“Non-Fiction Diary” is Jung Yoon-suk's second documentary and had numerous appearances at several film festivals. Moreover, the it won several Awards, namely the Netpac (Network for the Promotion of Asian Cinema) Award at Berlin and the Mecenat Award at Busan.

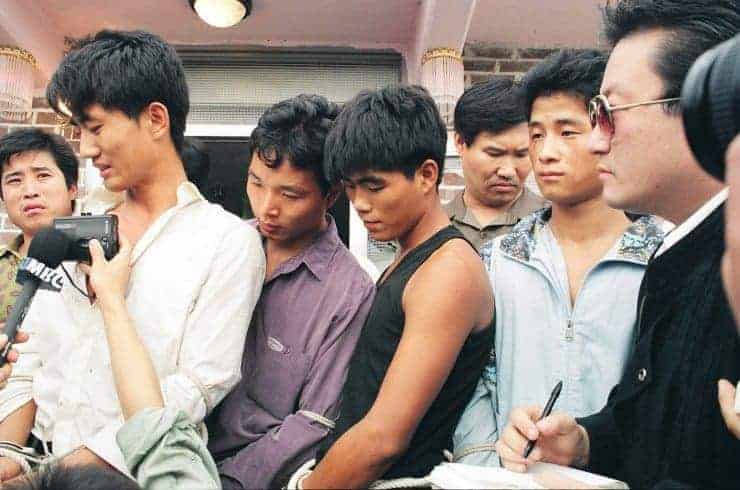

The main axis and backbone of Jung Yoon-suk's “Non-Fiction Diary” is an event that occurred in 1994 and shocked the Korean nation. This event is the surface and capture of the Jijon Clan, which consisted of six serial killers who kidnapped, raped, ate and burned five people and even forced one of the women hostages to participate in the killing of her boyfriend. After Jijon Clan's arrest, which was possible when the aforementioned victim managed to break free after gaining their trust, the serial killers claimed, without showing a single drop of regret, that they committed all the hideous crimes, in order to punish the wealthy. However, their victims were ordinary people and not wealthy, by any means. Jijon Clan's members were sentenced to death and executed in 1995.

The documentary has the form of interviews of the people indirectly or directly involved with the case. Some of these testimonies are from the former detectives of Seocho Police station's violent crime Unit, from a human rights lawyer and from a former nun chaplain. One clever approach of the events' presentation by Jung Yoon-su is the combination of the interviews of the two former detectives of the Seocho Police station, which are presented successively. In that fashion, additional details regarding the Jijon Clan are presented.

Jung Yoon-suk takes all the major elements of the case and underlines other important events of the Korean history during the 90s, that have something in common, either in terms of the people involved, like the former police detectives, or having the same hidden source. These events are the collapse of the Seongsu Bridge in 1994 and the collapse of the Sampoong department store in 1995 that share the intentions of the people involved. Both the executives involved in the creation of the bridge and the department store, and the members of the gang wanted to earn more money (the gang in order to give them to their leader). The executives wanted to have profits as fast as possible, and this cost human lives. This cost leads us to the second common fact, which is no other than the murdering of people. In the case of the two collapses, the unintentional loss of life due to the bali bali Korean culture (to do something as quickly as possible) and in the case of the Jijon clan, is the intentional removal of human life. Both are murders, even though the scale is different. Moreover, an additional message is included: capitalism, directly and indirectly, leads to the death of people.

As was already mentioned, the members of the Jijon Clan were sentenced to death, and the director grasps the opportunity to stress the theme of the death penalty. He presents the story of executions in South Korea, starting with the spies from the North, that comprised the majority of these sentences, and then asks the interviewers regarding their opinion on the death penalty.

Moreover, there are subjects that the documentary emphasizes. One of them is the establishment of laws in order to avoid deaths due to human negligence and not following proper safety procedures, an outcome deriving from the corporate thirst for fast profits. Another is the establishment of the Center of Filial Piety, as an effort of the government to restore morals resulting from the Jijon Clan case.

The documentary has some important strengths but limitations as well. Among the strengths, in terms of directing, is the screen's splitting in two unequal frames at the beginning of the documentary, which present the important events that the documentary focuses on. Other strengths are the background music and the beautiful scenes of the Korean countryside's roads. Furthermore, Jung Yoon-suk's editing, in general, is very good and facilitates the differentiation of several themes, except for a very few occasions. On the other hand, one important drawback is the documentary's final segment with the parade of the various presidents of South Korea and their punishments, as this demands from the viewer to be familiar with the Korean history.

On a final note, it is worth mentioning that the name that Jijon Clan bestowed themselves is “Maskan”. As the documentary says that means “ambition” in Greek, but I can't think of a word in Greek that sounds similar to “Maskan”. Nevertheless, “Non-Fiction Diary” is a worth watching documentary, which, surprisingly, ends on a very positive note.