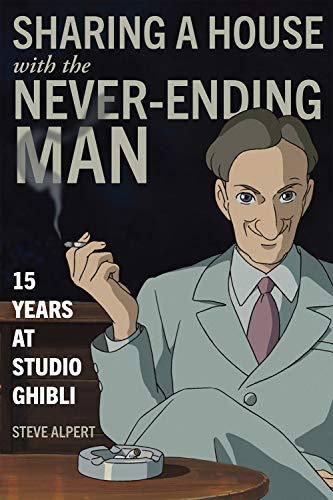

Titled after Kaku Arakawa's NHK documentary about the Japanese anime visionary Hayao Miyazaki “Never-Ending Man”, Steve Alpert's business memoir “Sharing a House with the Never-Ending Man” tells the story of the famed anime studio from a different perspective, that of business.

Buy This Title

In the middle of the nineties, the then-Disney employee Steve Alpert was scouted by Toshio Suzuki from Studio Ghibli to head the newly opened international division of the studio's parent company, the conglomerate Tokuma Shoten. For the next fifteen years, he worked for the company, helping it grow and get numerous international deals. Together with that, he was also a member of the board of directors of the studio and the only non-Japanese at that, in the entire company. As such, Alpert had a unique position within the company. As a high-level insider, he had direct contact both with the boss of Tokuma Shoten, the extravagant old-timer Yasuyoshi Tokuma, the creative geniuses behind Studio Ghibli's films, and executives from other companies such as Disney, Pixar, and Miramax. However, he was also an outsider of sorts, due to being a gaijin (a non-Japanese). His unique position within the world of Japanese animation, coupled with him being present during some of the most important moments of the studio's history ,such as the move towards digital animation and the expansion to American and European markets, gives Alpert the unique opportunity to contribute to our knowledge about Ghibli. And he does that very effectively in his memoir “Sharing a House with the Never-Ending Man.”

Through Alpert, we learn about what life in a Japanese company in the 90s was like, with all of its quirks such as unnecessary speeches, complex hierarchy, sleeping during meetings, shady business, and smoking. A whole lot of smoking. Through such interesting and quirky stories, such as Tokuma's boss buying his executive vanilla ice cream and watching them eat it or Suzuki's decked-out car in which he basically lives, we get a fuller image of the people behind the films and their never-ending work towards perfection. Interestingly, though, there is nothing said about Isao Takahata which is very strange. Of course, few of the stories tell anything that hasn't been already said in the manifold books and movies about Hayao Miyazaki & Co. but they nevertheless work within the context of “Sharing a House with the Never-Ending Man.”

Yet, the book does something much more than recount strange stories about being a non-Japanese in a Japanese company. It also explores the business side of Japanese animation and specifically, its international distribution. Alpert does this very well by choosing to focus only on a small part of his stint in Ghibli, namely the years between the creation and distribution of “Princess Mononoke” and “Spirited Away.” He pays more attention to the first movie as it is around that time when Studio Ghibli signed a contract with Disney (a deal on which Alpert spends a considerable amount of time and space) and the first major release of a Ghibli film for the American audiences. Concerning the latter, he mostly speaks about the difficult award season and Miyazaki's refusal to attend ceremonies, including the Oscars.

The distribution of “Princess Mononoke” in the US, which was supposed to be done by Disney but was later relegated to Harvey Weinstein's Miramax, gives Alpert the opportunity to speak about the process of localization of Japanese films for the international (read American) markets. The process is very complicated, especially in the case of complex and ambiguous films like “Princess Mononoke” which Miramax head honcho Weinstein believed would not earn much money if not changed. So, he tried to alter it to fit the simpler American expectations, in the meantime dumbing down Miyazaki's vision. He did this not through discussions but by going behind Ghibli's backs, lying, threatening and throwing a tantrum or two.

With such a depiction, Alpert paints pretty obvious villains in the face of Miramax and possibly Disney who disregarded everything and were ready to do anything just to make the movie sell tickets. For example, they hired the sci-fi author Neil Gaiman to write the English-language script for the movie just to completely ignore his faithfulness to the original script, added a ton of unnecessary music, sound effects, and exposition and went against the contract on a thousand occasions. Such a depiction, of course, makes sense as the book presents a very subjective perspective about this time in the history of the Ghibli and is written by a Ghibli executive. Still, the book would have benefited from a somewhat more nuanced depiction of the parties involved.

This brings us to what is possibly the biggest weakness of “Sharing a House with the Never-Ending Man”, its writing quality. Yes, the story is entertaining and at times difficult to put down, but at the same time, it often reads more like a cheap pulp or an 80s story about “the Orient” that exoticizes Japanese people for better sales. There is just too much bombast in some of the paragraphs and way too many generalizations and exoticizations of Japanese corporate culture, at least for this reviewer's liking. This ends up slightly hurting the believability of the story but not to the point where the book sounds fake.

Despite its somewhat cheap and cheesy writing style, Steve Alpert's “Sharing a House with the Never-ending Man” is a very interesting and insightful business memoir that educates the readers on the other aspect of making animated features in Japan, that of having to sell them to people from other markets. As such, it is a worthy read not only for fans of Studio Ghibli but also for all film buffs.