The second book of Kanae Minato, after “Confessions” to be translated in English and the second to be transferred in cinema (both mini series and a movie actually), “Penance” shares some similarities with its multi-awarded predecessor, but strays in completely different paths, for the most part.

“Penance” is streaming on MUBI

15 years ago, Emily, an elementary school student from a rich family transferred to the small town of Ueda, and soon became close friends with four other girls, Sae, Maki, Akiko and Yuka. The girls always played together, occasionally in each other's house, but at one point, after a series of antique dolls were stolen from each of the girl's houses, they experienced a true tragedy. An unknown man came to their school after- hours, while they were playing at the courtyard, and posing as a ventilation technician, took Emily away from the rest, supposedly to help him. A bit later, though, the girls went inside the gym only to find their friend dead and the man nowhere to be found. The incident had a chilling effect on the whole of the local society, but most of all, to the four girls and Emily's mother, Asako. The latter, some months later, invited the girls to her house, only to accuse them of lying about not remembering the face of the perpetrator, and even demanding some kind of penance for him getting away. 15 years later, the lives of every girl are in shambles, with the impact of the murder and Asako's behaviour essentially dictating their actions, although in different ways.

The novel unfolds the stories of both what happened before, during and immediately after the crime in the lives of the four girls and Asako, and the way their lives continued after that, through five chapters, one for each of the women.

Buy This Title

Somewhere here is where the best asset of the novel lies, with the way Minato manages to analyze and individualize all her characters, while gradually bringing all the stories together through the murder of Emily, being truly ingenious. The crimes involved keep the book entertaining from beginning to end, but it is the way the analysis of the characters leads to a number of sociophilosophical comments that make the context so captivating. In that regard, the individual confessions approach works quite well, once more for Minato.

Sae's chapter comments on the place of women in the still quite conservative Japanese society, with the whole concept of matchmaking and the perversion deriving from her husband and his obsession with dolls moving into this direction in metaphoric fashion. Maki's chapter deals with the concept of courage and how society is eager to construct both heroes and villains/”losers” in the blink of an eye. The way families can shape their children is highlighted in Akiko's chapter, which also deals with the concept of hikikomori, and in the harshest way, with child molesting. Yuka's chapter is a bit different, as she emerges as much a victim as a perpetrator, although the almost permanent criticizing of the concept of family is also presented here.

Asako's chapter is even more different, as the one concluding the main story but also shedding light in the cases of the rest. However, the occurrences that take place here are somewhat far-fetched, with too many extreme coincidences and deus-ex-machina tropes, which somewhat detract from the overall realism that characterizes the rest of the stories. At the same time, this is the only chapter that presents the perspective of the parent, in some ways justifying Asako's behaviour after the death of her daughter. Furthermore, one of the most interesting comments in the novel appears here, of how intensely different the relationship of a mother with a daughter and a son is. Lastly, the differences of the “people of the city” and the “villagers” are also highlighted here, with Minato presenting them as bordering on racism.

The concepts of guilt and trauma and the way they can shape people and particularly children are the ones that surround the whole narrative, with Minato making a harsh but also realistic comment about the thin line that separates victims and perpetrators, and essentially, how the latter are created.

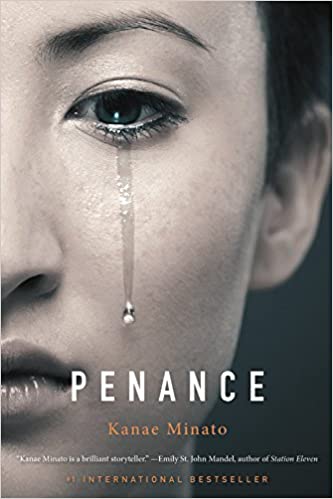

Minato's writing is simple, to the point, and mostly consisting of short sentences, which allow the book to flow quite easily, despite the heaviness of its themes. At 227 pages (Mulholland Books edition), the novel definitely does not overextend its welcome, and it is easy to say that is completely stripped of any unnecessary elements of misplaced beautification. Also of note is the excellent cover of the edition.

“Penance” is on a lower level than “Confessions” but is still an excellent book that works quite well as both a crime thriller and a family drama.