Can you tell us some of the main characteristics of Tibetan language?

This is shown very well in Pema Tseden and Sonthar Gyal's films, where one can sometimes hear 2 or 3 languages or dialects. Tibetan language is not unified: it is a family of languages, like Roman languages, and not a language per se, a bit like Chinese, which is divided into Mandarin, Shanghaiese, Cantonese, etc. In the same way, Tibetan is split into three main languages, there is Tibetan from Central Tibet (Lhasa, Shigatse, etc.), Tibetan from Amdo and Tibetan from Kham. Each of these languages are divided into dialects, tens of them, sometimes with little mutual understanding. Tibetans have been struggling to find a Lingua Franca, but the Chinese government is very reluctant to support that move, united Tibetans is not a nice perspective for them, so they keep it that way, even though they did the exact opposite thing with Putonghua. So, sometimes, Tibetans do not understand each other. For example in “Balloon”, the main actress, Sonam Wangmo is from Lhasa. It means she cannot speak and cannot understand what her character is supposed to say in the movie. She had to learn her lines by heart, because she had to speak the local dialect. But now with social media like WeChat, many Tibetans can listen to other dialects and mutual understanding seems to be on the increase.

Are these languages and dialects disappearing though, due to the spread of Chinese language, as we see in Pema Tseden and Sonthar Gyal's films?

That is a huge concern. Tibetan language is in danger now because of the school system and TV. As we see in “Lhamo and Skalbe”, the little kid is watching cartoons in Chinese. This is very dangerous for the survival of Tibetan because these programs are very appealing and super modern. Developing a competence in Chinese is desirable of course, but most Tibetans complain that it is often done at the cost of Tibetan. So, Tibetans are full of anguish regarding the future of their language.

I refer readers to the newly published and excellent report by Human Rights Watch on Tibetan language in Chinese education https://www.hrw.org/news/2020/03/05/china-tibetan-children-denied-mother-tongue-classes

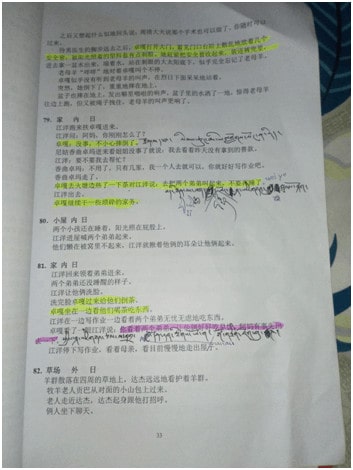

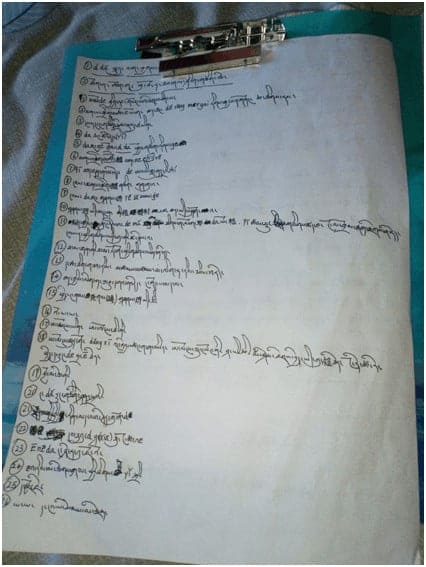

Another thing about language: when they make films, Tibetan filmmakers have to submit the script to NRTA (National Radio and Television Administration) and they have to write it in Chinese, so sometimes, there is no script in Tibetan. For example, in “Wangdrak's Rain Boots”, when the kids were trying to learn their lines, the text was in Chinese, and they had to speak in Tibetan something they learned by heart in Chinese. I saw it with my own eyes as I was lucky to spend a few days during the shooting there.

This is a very good example of how difficult it is to use Tibetan in everyday or professional life in China. Apart from the monasteries, maybe only Tibetan hospitals and some Tibetan schools now use Tibetan written material, but wherever you go, whatever you do, Tibetan language is sidelined, which is something Tibetans strongly resent. They have launched, in reaction, groups to promote “pure Tibetan language”, educational posters and materials that provide modern Tibetan terminology, so as to counter the tendency to use Chinese terms (for numbers, for everyday modern technology, etc.). That movement was very popular in some parts of Tibet: while it was once customary to hear Tibetan conversations peppered with Chinese, now many Tibetans have gotten used to eliminate Chinese words and speak purely Tibetan language. You saw in “The Valley of Heroes” a bunch of students who go to areas where Tibetan language is disappearing, so as to promote the language and educate people, but this practice has recently been forbidden by the Chinese authorities.

How difficult is translating Tibetan language?

As difficult as Chinese, Japanese, etc. One big difference though is that language manuals and teaching methods are much more recent and less advanced than for other Asian languages, and also that most translators so far have only focused on the prestigious, classical, literary Tibetan, not on spoken, vernacular, contemporary Tibetan.

How did you come to know these Tibetan filmmakers though?

I always loved movies so it is a nice coincidence that the people I knew ended up becoming filmmakers. I met Pema Tseden a bit before he became a filmmaker, so before 2004. I think it was 2002. He was then studying in Beijing and he was writing short stories at the time, so I wanted to meet him because I was studying for my PhD in Contemporary Tibetan Literature, and I wanted to meet all these people who wrote in Tibetan, who wrote short stories. So, I met Pema Tseden in Xining and at one point, he told me that his dream was to go to Cannes one day and present his films, and I was really surprised. Of course, he was not known then yet, and he still had to prove himself. It is actually a miracle that he has managed to reach this far with such a limited film cultural environment, and limited financial means. Then, in 2006, we were lucky to have Pema Tseden's first film, “The Silent Holy Stones” shown in Paris, as part of a delegation of Chinese filmmakers. I went to see it and I met Pema Tseden again at the time. Xu Feng, who speaks French and Chinese and teaches cinema at the Beijing Film Academy, has been from the start very instrumental in establishing connections between these Tibetan filmmakers and French film festivals, just as I have been instrumental regarding the Tibet connection, through Tibetan language, subtitling etc.

Actually, my first friend in the business was Sangye Gyatso, who was Pema Tseden's first producer. He is also a great poet, whose poetry I have translated, and I had met him before. But suddenly he became a producer and has kept supporting Pema Tseden since them. “The Sacred Arrow” is shot in his home valley.

Can you tell us a bit about the experiences you had in Tibetan movie sets?

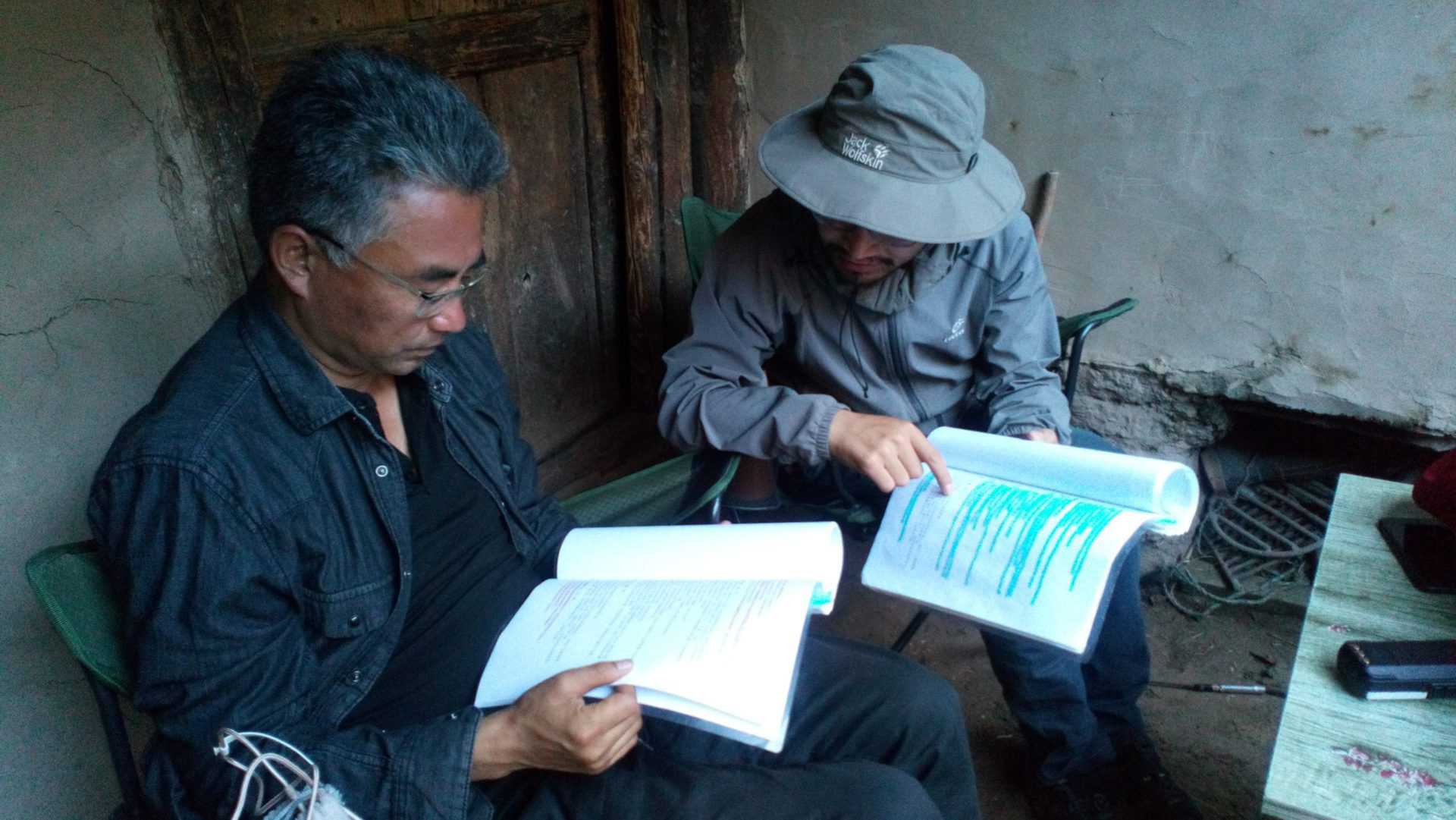

I have been on set four times so far. It is very interesting because you see how the connections are being made; how the relations, the friends connect to each other; it is a gradual team building. The atmosphere is very genuine and friendly. There is a core of about 20 young men who have been working with each other for some time, and actually work like crazy and are improving, in the midst of very complicated material situations. Because when you are shooting in Tibet, it is always in a rural environment, sometimes there is no electricity, sometimes there no running water etc. For example in “Wangdrak's Rain Boots”, we slept in a school, and I took a picture of Pema Tseden, who shared a room with director Lhapal Gyal.

Its only luxury was that there were only two of them in the room, instead of ten in other rooms. Of course, there was no bathroom, the toilets were outside etc, no kind of luxury there. I think, however, that these circumstances actually bring people together. Pema Tseden is famous among his crew for insisting upon not being treated in a special way, apart from being allotted a room for himself, or with a director when he visits another film set, because every evening he has to prepare for the day after's scene and meet many people to give instructions, as well as to work with the editor.

Have you met Jinpa the actor? Is he a rock star type, like he is in the movies?

Yes, he is exactly as he is in the movies. He is really nice though, he is actually a herder, you see him handling sheep in “Balloon” and this is exactly what he did before, and he has actually opened a kind of cultural cinema cafe in the pastures, in Machu, where he was born, and he promotes film there (laughter). He also writes poetry, and he initially became famous through his poems about sex, which were quite open. A lot of people found them very interesting. He also published some famous pictures of himself coming out of the water naked, tilting his hair backwards. This contributed to his fame. In Tibetan culture, you never think of yourself as very important, therefore, I do not think anyone has the mentality of the star, it is just impossible, it would be considered an unethical and even laughable behaviour. Therefore, Jinpa helps around, plays the flute sometimes when he has nothing to do, and he reads books and he laughs etc, just like everyone else.

So, you like him.

Yes, I like all of them, they are both very cool and very committed. This is what I like the most about them, there is this common idea that “we are creating an oeuvre, we are part of this historic moment of creating Tibetan films, so let's do our best”.

How did Pema Tseden's books came to be translated to French first and then English?

In France, contrary to what happens in the English-speaking world, some publishers love books more than money. To answer your question though, I met Pema Tseden in New York in 2011. Brigitte Duzan, an expert in Chinese cinema who does subtitles, translates Chinese literature and has a very interesting French-language blog on Chinese literature and movies, loves Pema Tseden's cinema and badly wanted to translate some of his short stories. I approached Pema Tseden in 2011 and I told him, from both of us, that we would like to publish some of his works, so I asked him what he would recommend. Pema Tseden is sweet and nice but he can also be bossy so he gave specific instructions for what I should translate from Tibetan and what Brigitte should translate from Chinese. We did what he asked. I sent our translation, seven short stories altogether, including “Tharlo”, to the leading French publisher for Asian literature, Philippe Picqiuer. The next day literally, he rang me up and told me he wanted to publish the material. This was wonderful, we did not have to beg the publisher or try to convince him. The resulting book, “Neige” (2013), was quite successful actually, and has now been published in a pocket version also, a soft-cover one.

Buy This Title

As far as I know, it has been more complicated for “Enticement”, a collection of Pema Tseden's short stories translated into English, because the American publishers' marketing style is more quantity-centered, so they are more difficult to convince. Therefore, it was harder for Patricia Schiaffini and Michael Monhart to convince the publisher that it was sellable; not only good but also sellable. But they did manage to convince him and the book has now been out for 1,5 years. Brigitte Duzan is now preparing another volume of translation of Pema Tseden's short stories from Chinese into French, for the same French publisher. It will include the short story “I killed a sheep”, which partly inspired the film “Jinpa”. The book cover will show the two Jinpas in the lorry.

In general, how would you describe Tibetan literature?

Actually, for many years, writing has been the only easy way to assess yourself culturally as a Tibetan, because no one writes in the Tibetan language but Tibetans. It is cheap, you just need a pen and a paper and you write stories or poems. Tibetans have a long tradition of epic and beautifully crafted literature. Tibetan is in fact a very old written culture. However, Tibetans did not write realistic stories until the 1980s, it was always folk tales and epic tales, which are beautiful in terms of literature and the construction is exceptional, but not realistic. They were written in a Buddhist environment, where people wrote for enlightenment, not for fun. But with the new generations, Cultural Revolution and new schooling, the Chinese government really promoted the invention of a “modern”, realistic Tibetan literature in the beginning of the 80s. You had to be modern, and to write short stories and novels. The government heavily subsidized literary magazines and publishing houses (there are no private publishing houses in Tibet, everything that is published in Tibetan has to pass through the state publishing houses, which is not the case for Chinese language works). So, Tibetans were able to write and publish books that way, and they embarked in realistic writing very fast, naturalistic, regionalistic, even science fiction, nurtured both by their own literary culture and by world literature, which they could read in Chinese, not in Tibetan. For example, when I met Jinpa, he was reading “1984” in Chinese (note that it has been translated too in 2 different Tibetan versions). I must say the Chinese government really nurtured this literally scene of Tibet, and Tibetans easily embraced it because they hold aesthetic writing in very high esteem.

So, you have this young generation who was trying to express itself, but they were not monks or clerics, who were almost the only ones who wrote literature before. Literature now has become one of the main ways of discussing social problems, mainly in the guise of fiction or poetry. I call this the “Boomerang Effect”. It is very interesting because you get these subtle messages, the anxiety about the future of Tibetan culture through literature, and now through cinema. Pema Tseden once said that he started writing because he could not shoot movies, it was an alternative. Now, 30 years since the first Tibetan language realistic novel was written, about 30 Tibetan novels have been published, as well as hundreds of short stories, and thousands of poetry. Some of them are really good, there are possibly 10 to 15 really good writers who deserve to be known outside Tibet.

Is there actually a movie industry in Tibet though? Screening rooms for example?

Zero movie industry yet. There are some screening rooms, but are mostly derelict, heritage of socialist China who would show North Korean movies. Now, however, cinema is coming back again in big cities, for example the First Film Festival in Xining, which is pretty close to Amdo, screens films in brand new movie houses. Lhasa also has some cinemas. But in the countryside, you watch films on your phone or computer. But Tibetan films are shown in theater halls on in urban Han China, where Pema Tseden and Sonthar Gyal have become kind of stars and have real success.

One more thing I would like to say is that recently, Sonthar Gyal has set up a kind of base, Garuda Media, half a movie studio and half his office, where he devises his films and also shoots commercials. It is in the same area that “Lhamo and Skalbe” was shot, in Qinghai province. The local government funded part of it, as a local startup. It is a very interesting round building, where the light comes from the top, which he actually designed himself. He wants to develop something locally because it is always a big cost to bring filming equipment from other places and also he wants to create an archive and to have a place where he can teach cinema, show films, etc.

Do Tibetan filmmakers face censorship from China?

Yes, as much as other filmmakers, even more sometimes. In China, film scenarios must be submitted (in Chinese language only) to censorship, but when one makes a film involving “ethnic minorities”, there is another bureau that comes in, the Ethnic Affairs Bureau, who has to give their opinion also. And when the film deals with Buddhism, or any kind of religion actually, then you also have the Religious Affairs Bureau, who also have their say. Pema Tseden's original plan was to make a sequel for his first film, “The Silent Holy Stones”, by showing the main protagonist, a young monk, on a pilgrimage to Lhasa with his master. But he was not granted permission – too religious. Another example: in “The Search”, the film director in the movie casts a group of young dancers and asks them if they can read Tibetan. In the original script, the answer was negative, but this was not allowed in the film, because it would have indicated flaws in the Tibetan-language education system, something that Chinese authorities are not too eager to publicize.