From this perspective, after being quarantined over two months, the notion of being able to reset one’s mind to the state of “zero” sounds not only tempting, but essential for returning to a different kind of reality, psychologically undamaged. The scientific formula for letting go of personal fears caused by whatever trauma or mental issues offered by the now retired Japanese psychiatrist Masatomo Yamamoto, sounds like a wizardry coming straight out of Hogwarts, but it’s only fair to recognize that it won’t work by simply listening to the old man talking to his patients. This is the core narrative of the documentary “Zero” by Kazuhiro Soda, a slowly-paced but nevertheless exciting insight into a complex, fascinating world of elevated psychotherapy developed by a man who defied many socially-imposed rules, securing himself a very special place in the history of the soul-healing science.

The Japanese filmmaker Kazuhiro Soda is returning to his subject from the black & white feature “Mental” (2008), this time with a slightly different, more intimate approach to the man who created the foundation for the community-based mental health care in Okayama, pushing the envelope not only in the treatment of mental patients, but also in destigmatizing the image of the “weak” and the “unfit” in the eyes of the Japanese society.

Dr. Yamamoto is about to retire, and in his farewell speech addressing the colleagues and the former patients, he is talking about the biggest problem the mental patients are facing – lack of respect. This is also the focus of the film; a very special bound the old psychiatrist had managed to establish with his patients, who are strongly attached to his respectful, attentive way of dealing with their problems.

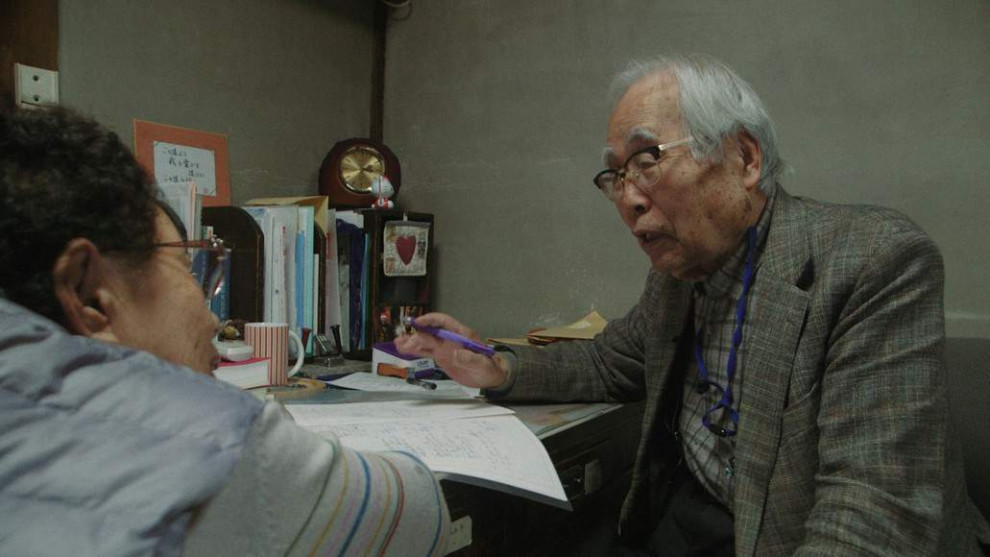

The old footage and the new takes blend in an observational study of patients’ progress over the years, with the camera focused on little, significant details such as facial expressions, hand movements, nervous ticks. Always alert, Kazuhiro Soda doesn’t let the crucial moments of interaction between the doctor and his patients go unnoticed – the mutual trust built on solid ground and years of therapy takes the best and the worst out of them in the time of insecurity, with the old man retiring, not really ready to let go, but on the other hand heavily marked by his age and the rapid deterioration of his physical capabilities. He has to face his own mortality, but that is the thing that seems to bother him less than letting his patients down.

Acting not only as the director, but also as the cinematographer, as in all of his films, Soda can easily bridge the gap between his early takes on Dr. Yamamoto and the now. The shift of focus from doctor’s professional to personal life happens gradually, changing drastically towards the second half of the film, following his heavy decision to call it quits. The camera gets steadier, embracing the new environment and circumstances. It is the lesson in documenting reality of the finest art, non-interventional, childishly curious, and warm-hearted.

Somewhere around the film’s second half, a 82-year-old Yoshiko – Yamamoto’s wife, finally gets her voice. In “Mental” seen only as a cheerful house help and the partner, she steps into the focus as a loyal, patient companion, who had to endure all the hardships her husband mostly advised his patients against. The sudden shift of interest from her husband to her, steers the film into a very interesting direction. This decision can be read as the subtle critique of gender roles, without deconstructing the image of the film’s titular character. During the couple’s visit to Yoshiko’s long-time friend that she used to perform the tea ceremonies together, her love of kabuki and classical music, the unpleasant details from the couple’s life appear, with an interesting confession by the doctor himself, that he might not be perfect after all.

Technically seen, Kazuhiro Soda knows exactly what he’s doing. His presence is left noticed by interfering with the film’s flow – whether through the small-talk to teenagers on the street who think they are being filmed for a popular TV show, or by letting his voice dominate the q&a in the second half of the film, digging for the personal information about Dr. Yamamoto.