Absence haunts the streets of Masaya Takahashi's Maebashi City: as absent as the rains are during the apex of summer is the nurturing essence of humanity. Parched of comfort and joy, the inhabitants, so jaded by circumstance and experience, find their ability to thrive has diminished beyond comprehension; instead, fear from just a knock on the door flourishes where little else can. Yet there exists a responsibility to keep up appearances so those whose innocence remains intact are not doomed to follow those same footsteps. Based on Mitsuru Kawabayashi's 1990 novel of the same name, Takahashi's ‘Dry Spell' explores the insurmountable hardships of growing older amidst the harsh realities of a world plundering itself of human decency. Thirty years after the novel's publication, its examination of poverty, especially amongst children, remains as true and as poignant as ever.

Dry Spell is screening at Camera Japan

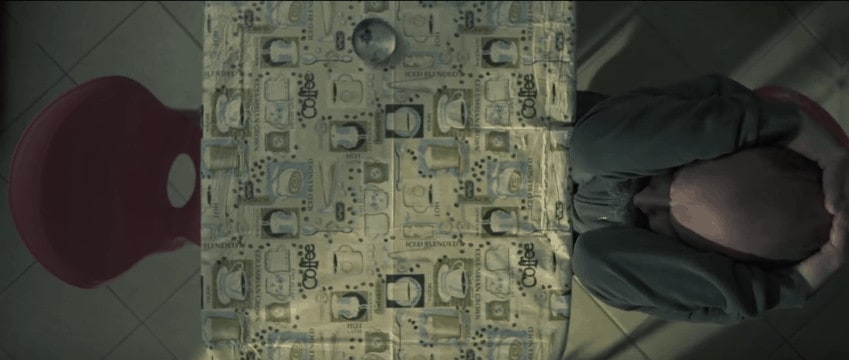

Bearing the brunt of a heatwave with zero percent chance of rain, Maeboshi faces a public water shortage. Pools are closed, empty, and locked; one by one the public faucets are being switched off; and even the water department's vehicles remain dirtied to set an example. Tasked with shutting off the water supply to those behind on their bills, Shunsaku Iwakiri (Toma Ikuta) commits to his harsh endeavour with bureaucratic civility unmoved by the clients' pleas for more time – only when he routinely stops at the single-parent Koide household he becomes lenient to their plight. But when the mother abandons her two young daughters Keiko and Kumiko (Yamazaki Nanami and Yuzuho) for a potential relationship, their already desperate situation deteriorates further and the two girls are left to fend for themselves. When Iwakiri and his colleague Takuji Kida (Hayato Isomura) return to fulfill their obligation, they carry out one more act of generosity before they parch the house of water.

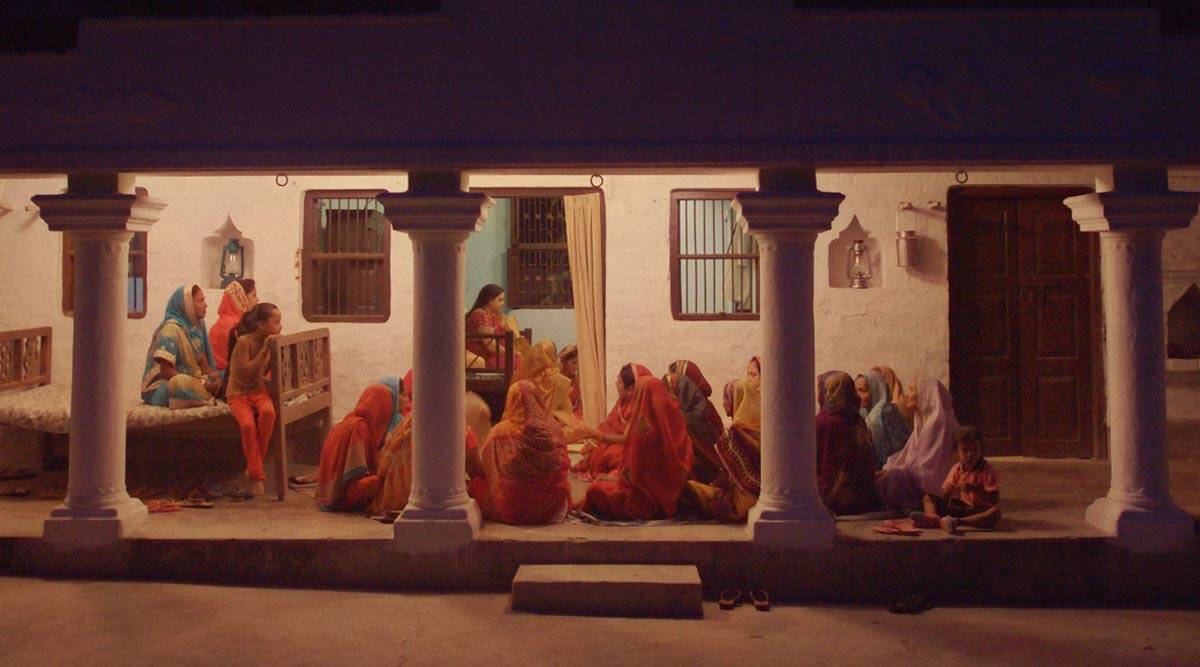

It isn't too long before the sisters are forced into stealing from local convenience stores in order to ensure their meager survival. Meanwhile, Iwakiri is wrestling not only with his conscience but with his wife's separation and taking their child with her in the process. Though Takayashi spends considerable time humanising an uncaring practice and reinforcing its absolute human impact, ‘Dry Spell' shines within its subtleties, carefully revealing the internal dilemmas and responsibilities absenteeism has long burdened upon Japanese society. Taking its toll on Keiko, her dual role as both mother and sister to Kumiko long before their abandonment has all but eroded her childhood; she represses her vulnerability from all those around her in as much the same way as the adults with whom she crosses. Through her dedication to her sister and Iwakiri's resolve to reclaim his humanity and his ideals – brought to a head in an underwhelmingly saccharine climax – ‘Dry Spell' revels in showing there is more at stake than just water.

Sitting at polar opposites to each other Keiko and Iwakiri have more in common than they would care to acknowledge: their lived experiences have left them in a state of self-disassociation and intrinsically untrusting of those whose innocence has since been corrupted in some form. Here, both Ikuta and Nanami expose their inner truths through their eyes, body language, and facial cues in lieu of dialogue; their nuanced performances not only deter the film from sentimental indulgence but also from any reliance on the score to drive its emotional weight. Perfectly countering Yuzuho and Isomura's youthful naivety the pair unflinchingly don their masks, carrying their burden with but a glance or a pupil dilation to suggest otherwise. Their understated performances feel all too real and admirably underscore the plight of Kawabayashi's source material.

Across its runtime ‘Dry Spell' peels back and exposes its characters' innermost sanctums through thoughtful pacing and editing. As the heat and water situations deteriorate, so too does Keiko and Iwakiri's ability to thrive in this unforgiving landscape; piece by piece Takahashi strips back his cast's vulnerabilities and forces them to the fore in minute details. Framing these against a scorched and parched backdrop is Ryutaro Hakamada, increasingly isolating the principal cast from the world around them as they plumb the depths for both water and their own survival. So favourable is the technically minimalist approach here the implications of the water department's actions are allowed to take centre stage, slowly devolving until both Iwakiri and Keiko cross the point of no return.

Far from reaching the intensity of Koreeda's ‘Nobody Knows' Takahashi's film remains a sobering experience driven by tempered forces and quietened voices vying to be heard. Mirroring Gunma Prefecture's heatwave of 2022, and emphasizing with sincerity the dilemmas of Japan's hochigo (left-alone children) ‘Dry Spell' lingers in a cruel and very real domain, one which may feel too close to home for many, at a time when economic uncertainty is all that is certain. And yet, despite its harrowing cynicism, the film refuses to preach and overwhelm; instead, it establishes a grounded connection to see the world through its characters' eyes and nothing more. It doesn't go far enough to deal a provocative hand and by its finale, undoes most of its own work for the sake of satisfaction, but the memories it imprints will be hard to shake off.