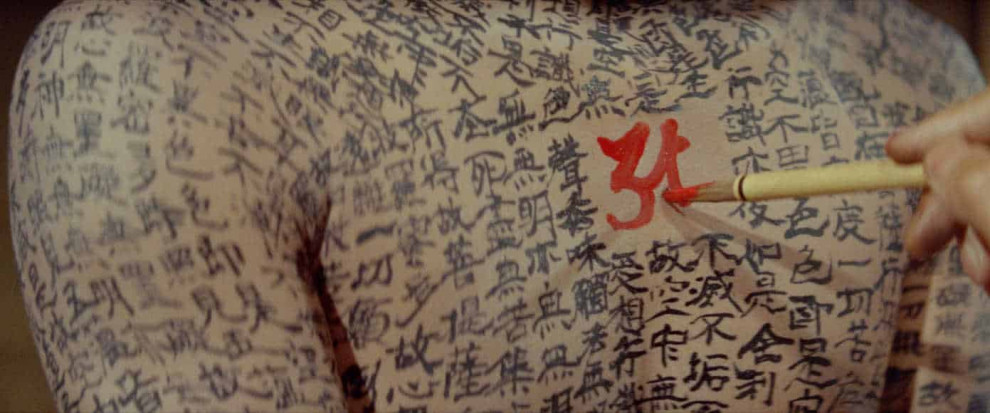

This part focuses on the blights of carelessness and perhaps pride , with the protagonist, once more, suffering an awful fate, despite the efforts of his fellow monks. The ending is quite impactful in its violence, while the scene where the monks paint Hoichi's whole body is one of the most impressive in the film. Katsuo Nakamura is excellent here in the protagonist role.

The last part, “In a Cup of Tea” is probably the tamest, as it focuses on a ghost story told by a writer, about Sekitai, an attendant of Lord Nakagawa Sadono. At one point, Sekinai sees the face of an unknown man in a cup of water, and despite his efforts to get rid of it, every time he fills it the same man reappears. Furthermore, a bit later the person whose face was shown in the cup appears in the flesh, initiating a number of unfortunate events for Sekitai. The ending returns to the story of the writer, which concludes in rather whimsical fashion.

Evidently, the context is not of the highest value, with the stories being, in essence, fairy-tales with some didactic elements here and there. However, the reason “Kwaidan” is considered a masterpiece is for Yoshio Miyajima's impervious cinematography, but most of all, for its hand-painted sets, which were built in an airplane hangar, the only space that could contain their vastness. This artistry becomes evident from the first frame, but the more one watches the movie, the more layers are revealed, in a true visual extravaganza. The training scenes in the first part, the passing of seasons and particularly the snowed forest in the second, the presentation of war in the third and the fighting in the fourth are true wonders to look at, and are bound to stay in the mind of the viewer. The 2K restoration helps immensely in their presentation, highlighting their artistry in the best fashion.

“Kwaidan” is a film that truly deserves to be watched, not just seen, as a genuine visual poem and a true classic of world cinema.