by Luke Georgiades

Every once in a while, a movie comes along with a surrounding legend that is just as interesting and awe-inspiring as the movie itself. “Die Bad” is one such movie. A true behind the scenes underdog story for the independent filmmakers of the world, Korean director Ryoo Seung-wan's overlooked but essential debut is a testament to the moving image and its ability to change lives.

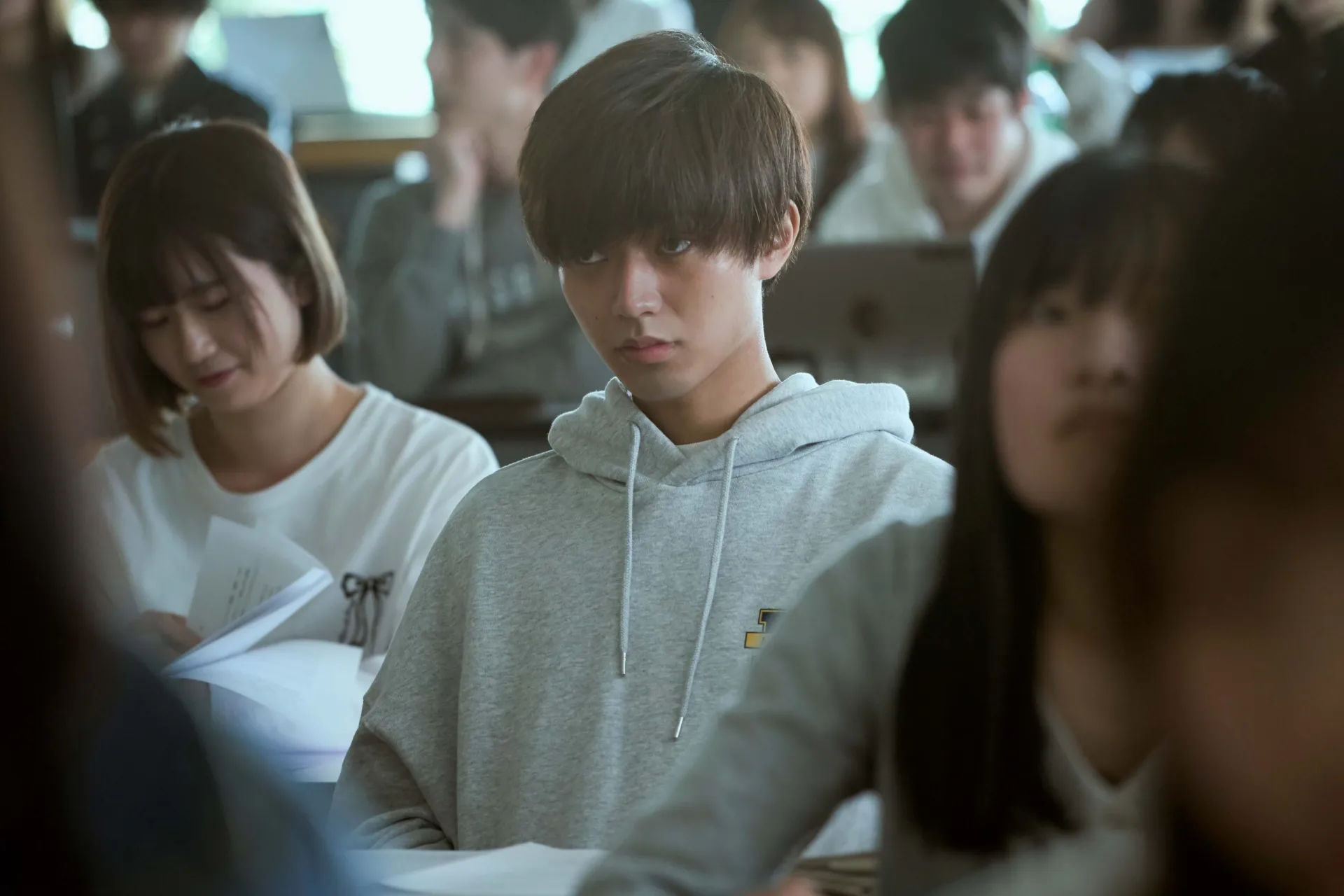

“Die Bad” follows the story of youth's moral corruption across four vignettes entitled “Rumble”, “Nightmare”, “Modern Man”, and finally, “Die Bad.” The premise is as follows: Sung-bin and Suk-hwan are two tech students shooting pool and playing Tekken (mis-branded to this reviewer's itching annoyance as ‘Street Fighter') at their busted-up local clubhouse, when they are challenged to a fight by art students from a competing school. In the ensuing brawl, Sung-bin accidentally delivers a brutal blow that kills one of the art students, and sends a devastated Sung-bin to prison. Released on parole years later, Sung-bin, still haunted by the sins of his past, attempts to live his life on the straight and narrow, but,after catching the attention of a local mob boss, succumbs to criminal life once again. Meanwhile, Suk-hwan has become a respectable and long-standing member of the police force. Aligning themselves with opposite sides of the law, the two former friends' inch closer and closer to an inevitable stand-off.

More than just a film, “Die Bad” is Ryoo Seung-wan's fight or flight response to facing a life in poverty. In an interview with cine21, Seung-wan stated “I bet all I had in my 27 years of life on that film.” And he's not exaggerating. Losing his parents at a young age, Seung-wan spent much of his early years as a middle-school dropout, working odd jobs to provide for his struggling family. Still, dreaming of a future in moviemaking and refusing to settle for a life of mere survival, he took on multiple jobs to pay tuition at a part-time film workshop. Eventually, after several years proving his worth working as assistant director for mentor Park Chan-wook, and gaining substantial buzz for his submission to the 1998 Busan Short Film Festival (“Rumble”, which would later form the first quarter of “Die Bad”), Seung-wan was offered a golden ticket: 50 million won – AKA around 44,000 US Dollars – AKA absolute pittance in movie budget terms – to make his debut feature. Thus, “Die Bad” was born.

Much like Tarantino's iconic Kill Bill duology (and hell, most of his other films.), “Die Bad” is a film that has everything and nothing to do with cinema.On the surface, it's a tale of friendship lost that's been told a hundred times before.Yet, It's the boldness of Seung-wan's execution that separates “Die Bad” from the pack. And bold it is. As aforementioned, Seung-wan was all too aware of the pressure involved with making a debut feature, pressure he quite literally could not afford to crack under. Knowing that he only had one chance to prove himself as a filmmaker, he was struck with divine revelation: rather than creating a martial arts film, gangster flick, horror, or documentary, why not make a film that would demonstrate his proficiency in the sensibilities and stylings of all four, and then some?

In its hybridity of traditional genres of filmmaking, “Die Bad” essentially becomes a radical independent cinematic experiment, steeped with love for the artform and dipped headfirst by the ankle in a pool of homages.Each vignette carries a distinct personality: “Nightmare” is aptly titled, using horror influenced jump-scares and eerie musical cues to bringback to life the haunting spectre of Sung-bin's past. Meanwhile, “Modern Man” intercuts a comically long one-on-one martial arts bust-up between Suk-hwan and gang lord ‘President Kim' with documentary style interviews set minutes before their encounter. It's a genuinely empathetic segment that cleverly juxtaposes two men from different worlds brutally beating each other with the same men accidentally exposing just how similar they are, and how tragically futile this all really is.

It's to Seung-wan's credit as a director that amidst a firestorm of different styles, the narrative and core message of “Die Bad” isn't lost in genre translation. Between the adrenaline pumping, hair-raising action is a clear, emotionally impactful indictment of a harsh and uncaring society that doesn't give its young men a fighting chance.

In true independent moviemaking fashion, Seung-wan's helming of the “Die Bad” is not limited to simply barking orders from the comfort of a director's chair. This is hands-on filmmaking in more ways than one; as well as directing and writing the screenplay himself, he also co-stars and even single-handedly choreographs the action scenes. This wouldn't be so commendable if not for the fact that the action scenes in “Die Bad” are overflowing with the character and rip-roaring excitement created and perfected by the golden age martial arts stylings of Bruce Lee and Jackie Chan – of which Seung-wan is clearly an obsessive fan. The titular segment, “Die Bad”, a thirty-to-forty-man black and white battle royale that brings the film to its bloody end, is executed with a technical ability that shouldn't look so easily achievable on such a low budget, and is truly a sight to behold.

As Suk-hwan, Seung-wan delivers a fine supporting role, but it's Park Seong-bin's stellar performance as the morally conflicted protagonist/antagonist of the same name that carries “Die Bad's” narrative forward.

This is by no means a perfect film. The low production value is glaring, each segment's abrasive style changes are occasionally disorienting, and the difference in quality between 16mm and 35mm has never been so obvious (Due to budgetary restraints, Seung-wan resorted to filming with leftover 16mm rolls from other productions). Seung-wan directs like a man with everything to prove, and only one chance to prove it, not simply dipping his toe in genre territory, but diving all the way in until he can touch the floor. This means that on rare occasion the characters submit to cliché and caricature that threatens to cheapen an otherwise well written dramatic exchange; in one scene, it seemed a strong possibility that Sung-bin would break down into maniacal anime villain laugher (thankfully, wiser heads prevailed and even in a film as batty as this, restraint was used).

However, like a book that's been read to weariness or a roll of film cursed with a light leak, there's a charm here that thrives in the roughness of its edges. A cinematic labour of love that deserves a special place in the pantheon of iconic independent film, “Die Bad” captures the essence of what making movies is all about.