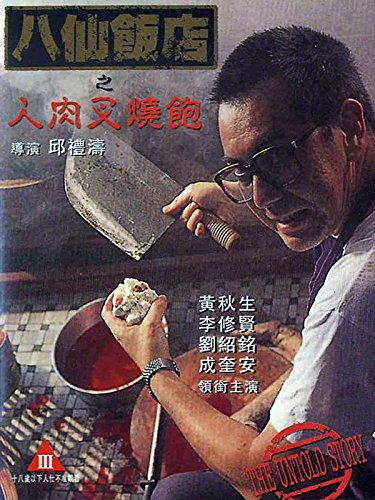

Hong Kong film releases are classified into three main categories: Category I, II (which is further divided into two) and III. Category III (usually called by its abridged name Cat III) is the equivalent of something like NC-17 in America, where people under 18 are strictly not allowed due to the depiction of nudity, sex or extreme violence. Of the many, many Cat III works released, probably the most infamous is Herman Yau's “The Untold Story” from 1993. Despite its restrictive rating, it went on to be a hit at the box office and earned lead actor Anthony Wong a Best Actor nomination and his first win at the Hong Kong Film Awards, before going on its way to become a notorious cult classic.

Watch This Title

The story opens in Hong Kong, 1978, as we see an argument between two gamblers over a debt, with one violently killing the other by bashing his head against a wall and setting the body and the house on fire, immediately introducing us to the mahjong addiction and violent streak of Wong Chi-hang. Cue eight years later, and police in Macau are called to the beach when a family discovers a bagful of dismembered body parts. Investigations lead them to the Eight Immortals Restaurant, now run by Wong Chi-hang. The restaurant, apparently, can't seem to keep a hold on its staff for a long period of time and its barbecued pork buns are selling like hot cake for some reason. How did Wong Chi-hang end up in Macau and in the ownership of the Eight Immortals Restaurant? Where has its original owner Cheng Lam and his family disappeared to? And what exactly is the secret ingredient in those pork buns?

Director Herman Yau's “The Untold Story” is outrageous, disgusting, vile, gruesome, demented and repulsive at times, but a lot of that is due to the fact that the real-life events and person that it is based on are all of that, and more. Yau, no stranger to Cat III filmmaking, presents these most horrifying real-life events in the most unflinching manner, his camera rarely shying away from the gruesome details of the crimes of Wong Chi-hang, demanding a strong stomach from its viewers and fully earning the Cat III classification.

While some may view this as sensationalism or exploitation, the fact that these events occurred, particularly the crimes that Wong confesses to in the climax, just about stops it from being pure exploitation. To enhance the shock value, Yau makes use of practical effects to convincing results. The scene in the jail as Won Chi-hang tries to take his own life is a great example of the same. Cho Wai-kee's close-up camera work combines with the practical effects to create wince-inducing imagery.

Through the cops and their ridiculously incompetent investigation, Yau presents some satire of the police procedures in Hong Kong and Macau at the time, and herein lies the present work's biggest and only flaw. This portion is presented in slapstick format, which just doesn't sit well with the otherwise dark tone. While the black comedy hits its mark almost every time, the tonal shifts between the goofball policing and Wong Chi-hang's shocking acts are conflictingly awkward, which is particularly troublesome since Yau wants to ultimately make a strong statement on police brutality here.

The sudden transformation from bumbling idiots to Guantanamo-style torturers in the final act also doesn't sit well with the characters that we've seen until that point, but it does pose an interesting question if we're witnessing the “untold story” of the heinous crimes or of the police brutality portrayed. Only Officer Lee, played by Danny Lee (who also acts as producer here), comes out unscathed. That's not to say that any of the supporting actors are at fault. Danny Lee plays his part well as playboy Officer Lee and Emily Kwan, Eric Kei, King Kong Lam and Parkman Wong who form the investing police team, all share good chemistry.

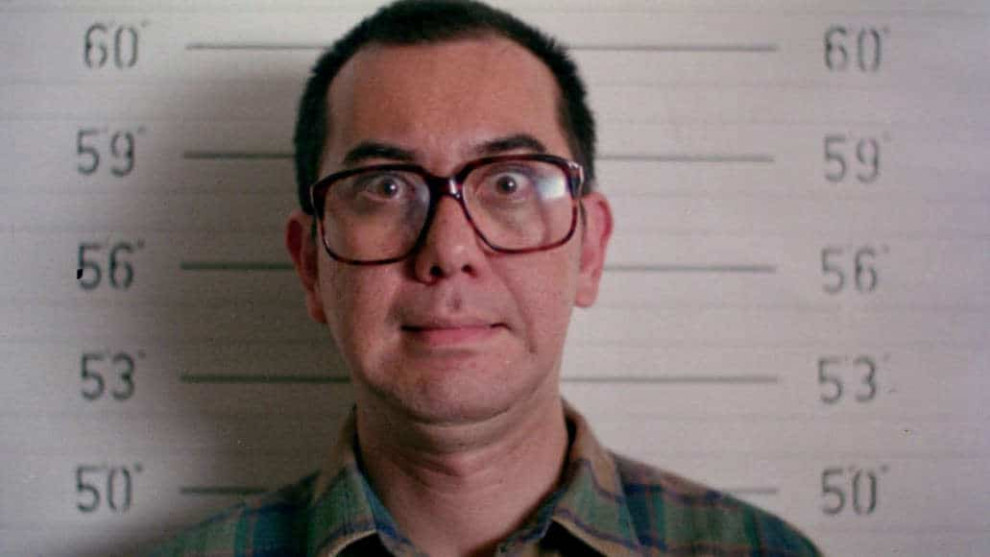

It's a good job that Yau has an actor of Anthony Wong's calibre along for the journey, because he is just mesmerising here. Letting go of all inhibitions, he immerses himself completely into portraying the twisted mind of this monster Wong, a breakout role for the actor and one of the finest depictions of a serial killer put on screen. It is to both director Yau and Wong's credit that they manage to gather sympathy from the audience even for such an outright despicable character at times, even if this sympathy often see-saws with repulsion.

Take the scenes in the jail, for example. We have already seen Wong Chi-hang brutally murder three people and rape one woman in the most unimaginable way and do unspeakable things with the bodies, but you still feel for him when you see his treatment at the hands of the police and the other inmates. Just as we start to feel too sorry for him though, the film cuts to Wong Chi-hang's original crimes when he first arrived to Macau, with Anthony Wong's crazed, psychotic eyed performance snatching away even the tiniest shred of sympathy you may have garnered for the character.

“The Untold Story” spawned two sequels that never came close to the sheer horror of the first film. To date, it stands a landmark work of not only Category III filmmaking but also of works based on real-life characters incidents. Watch it on an empty stomach and be prepared to never look at barbecued pork buns or indeed chopsticks in the same way ever again.