Nisan Dağ graduated from Columbia University’s MFA Film Program in 2013 as a Fulbright scholar, upon which she co-directed her feature debut “Across the Sea” (2014). The film won a number of international awards, among them the Jury and Audience awards at Slamdance Film Festival and Best Director at Milano International Film Festival. A year after, while shooting a documentary about the rappers from Istanbul’s slums for MTV’s Rebel Music documentary series, she got inspired to write a script based on people and milieu she got acquainted with not only during the filming, but also through the intense involvement with the community’s life through the workshops she gave afterwards.

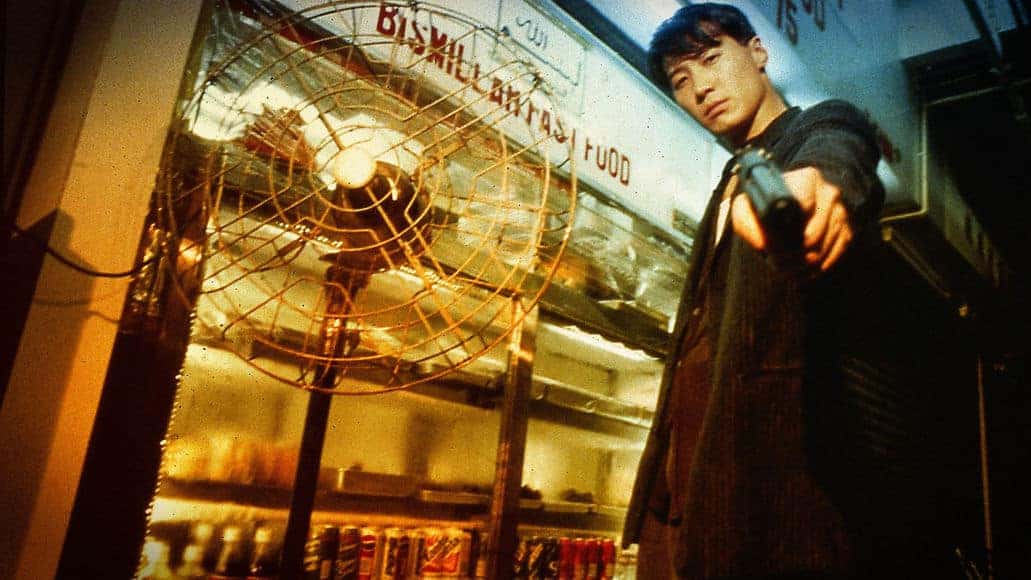

What came out if it is a powerful drama “When I’m Done Dying” which competes in the Official selection of PÖFF (Tallinn Black Nights). We spoke to the director about her inspiration for the film, about shooting in the slum and bonding with both people and the rap music.

You got the idea about the film through a documentary you directed for MTV. Can you tell us something more about it?

The documentary was actually called “The Flowers of Gezi Park” and it was following different characters from Turkey who are activists, and who have drawn inspiration from the Genzi park protests. One of my characters was a rapper form a slum in Istanbul. Additionally, upon finishing the documentary, I volunteered in a children’s workshop, so I’ve spent quite some time in the neighborhood. That led to the writing of the script.

Did you already have a personal connection to the rap scene prior to “When I’m Done Dying”?

It was a process. I was introduced to this world that I did not know of before by shooting the documentary. This slum literally looked like Bronx. And because it’s a very religious neighborhood, you don’t expect to see those cool graffiti. At the beginning, I found it only interesting, so I was more connected out of curiosity. But after spending some time in the neighborhood, I started creating bonds with people there. I started caring about those kids who attended the workshop. At first I was feeling sorry for the troubles they have in life, about the poverty and their parents not supporting them or that they were forced into crime or drug, but then I realized that there was nothing to feel sorry about because they are admirably strong. Also, thanks to the passion for rap music. That inspired me, because as a filmmaker, I feel passionate about telling stories. They take motivation to keep going from the music and rap is the outlet for them to express themselves, especially in the minorities where they are not given the chance to speak up about their issues. That is how I got started with rap which I was not listening to that much before. In Turkey, rap is mostly political and more personal – talking about life. We don’t have such thing as girls in bikinis washing cars, which is something I really like.

You are also addressing the problem of drug addiction to a cheap, dangerous drug.

I met some students who were addicted to this deadly drug called bonsai. It’s a terrible drug. It is very cheap. I think that there is a similar drug in the UK called Spice. It’s extremely synthetic, made out of dangerous chemicals, and it’s incredibly widespread. Thousands of people have died of it. It’s mostly popular in poor neighbourhoods where minorities live, and sometimes I feel like the Government is not fixing the drug problem because it’s “stabilizing” the society. And rap is doing the opposite – people speak up. I saw people being affected by bonsai and their lives are going in a bad direction. I wanted to make a movie to inspire people to hold on to their passion, because I think that the film overall tells them to hold on to their passion.

You shot the movie in an actual slum. How was the actual process of filming?

I shot the film in a slum, which wasn’t the same that the documentary took the place in, because I wanted to protect the real-life characters, my students. The thing is – they all are suffering from prejudice and they don’t want to be labelled as junkies. That’s why I wanted to make it a fictional slum that’s not pointing fingers at anyone. I could have taken another real slum, but that would have been the same problem. I created a universal one that could represent just any similar one in Turkey, especially in Istanbul. There are Kurdish neighbourhoods, the Roma ones, and this could be any of them.

It was interesting filming there, but also very dangerous. We had an encounter with the mafia, although it was funny too. People in such areas are very warm and interactive. There were some memorable moments. For instance, we had a trailer for the toilets and the little kids in the slum were always using them which made the actors pissed off because they always had such a short time for breaks. But I thought that it was actually a nice experience.

There was actually a huge Syrian population in that slum. There were three-year-old kids walking barefoot on the streets picking up broken glass from the ground. No mothers were around. One day, when our American producer Jessica came to the set and this mother came with her two-months-old baby and just put her in her lap. The baby just sat there for a couple of hours. In this type of hoods there is a special kind of warmth within its borders and space. I didn’t include the Syrian context into the film, although it was very tempting for me as a filmmaker. Sometimes we want to talk about everything we can, but I had to resist the urge to stay true to the heart of the story. There are already so many other elements in the film, so even though it was hard to avoid and ignore them and point the camera somewhere else, I hope that I made the right choice.

Did you have some particular people in mind when you were writing the script?

I didn’t think of actors while writing , but after I casted them all, only then I started adapting the dialogues with them in mind in terms of whatever fits them more naturally and what corresponds their nature.

You brought night life very close to the audience. Did you know about those places from before?

I’ll tell you something bizarre. The club scene was shot in the historic water cistern (more like a dungeon) from the Ottoman Empire. It’s not regulated by the government but by the mafia in the neighbourhood, so we needed to pay them for this historical site. With fog and lights, we transformed the place into a club, because we do not have anything like it in Turkey at all. When I was in residency in Berlin just to research the electronic scene for Devin’s character, I went to the nightclub “Tresor” and I was inspired by that space. When I saw the dungeon, I decided to create the club there. Some of the locations that I filmed the documentary in, the city wall, for instance – I used them for shooting as well. This wall is also from the Byzantine times, and it guarded Constantinople. I find it amazing that now it serves as the romantic spot for couples to kiss, but the kids also love to smoke marijuana there, which is actually kind of dangerous. For instance, during the shooting of the documentary we received news that one of our protagonist’s friends have fallen of the wall because he was high, and he died in the hospital. What was also interesting for me, and at the same time a shock was that when I announced we were going to stop filming that day because their friend died, they just wanted to keep going because for them, death is not that tragic, it’s a part of life and it happens very often. In our culture, if someone dies, it’s a catastrophe, especially if it’s unnatural death, but for them it was normal.