Enduring a laborious monotony for a purgatorial lifetime used to be confined to the annals of myths and legends, etched into the pages of stories where men endeavoured rolling boulders up mountains before rolling back down and starting all over again. Since the rising of the industrial sun such an existence no longer enjoys the pleasantries of ancient fictions, instead carving into our largely hegemonic lifestyle like a knife through bone, the blood of its involuntary practitioners smeared into the food we eat, the clothes we don, and the technology we enjoy. The days of the week, the weeks of the month, melt into a lucid stream of consciousness broken up not by the act of rest but by its promise. Yet, as all too many have become aware this millennium, this is a half-truth for only a tiny fraction of those eking out their time; piercing the sumptuous monochromatic symmetry of Hirobumi Watanabe's “Cry” is the sonic equivalent of torment, of frantic boredom, of a life trapped in a cage – and it is deafening.

Cry is screening at Camera Japan

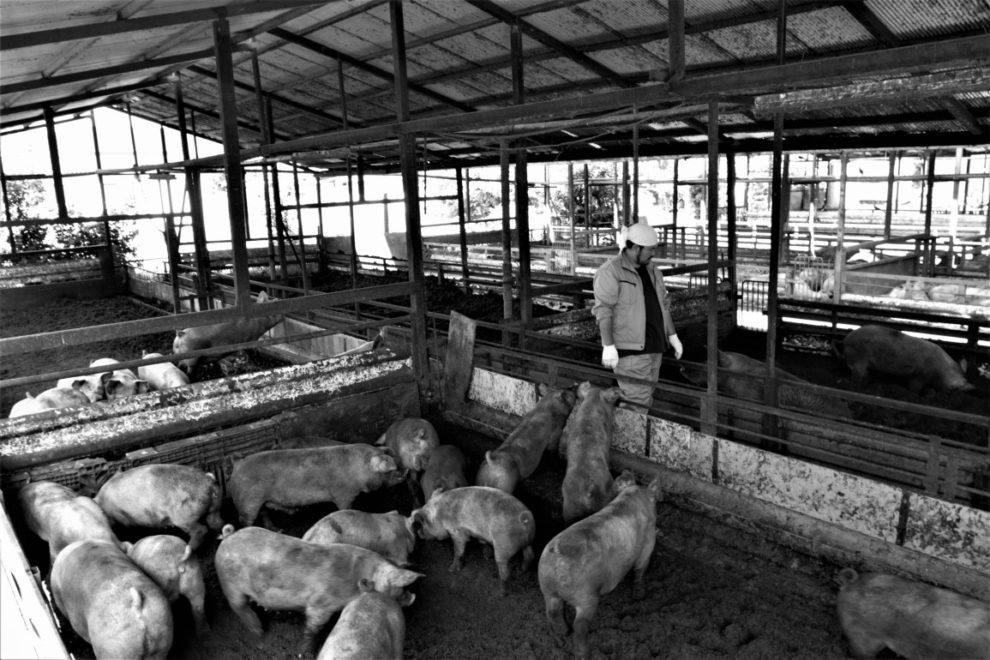

Following any given week of any year in the life of a pig farmer (played by Watanabe himself) “Cry” loses itself in the habitual repetition its subjects slog through, routines only broken by changes in the weather and the Sabbath, as cyclical as the seasons themselves. It is a routine of sleep, work, break, more work, eat, and repeat – as regular as clockwork and as mundane as the life portrayed sounds. With nary a moment without his back to us, Watanabe's farmer progresses through each stage of his day not so much with precision but with an inward focus almost isolated from the world outside his bubble, preoccupied more with the task (and the moment) at hand than what lies down the road. Sharing his spaces are his dishevelled grandmother who only appears onscreen for meals, and the pigs under his ‘care'; they are fed, mucked out, and watered down in tiny enclosures but otherwise left to their own devices. Just as the certain ennui fills the screen visually the shrill of the pigs' unnatural cries uncomfortably envelopes the auditory space to such a nauseating degree all attention on them (no matter where the camera points) never flounders.

As much of a documentary of the minutiae of a simple existence as it is a fictitious examination of man's near detachment from purpose (or, perhaps just a slow film about a week in the life of a pig farmer), “Cry” neither shies away from its philosophy of choice nor preach it with brazen intellectualism. Instead Watanabe, as he so often does, strikes the perfect chord between the two extremes, allowing his audience to bask in the film's contemplation. Following carefully edited sequences we're slowly immersed into his lead's world, meditating on every shot, and left bewildered at the choices he has made: implementing very few changes in his daily routine, Watanabe's farmer freely lives a near solitary existence, fleeting from one moment to the next, and appears genuinely unphased. Meanwhile, as innocent bystanders, we are subjected to the harrowing cries of his livestock in a heightened sensory overload, embellishing the cruelty of a live void of free will, kept purely as a resource; this all culminates to a distressing sequence on Saturday, as the pigs seemingly try to escape but are physically unable to move, as if crushed by the weight of their own hopelessness. It is a sequence powerful enough to make even the hardiest of omnivores questing their diet.

Watanabe frames his enframed subjects with such astounding symmetry that it is impossible to consider this work purely as a probing indictment of farming practice. From his walks to and from work and even on the job, the farmer is shot elevated above the cultivated and the herded, a position of self-assumed power that cannot be unseen but, as is too often the case, is taken as privilege. The composition is striking and undoubtfully beautiful, but then again Watanabe has spent his career perfecting this. A master of mise-en-scène, each frame reflects the void that is lived in, the familiar which is all-consuming, the vast distance between any social interaction. What little attachment to the world outside the current moment – all related to the arts – is only flirted at on screen but the sense of a tenuous connection hits home hard, as seen in his nightly ritual where a book is read every night. Such moments provide a sense of hope but the same is not conveyed on the farm; here is a realm lost to stagnation, an aching domain where care is rudimentary at best. All of this soulfully captured within the confines of the screen.

No mention of this film should come to pass without forgetting to bring up the poeticism of the sound and complete lack of dialogue. “Cry” is a film where no words are needed but that does not mean this is a purely visual masterpiece: As previously mentioned, the titular cries comprise the only comprehensible diagetic communication and these puncture like spears, leaving wounds we must patch up ourselves. Such sounds rip us straight from the photographic splendour, thrusting us headfirst into the pit – from one world to the next. With such precision and poise, Watanabe elevates this universe into the hyperreal, straddling that line between fact and fiction until cross-eyed, leaving us rattled to the core and unnerved beyond all belief.

Leaving the film just as it loops back to the beginning, we are granted a luxury the farmer can never ascertain: escape. Even on his day of rest there is seldom time for enjoyment, drained from a life of work he sleeps in a movie theatre, unbeknownst of the second attendee sat behind him, unaware of any other inhabitants staggering by as the week commences for more of the same; his eyes shut, one must wonder what dreams he is chasing. Meanwhile, we as an audience move on to the next phase, continuing with our own lives, free from the shackles of Sisyphus' myth. At times, “Cry” feels like a dream itself, one which leaves its mark embedded in our souls for a lifetime. We might carry on, but the story will live on in us forever. This is the inherent beauty cinema strives for, and Watanabe has certainly left his indelible mark etched into our bones.