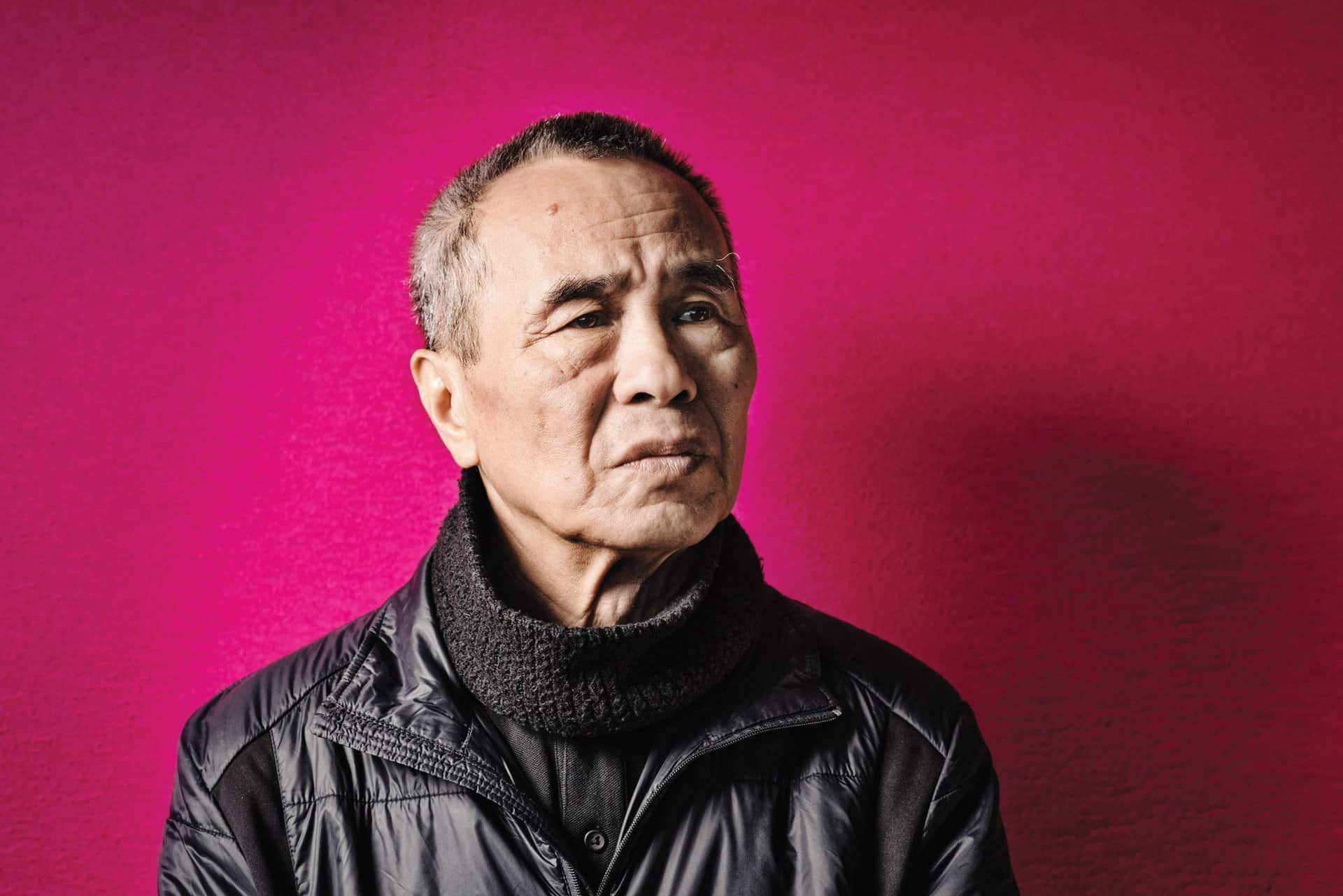

Living between Japan and Myanmar, Akio Fujimoto was born in 1988 in Osaka, Japan. After his college graduation where he studied family psychology, he enrolled in the Visual Arts Academy Osaka to study filmmaking. He worked as chief of the selection committee for the student film category at the Nara International Film Festival. In 2013, he completed his first short, “Psychedelic Family”, a subtly crafted piece based on his own experiences. After graduating, he moved to Tokyo to work on his first feature, a Japan-Myanmar co-production “Passage of Life“, which took five years to complete. The film focuses on a Burmese family living in Japan who gets split between the two countries. His second feature “Along the Sea” brings into light again the invisible communities in Japan. Between these two features, he also shot “Bleached Bones Avenue“, a short film focusing on the Zomi people.

Kazutaka Watanabe is a producer who has produced all of Akio Fujimoto's films and Kenichi Ugana's “Ganguro Gals Riot”, through his production company E.x.N K.K.

On the occasion of “Along the Sea” screening at Tokyo International Film Festival, we speak with them about the lives of immigrants in the film, the research and the cinematic approach that led to the documentary-like realist of the film, the co-production between Japan and Vietnam, the Japanese movie industry and many other topics.

How did this co-production between Japan and Vietnam came to be?

Akio Fujimoto: First, we were thinking of having a story of a Vietnamese woman in Japan, so we thought that we would need some help from the Vietnamese film industry.

Kazutaka Watanabe: With “Passage of Life”, we had the chance to attend Cambodia International Film Festival. I went there and I met an American producer living in Vietnam, Josh Levy, who had established a company with a local director, “Ever Rolling Films”. He really loved “Passage of Life” and so, when we decided to shoot “Along the Sea” I called him and asked for his help. Eventually, he and his colleague Nguyen Le Hang joined as producers and that way, we managed to do an audition to cast three Vietnamese actresses. Me, Akio and DP Kentaro Kishi attended auditions in Hanoi and Ho Chi Minh, and we saw over 100 candidates

The presentation of the lives of the Vietnamese immigrants in Japan is very realistic, almost documentary-like. What kind of research did you do for the film?

Akio Fujimoto: Thank you for saying it is realistic. One big factor is that my wife is Burmese, and thus an immigrant. We recently got a child actually. I have been observing my wife in her daily life having many difficulties coping with the Japanese community, going to the hospital or the City Hall for example. Thus, I am very close to the main theme of the movie, of the difficulties foreign people living in Japan face. Furthermore, dealing with immigrants is my life-work, and I always read the articles I see about these cases and collect information, in my daily life. Therefore, I already had the base of the information about the topic.

Then I went to specific people who had experienced this technical training referred to in the film, and we had interviews with them. They had many episodes to share so I received a large amount of information. However, the film refers to universal experiences, like the one I described about hospitals, and thus the main topic is not culture-oriented. I talked with the actresses about their backgrounds and personality, then took in many things in the character they act. This is the procedure that led to the realism you referred to, and also the fact that the story is pretty simple.

Did you also manage to meet with the people who forge papers for immigrants, as the one present in the movie?

Fujimoto: I did some research bit I did not meet them. At some point, we were thinking of ordering a fake ID to use as props but if we bought one, we would be doing something illegal and we could get arrested.

Can you give us some more details about this whole technical training concept?

Watanabe: First of all, it is a national system, it is not company-driven. The government gives certifications to the organizations that register the program, which are those that match the potential trainees to the company in need of foreign laborers. They use a system that also involves some partners in Vietnam, who “collect” many Vietnamese who initially attend a language school, then they train in different technical jobs, and when there is a matching job in Japan, they are transferred here and work for three years. In the technical trainee system, they did not have the right to choose the company they work for and they could not change jobs after they started working for a company, which was very tough for them. Also, when they enter the system, some of them borrow money, sometimes more than a million yen, and pay the broker or the organization to come to Japan, therefore they actually start with a debt. It is like that in most of the cases, which creates many problems for them.

Is there any chance for them to stay permanently in Japan?

Watanabe: They need to go back, and then find the right opportunity to return to Japan, and if they manage to stay for 10 years, they can apply for a permanent residency. Most of them are not thinking of staying in Japan permanently, however.

Japanese population is aging rapidly, so the need for foreign labor is more intense now than ever. Do you think that this will force the Japanese government to relax her immigrant policy?

Watanabe: Akio and I share the same opinion on this. There is no reason to keep the borders closed; we need foreign labor as the population is declining every year. For a long time, Japan did not accept foreigners as laborers, even through this technical training system; they just accepted them in order to teach them some kind of skill and then send them back to their country. The Japanese ideology suggests that giving these skills allows foreigners to contribute to their country. There is also another level, that is officially accepting foreign labor, because Japan started accepting “Specified Skill Workers” from 2019, laborers accepted in certain fields. This system also has many problems and needs changes and adjustments. May people who employ and help these foreign people, are always asking the government to improve the system, and in a way, that allows them to work safely and make a proper living. We think that this system will change even more in the near future.

Fujimoto: The many bad episodes that take place in Japan for foreign laborers are now spread in the news all over Asia, and as the system is recognized as one with many problems, Japan does not retain a good image in that regard. Therefore, I am afraid that even when Japan opens its borders more, maybe only those people who really like the country would come, many will just decline.

Regarding the episode in the hospital in the movie, would they have helped Phuong if it were a real emergency?

Fujimoto: We also talked about that with the doctors, and they said that they would help if it was an emergency, but after that, they would need to identify who the patients are. If they are illegal immigrants, they would have to deal with the police or immigration office and maybe even get deported after they were released from the hospital.

When Phuong finally is admitted in the hospital, the doctor tells her that she will have to pay a significant amount to continue getting treatment. Is that the case only with foreigners or with Japanese also?

Watanabe: It is the case for both, everyone needs to pay, but you may receive support from the local government.

In the episode where Phuong drops the fish, the attitude of her employer is quite harsh, to the point that it made me think that he was more respectful of the fish than his employees. Is that what you wanted to show with this scene?

Fujimoto: It was not my intention to show that the fisherman is a cruel person or that he is using them. However, some people feel a distance from foreign people, because, actually, most Japanese do not meet many foreigners during their lives. Therefore, some of those local people cannot talk to them in the way they talk to others, and occasionally communicate in the way the fisherman in the movie does.

One point I wanted to make through the cinematic approach in this scene is that the man is on the track while the three women are on the ground, and he is looking down on them. This positioning is actually indicative of how he thinks about them, so maybe that is what gave you this impression.

Watanabe: Btw, the fisherman is Yuki Kitagawa