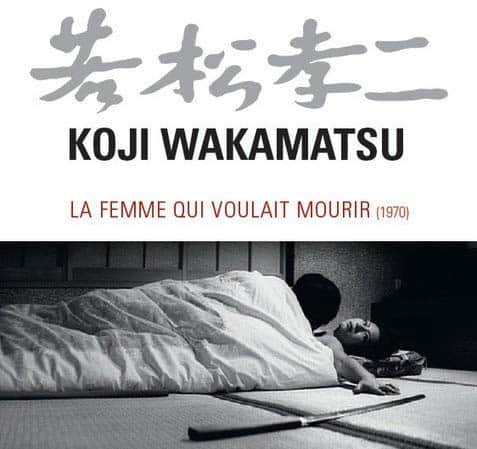

The fact that the pinku film could be used as a medium for both artfulness and sociopolitical commentary has been repeatedly highlighted in Koji Wakamatsu's filmography, and “The Woman Who Wanted to Die” is another testament to the fact.

Buy This Title

Getting inspiration by Mishima's ritual suicide, which essentially failed to fulfill its purpose, Wakamatsu focuses his narrative on two interconnected couples, who eventually meet in a resort during heavy winter, in the wake of the aforementioned incident. The first couple comprises of a mature man and a younger girl, with the former insisting to marry her, despite the fact that she considers herself unworthy and having suicidal tendencies. The second couple comprises of a rather angry young man, who is about to commit suicide due to his anger for his girlfriend abandoning him, and the owner of the resort, who, in her effort to calm him down, ends up having sex with him. Soon, it is revealed that the first man once attempted a failed suicide with the second woman, leaving her a grotesque mark with his sword as a souvenir, while the woman who abandoned the young man, is actually the one he is marrying.

Mishima's suicide and the whole concept of harakiri seem to be ridiculed here, as Wakamatsu has his protagonists wishing to kill themselves for rather shallow reasons, with the finale highlighting the comment in the most eloquent fashion. Furthermore, that the woman of the first couple wants to commit seppuku also moves in the same direction, particularly because the ritual is mostly associated with samurai men, with women committing it in very few occasions.

The way footage from the news of Mishima's actions is juxtaposed between the sex scenes, also seems further the comment, while additionally functioning as a rather functionable transition medium for the narrative, which mostly comprises of sequences of almost absurd dialogue (in a fake philosophical package: “we wanted to know how selfish our selfishness was” utters one of the protagonists) and sex scenes. Isamu Nakajima's convincing work in the editing is also highlighted through the succession of these scenes.

The latter, however, highlight Wakamatsu's ability to shoot erotic scenes in a way that is both titillating and artful, with the blurred images and the shooting through the mirror highlighting the fact, as much as Hideo Ito's excellent cinematography. The way the sound is implemented through the women's moans is also great, adding to the sensualism of the scenes, without making them look cheap in any way. The same visual artistry is also exhibited in the exterior shots, with the snowed mountains gaining a lyrical hypostasis through the excellent framing, despite the fact that the film retains its minimalism at all times.

In just 71 minutes and with a large part of the movie being reserved for sex scenes, the fact that Wakamatsu manages to make eloquent comments about both Mishima and suicide as a concept emerges as a true achievement and a testament to the heights he raised the pinku film.